A pale-yellow convertible crawls down an open road. Fists pump in the air, flashes of grey hair billow in the wind. The trio at the core of pioneering rock band Fanny are blasting their first album in decades, hurtling down the highway on a wave of hope.

Fanny: The Right to Rock introduces one of the very first all-female rock bands, one that paved the way for generations to come, yet never quite got its due. While Fanny was active in the 1970s and the members are now in their early 70s, the film pulses with the feeling that their long-deserved recognition is just around the bend.

“The convertible scene was a bit of an ode to Thelma & Louise — women rocking on the road and doing shit their own way,” says director Bobbi Jo Hart. “Fanny doesn’t drive off a cliff, but they’re driving somewhere amazing that remains to be seen.”

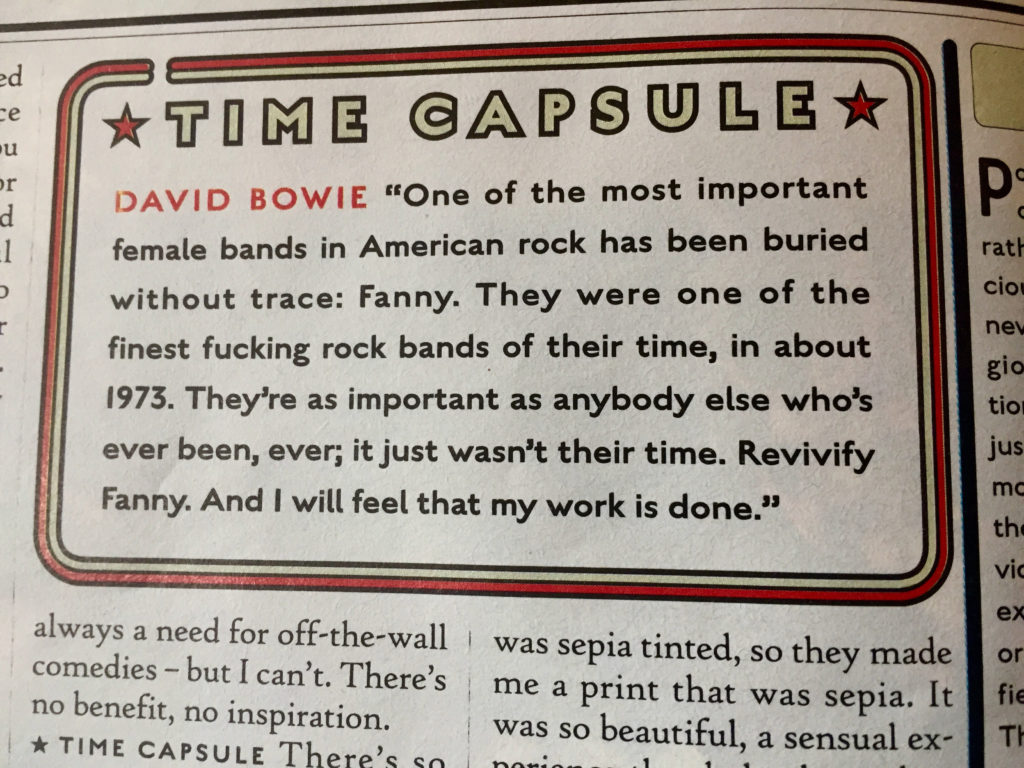

Fulfilling Bowie’s wish

The doc takes David Bowie’s words from a 1999 issue of Rolling Stone as its mantra. “One of the most important female bands in American rock has been buried without a trace: Fanny. … Revivify Fanny. And I will feel that my work is done.”

Hart has risen to the challenge. Despite growing up in California when Fanny hit the scene in the 1970s, she had never heard of the band until a few years ago. The seed was planted when Hart stumbled across a profile of Fanny’s guitarist June Millington while browsing Taylor Guitars’ website, shopping for her daughter.

“I read the story of Fanny and my mouth dropped open,” says Hart. “I was so upset, which was sadly a familiar feeling. I look back after making films for 25 years and I realize that nearly all of my films have been about women, and often about untold stories.”

Hart immediately contacted Millington about the possibility of a documentary, and she and the other bandmates were interested. The idea went to the backburner as Hart wrapped up her work on Rebels on Pointe, a documentary about the boundary-breaking NYC dance troupe Les Ballets Trockadero de Monte Carlo.

The Fanny project was reignited serendipitously at a Madonna performance. Hart was at the Women’s March on Washington watching the show when she spotted Millington on the back of the stage. The two reconnected in DC, and Millington had news to share.

“She said, ‘Guess what? We got a record deal. We’re recording an album.’ It was then that we hit the ground running,” says Hart.

Famous fans and Fanny Hill

To chronicle the story of Fanny was not a straightforward task. The band toed the line between fame and obscurity, and had a winding path with a rotating cast of six members. Now they were releasing their first album in decades.

The complicated timeline of Fanny’s story is untangled with killer editing. Archival footage and photos are woven in and out of recent interviews seamlessly, often set to songs from the band’s new album with impeccable timing. Hart began by filming in the studio as they recorded their upcoming album, Fanny Walked the Earth. The story of Fanny’s legacy and history unfolded from there, as old friends swung by the studio to be featured on the album.

Legendary musicians like Cherie Currie (of the Runaways), Bonnie Raitt, and Kate Pierson (of the B-52s) sing Fanny’s praises in the film, speaking to the doors the band opened for women in rock. Joe Elliott (Def Leppard) digs out his Fanny flexi-disc from when he was twelve years old. Big names are big fans of Fanny, both now and back in the day.

“It was important to the broadcaster that we gather some of these more well-known artists to help contextualize Fanny’s place in it all,” says Hart.

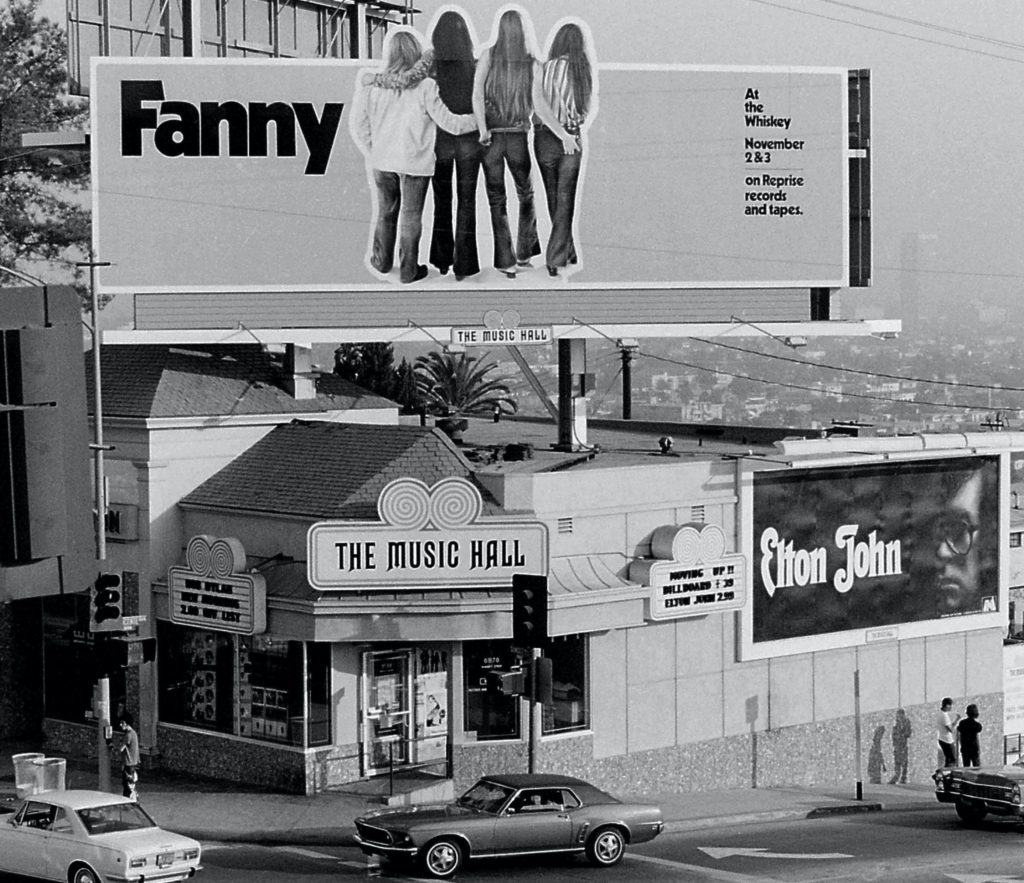

Perhaps one of the most iconic periods in Fanny’s history was their time at Fanny Hill, which Hart recreates in vivid detail with a vast archive of photos. The aptly named house in Los Angeles had a revolving door of rock star visitors, from Joe Cocker to Bob Dylan, who swung by to jam or just hang out.

The photographs and stories from Fanny Hill document an era where it felt like the band was on the cusp of making it big—but ultimately, they didn’t. The doc makes it clear why this was. The audiences, media, and industry of the time couldn’t comprehend the complexities of Fanny.

More than an “all-girl band”

“It was Alice, a drummer of Fanny, who said that the record company didn’t know how to market them,” says Hart. “They were more than just this ‘all-girl band.’”

“Half the band was Filipina-American and half the band was gay. The record label never mentioned it. I never found one article in my research that mentioned that,” says Hart. “It was super important to me to delve deeper and to show the depth and complexities of these human beings, as much as I could in an hour and a half.”

Three of the core members of Fanny as it stands today—June Millington, Jean Millington, and Brie Darling—are Filipina-American. Back in the day, the lesbian bandmates were coached to allude to non-existent boyfriends to brush off inquiring interviewers.

The band is no stranger to sexism, racism, or homophobia, and their new era confronts the inevitable ageism faced by female musicians their age. While Fanny may be surprising some by still walking the earth, they’re the furthest thing from dinosaurs. The band’s energy remains contagious.

“Fanny is a great example of how failure is just a hurdle,” says Hart. “You’ve not succeeded in life without failing an infinite number of times, and I doubt you’re going to find someone who succeeded that did not have to climb or fall over a ton of hurdles along the way.”

Hurdles and turtles

Growing up on food stamps with a single mom struggling to make ends meet, Hart has experienced her fair share of hurdles. She recalls an experience with literal hurdles that impacted her philosophy of life and filmmaking.

Hart was especially good at 300-metre hurdles in high school. She recounts one race where she was in the lead but caught her foot on the third hurdle and faceplanted. She tripped and fell over every last hurdle, crossing the finish line last, embarrassed and bloodied.

“When I got on the bus, the driver handed me this little note,” Hart says. “He’d taken his pen and had drawn a little turtle that was trying to run. He wrote, ‘To Bobbi Jo, for determination in the face of adversity.’ It sounds silly, but it was a beautiful moment for me, because I felt like such failure when I fell.”

Hart’s ability to feel Fanny’s hurdles as her own speaks to her empathetic, highly personal approach to documentary-making. It shows in the film. Fanny: The Right to Rock brings the audience along for the ride as if they were long¬time friends.

“My takeaway from that day, and the takeaway from Fanny and the film, is the same. Determination in the face of adversity,” says Hart.

Fanny’s biggest break could still be on the horizon. As Jean quips in the film, “I tell my friends, maybe I’ll be famous when I’m 80!” Hart is optimistic that, pandemic-willing, the band can be in attendance at a number of festival screenings this year and play some live shows to accompany them.

“What is the definition of success? Did Fanny succeed? “I think they did,” says Hart. “Did they get the recognition for how phenomenally talented they were? No, and maybe that’s still to come.”