IT’S AN INTERESTING COINCIDENCE that 2005, the hundredth anniversary of the first publication of the anti-Semitic fraud The Protocols of the Learned Elders of Zion, saw the infamous tract re-visited and re-examined by two disparate but prominent artists. Will Eisner, the legendary graphic novelist, passed away in January 2005 at age 87 but not before finishing his final work, The Plot: The Secret Story of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, which has since been published by W.W. Norton. And filmmaker Marc Levin’s Protocols of Zion, a personal cinematic journey into the meaning and influence of the book today, made a splash when it premiered at the Sundance Film Festival and is certain to excite more talk when ThinkFilm opens it commercially this fall.

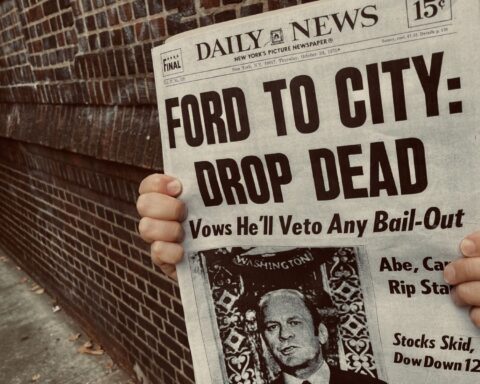

It takes a while for projects to gestate so the fact that both the graphic novel and film came out in the same year shouldn’t be overemphasized. That doesn’t mean, however, that the twin releases are not important. Many may rightfully recognize The Protocols as a discredited forgery but it continues to exert a malign hold in today’s world. Post-9/11 rumours—modern day Protocols, in fact, —that Jews either engineered the terrorist attacks or were conspicuously missing from the Towers, because of prior warnings, continue to circulate, particularly in the Arab and Muslim world, which always equates Jews with Israel. Closer to home, anti-Semitism in Canada has become more prevalent, so much so that a good friend of mine, who isn’t Jewish, regularly reports anti-Semitic utterances that have been made in his presence.

Both Eisner, whom I interviewed in June 2004, at one of his last public appearances at a local comics convention, and Levin, whom I spoke to when he was in town for the film’s Canadian premiere at the 2005 Toronto Jewish Film Festival, had their specific reasons for tackling The Protocols and entirely different approaches to the subject. Eisner’s came out of a lifelong interest and knowledge of Jewish issues—“I write what I know, any writer worth his salt (does that)”—and personal experiences of anti-Semitism in the ’20s and ’30s when he was growing up. Another of his recent graphic novels, Fagin the Jew, dealt with Charles Dickens’ problematic literary character, eliminating the anti-Semitic overtones surrounding his depiction.

“The angle of what I’ve done (in The Plot) is to tell the story of how it probably was written. I felt it necessary to address the public who reads it (years) later,” said Eisner, explaining that the usual debunking of The Protocols is written by academics for scholars and not for the audience he could reach with a so-called comic book. The 40ish Levin’s take on The Protocols, which is that of a much younger, more assimilated and comfortable American Jew, was based on curiosity. “I’ve done a lot of films, dealing with extremists over the years so I had my own personal fascination with what makes these people tick.”

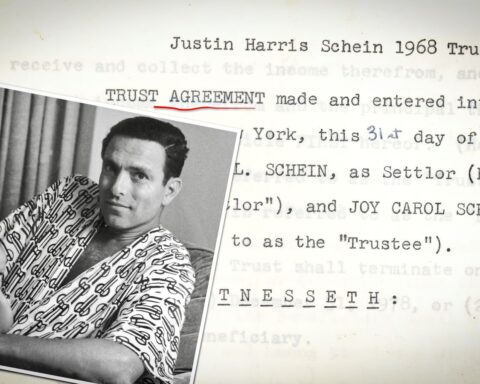

Tonally, the two projects are also very different. Eisner’s book is an incredibly detailed and meticulous examination of the history of The Protocols, which had its genesis in a tract, written by Maurice Joly in 1864, entitled A Dialogue in Hell between Machiavelli and Montesquieu, a thinly disguised diatribe against Napoleon III, that had nothing to do with the Jews. About thirty years later, it was re-worked by Mathieu Golovinski, at the behest of two advisors to Nicholas II, Russia’s last Tsar before the 1917 Revolution. They feared the coming storm and sought something that would turn the Tsar against what they saw as the social changes threatening Russia. Blaming the Jews for the so-called ‘reforms’ and turning the anti-Semitic Nicholas against them was easily accomplished with the publication of The Protocols in 1905. The rest of The Plot tracks the consistent re-emergence in different countries and languages over the years of that foul book, which has been utilized by everyone from tycoon Henry Ford, who printed it in his newspaper, to Adolf Hitler, who cited it in Mein Kampf, to today’s crop of white supremacists and anti-Semites. The Plot is very much a scholarly tome, written (occasionally in a somewhat stilted form) in the usual Eisner style which combines educational pictorial motifs with his spare, cropped dialogue.

Levin tackles The Protocols with barbed humour, and ties it in with 9 /11 and Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ. In one chillingly funny sequence, a paranoid, ranting New Yorker claims all of the city’s Mayors have been Jews. What about the Italian Rudy Giuliani, he’s asked. His answer, that Jewliani’s name gives him away, is unintentionally hilarious. There’s also an amusing moment surrounding the movie’s pivotal incident, which got Levin started on the idea for the film in the first place, when an Egyptian cabbie in New York insisted to Levin that the existence of The Protocols was fact. What’s not in the film is Levin’s own sarcastic retort, to the effect that he knew that because his great-great-grandfather was at the meeting. He omitted the answer because “I had to be careful. At first I thought I needed to do a kind of shtick, (to give the film) entertainment value.”

Levin, whose films include Brooklyn Babylon, a Jewish-Arab love story, Slam, about a poetry spouting hip hop artist and Godfathers and Sons (for Martin Scorsese’s Blues series), felt it necessary to put himself in one of his movies for the first time. The views of his compatriots had a lot to do with that decision. “(They would ask) ‘Marc, why are you doing this? How did you grow up? What’s your family’s story?’ It (the personal angle of the film) was really more about answering those questions, trying to give the film another texture so that you could digest (it). That led me to make it more personal.”

But Levin did not start out to make the film in personal manner, which from this critic’s point of view doesn’t always mesh well with the broader issues the movie raises. “(As for the) personal side, I never thought it would converge as it did (in the film). I just tried to start in a very authentic place,” which for native New Yorker Levin is Ground Zero. By contrast, you don’t sense Eisner in The Plot, even though he puts himself in one panel looking for information on The Protocols in a public library. He could be any scholarly Jew interested in researching the text.

Interspersed with Levin’s personal observations are a number of fascinating scenes with other New Yorkers including a frightening visit with a white supremacist who, despite knowing Levin is Jewish, is open to discussion, because he liked a previous film the director had done on one of his compatriots. Levin’s Protocols of Zion also showcases the worldwide manifestations of anti- Semitism, refracted through the original spurious text. Most startling of all is the footage, talked about in the West but never seen, of a controversial Egyptian TV series based on The Protocols, which ran last year throughout the Arab world during Ramadan.

Levin has recently joined a synagogue for the first time. While his spiritual path was, in part, the natural outcome of a “rediscovery of Judaism,” which actually began before the film, with readings of Jewish history and the Zohar, the rest of his decision did come from making the movie. “It’s strengthened me; it’s connected me to my own people.”

When asked about the film’s tone, which is wry rather than angry, Levin replied that it came out of the film’s timeline; it was begun soon after 9/11. “The rage, or the anger, was more a numbness, of how to make sense of the kind of post 9/11 world and the vulnerability (I felt). I don’t think I could make the film now (in that way). I feel strengthened in that (I made the film) and I feel I have more bearings in this new world.”

Nevertheless, the ugly realities dealt with in Protocols of Zion were also a direct challenge to where Levin, whose parents were activists, came from. “I came of age in the ’60s, (during) the anti- war movement, (and the) civil rights movement. After the Cold War ended, (we felt) we had moved into a more global community so this was such a shock (that) we were kind of in a religious gang war age. We don’t live in a world of peace and love now. There are people who would hate you just because of who you are; they don’t care if you want to talk to them or if you want to reach your hand out (to them) and that’s a frightening reality.”

If one actually wanted proof of Jewish ineffectualness in combating anti-Semitism, a far cry from what The Protocols claim it’s all about, you only need look as far as the scene in Levin’s film which could have been subtitled “The Passion and the Hollywood Jews.” Attempting to elicit opinions on Mel Gibson’s controversial opus, Levin, who found the film to be “boring and one dimensional,” contacted various members of the Hollywood Jewish community. Rob Reiner, Norman Lear, Larry David, to a man, gave him the run around and referred Levin to another of the group for a view of the film, which he never gets. Rabbi Abraham Cooper, Associate Dean of the Los Angeles-based Simon Wiesenthal Center, said about that segment to Levin that “those 45 seconds summed up my 20 years in Hollywood.” The filmmaker didn’t actually think that Jewish power brokers in Hollywood would hesitate to offer their take on the film’s alleged anti-Semitism. “I was surprised but it’s obviously a more sensitive subject than I thought it would be in this day and age.” So like the old anti-Semitic canards that Jews are both communists and capitalists, clannish and infiltrators, one can add another, all-powerful and very cowardly. In many ways, The Passion incident puts the lie to all the racists’ charges of Jewish omnipotence.

That brings us to the reasons The Protocols and other racist texts need to still be discussed and examined. When asked why he felt it necessary to address Dickens’ ethnic stereotyping in Oliver Twist by creating Fagin the Jew, Eisner said, “It hit me, this was all wrong and it needed to be addressed. It also opened up a new opportunity for me, a new direction for my work,” which led to his last book, The Plot.

We won’t know where Eisner’s work would have gone next and Levin’s future steps have yet to be taken but clearly The Protocols have spoken to them both. The least we, in the often oblivious West, can do is listen to what they have to say. Or we can, like the Hollywood Jews, hide our heads in the sand and pretend nothing is happening. That, however, as The Plot and Protocols of Zion make clear, won’t make anti-Semitism go away.