The past year marked the 40th anniversary of the Iranian Hostage Crisis in which 52 Americans were held captive for 444 days beginning on November 4, 1979. The event receives a timely retelling in Barbara Kopple’s Desert One, a riveting documentary about an ill-fated Eagle Claw rescue mission that attempted to bring the hostages home. It’s one of Kopple’s strongest films yet in a prolific career that includes two Oscar wins (for Harlan County, USA and American Dream) and a roster of films that have deconstructed the American psyche in terms of free speech (Shut Up and Sing), migration (New Homeland), and consumerism (My Generation), just to name a few.

Kopple, speaking with POV during the 2019 Toronto International Film Festival where Desert One had its world premiere in September, vividly recalls the experience of being gripped by the headlines as the story unfolded. Making the film and speaking about it with fellow doc enthusiasts, she praises President Jimmy Carter’s ability to be cool under pressure and speak diplomatically at even the worst moments—an effect that makes the experience of watching Desert One in 2020 doubly prescient. Even when the mission hits snag upon snag—disasters include a helicopter explosion and an additional hostage situation when a busload of Iranian villagers crosses paths with the mission—Carter responds politely and cordially in the audio recordings that Kopple presents. Her interview with the former President gives audiences a model for true leadership as Carter humbly recalls a tragic turn in an event that defined his presidency.

It’s also a departure for a filmmaker whose oeuvre generally consists cinema verité and profile documentaries. Hollywood’s takes on the Iranian Hostage Crisis, as thrilling as they are, don’t have the same depth and breadth of research. The scope of Desert One is what ultimately makes the saga so exhilarating as Kopple assembles all the players involved and uses a range of archival footage, new interviews, and audio recordings in which Carter receives updates about the mission in real time, while animated sequences fill in the gaps left by the covert mission. The film reminds audiences of America at its best at a time when the President had the courage to fight for the safety and security of his citizens. Desert One, to paraphrase one interviewee in the film, is all about having the guts to try.

POV caught up with Kopple at the Toronto International Film Festival in September to discuss Desert One, interviewing President Carter, and a career in documentary.

POV: Pat Mullen

BK: Barbara Kopple

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

POV: What was it like as a young person in America during the Iranian Hostage Crisis?

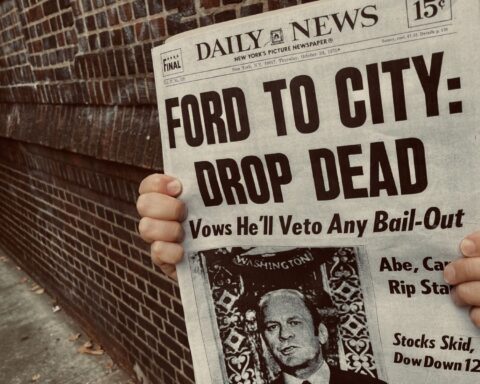

BK: I’d finished Harlan County around that time and when Jimmy Carter was President, I felt that there was a lot of hope in terms of what was happening in the world. When the hostages were taken, it became very frightening and scary and very difficult for Jimmy Carter. There was a small window when life felt so good and I felt so safe, but then it turned another corner and off we were into Reaganland.

POV: The audio recordings of the phone calls with Jimmy Carter are extraordinary. What impression did of President Carter did you get from them?

BK: I think it was probably really painful for Jimmy Carter because at the beginning [of the mission], everything was going well and then suddenly, Murphy’s Law, everything that could possibly deconstruct, deconstructed. There’s a part in the audio recording where you just hear him breathe on the tape. [Kopple pauses and re-enacts the dramatic tension as Carter receives news about a fire on the aircraft that killed several soldiers.] I just felt that he was coming apart and that it really hurt.

POV: How was the experience of interviewing President Carter?

BK: It took a long time to get permission to interview him. Phil Wise, at the Carter Center, would never call me back until I started having a relationship with his voicemail. He finally called me and he said, “Okay, but you’re only going to get 20 minutes. Come on February 14th.” I was excited and it was Valentine’s Day, so I got a little box of chocolates for the President. I had been in South Sudan filming with Kate Taylor, who’s James Taylor’s sister, and teaching the women how to bead, so I brought a little red heart for the First Lady. I didn’t personally give them the presents because they said any chatter would come off my 20 minutes. But I didn’t really get 20 minutes! I got 19 minutes and 47 seconds. It’s all right. I was happy.

POV: It seems like a much longer interview given the range of emotions Carter displays, so what was the challenge of hitting those notes with less than 20 minutes?

BK: I really had to think about what I wanted and what I didn’t know. A friend of mine said that Jimmy Carter is very straightforward and that he’s not emotional. He said, ‘Barbara, don’t think you’re going to get anything that’s emotional.’ I asked if we should have a dinner bet and he said, ‘Done.’

I really just started talking to Jimmy Carter about this situation, what it meant to him, and how he felt to let news of it come out. I did get a lot of emotional material. Particularly when he said that his father had died and he never thought anything would hurt as much as that, then losing these men and having these men also as hostages was as painful as anything he’d ever gone through. [Although President Carter cries in the film, Kopple has yet to receive her dinner.]

POV: What is your strategy for interviews? What do you do if a subject is sticking to the script?

BK: I see an interview more as a conversation. I don’t stay on script. I let them lead me. I research and I have questions, but I’m willing to throw them all away to see which corner they’re going to go around. They might say things that I would never think of in my wildest dreams that they would say. It’s much more fun to do one-on-one and see where it goes.

POV: How was the process of relieving this experience with the Desert One survivors?

BK: Many people said, “No, we’ve lived it. We’ve gone through it. We don’t want to talk about it anymore.” But there were an awful lot who said yes. They really looked forward to telling their stories. Like, Roland Guidry [a U.S. Air Force commanding officer from the mission] who talked about when the British soldiers brought the Americans the case of Bass Ale. He talked about taking the piece of cardboard piece from the case where they wrote, “Thank you from all of us for having the guts to try.” When I called him to tell him about the film festival and inviting him to come, he was so excited. He said this was the first time in 40 years he could tell his story like this. He said, “I’ve been interviewed a lot and this is the first time anybody has ever completed anything.” It made me feel good that I was giving him something to show that his time wasn’t wasted and that his feelings and his experience counted.

POV: The balance with Iranian perspectives is very effective too. How did you track people down to tell that side of the story?

BK: It was very important to me to tell the full story. I never leave a stone unturned and it wouldn’t have been a real story if it was just the American side. We had to understand what the Iranians were feeling about the Shah. This was a person who they felt had done terrible things to the Iranian people.

We had an Iranian crew of two women. We were vetted by the revolutionary guard. They told the guard what we were doing, and they said yes. They did a little research and these interviewees were some of the people that the revolutionary guard picked for us to talk to who had been involved. But [Mahmoud Abedini] was luck because they went to the village [nearby the Desert One mission site] and they asked if anybody had been part of it. The villagers said that there was a man who was 11 when he was on the bus that encountered the mission, and that he still lived nearby. It was just by luck that we got him in. I think that’s one of the most interesting pieces in the film because you hear how he thought like a kid. He was so excited about getting back and telling his friends about his adventure.

POV: How do you choose your subjects, whether they’re A-list names or everyday people?

BK: You could name somebody’s name and their story could be fascinating, right? You don’t wake up and say, “Oh, I have to do a film on this or this.” Somebody can call you up and say, “How would you like to this film?” and suddenly a new world opens. For the Woody Allen film Wild Man Blues, a friend of mine called me from Chicago and said, “How would you like to film Woody and his jazz band?” It was spectacular to be able to do that.

POV: I revisited that film when you were the Hot Docs honouree in 2018 and I’m surprised it hasn’t come up more in recent years as a window into Allen’s relationship with Soon-Yi. The film affords her a lot of agency that the press usually doesn’t.

BK: When I did that film, they weren’t married and people asked why I was going to do it. I said I wouldn’t miss doing that film. We make assumptions. We like to stereotype people, put them in corners, and hurt people. I hope I’m not one of those people. I want to know who someone is, see what a relationship is all about, and how people deal with each other, so those concerns don’t affect me.

With Soon-Yi, the camera was rolling and she was wonderful. She had this game where she called Woody out. He wanted to stay at home in the hotel or have a delicious dinner and read or write. She would say, “I want to go out. I want to see Bologna. I want to see Paris. I want to see all these places. We are going to a fashion show.” It was a film about youth and age and keeping each other going. When Woody talks to you, he’ll talk to the head person. Even though my crew would be there, he would just talk to me. If he talked to the jazz band, he talked to Eddy [Davis] even though everybody else was there. Soon-Yi would say, “Why are you doing that? They’re all standing there. You can talk to all of them. Do you ever say thank you to them?” The relationship between the two of them, whether they were going swimming or going on the treadmill, was an equal relationship. Each one brought their own strengths to it.

POV: Some of your films are portraits of individuals but others, like Desert One, are collective. Do you have a preference?

BK: Even though it seems like a chorus of characters, each one says a certain reflection that’s picked up by another, by another, and by another. Together, they have a relatively seamless piece that takes you on a journey.

.

POV: What’s it like creating a film about an event for which you might have material that surrounded the incident, but nothing of the action itself due to the covert nature of the mission?

BK: We had fun. We got to work with an animator [Zartosht Soltani]. Francisco Bello, the writer/editor, and myself figured out all the places where the animation might be. The animator was great and he did pencil sketches and graphics. The producers would be in charge of making sure it’s the right plane and it would hit at a certain angle so that everything was historically correct. It was challenging, but challenging in a great way when it started to come alive. Deborah Wallach, who did the sound design, was fantastic finding pieces of sound to connect everything. I wanted you to feel like you were there and that the film was just unfolding in front of you, that you weren’t just seeing archival and talking heads. I wanted people on the edge of their chairs seeing what was happening and going through what these guys were experiencing.

POV: Did Argo come up much during production? How do you feel that film portrayed the Hostage Crisis?

BK: Oh, I loved Argo. I saw it so many times before I knew I was doing this film. It was great and gave you that sense of fear. When I started doing the film, I noticed that [Ben Affleck] really made sure that the actors looked like some of the hostages. For one of the hostages in Argo, the actor looked like the real John Limbert [who appears in Desert One] with the glasses on and the dark hair. Argo was wonderful. I loved it.

POV: How was it telling another side of the story? A generation of people probably know the Iranian Hostage Crisis mostly through the context of Argo. If you told them about a rescue mission, they’d probably think of Tony Mendez and the Hollywood caper.

BK: This film will take them another step further. Not only were the Canadians involved, but there a lot of guys who didn’t get out. At the beginning of Argo, you see that some of them escaped, but there were all those people that were left inside the embassy. Now people will learn about this mission. Argo was one wonderful pocket in one story, but there’s also a larger story to be told.

POV: How did making dramas like Havoc inform your documentary work?

BK: I see my documentary process as informing my dramatic work. One of the first ones I did, the series Homicide: Life on the Street, was with Tom Fontana. The episode was called “The Documentary” and it had all the different characters in it. They usually just follow two characters and this one followed all of them, so it was supposedly much harder. Yaphet Kotto said, “I don’t have a lot of lines to do, so I’m gonna go back to my honey wagon and relax.” I said, “No, these are all your guys and these are their stories and you’re in charge of them all. When we put the camera on you when you’re looking at it all, that’s the money shot.” I couldn’t believe I said that, but I said that to him. Andre Braugher was doing another scene and said, “You’re a documentary filmmaker, so that means we only do one take.” I replied, “A documentary filmmaker stays there until she gets everything, and that could be all night.” Making documentary made me unafraid. It made me able to express myself with actors and have a lot of fun.

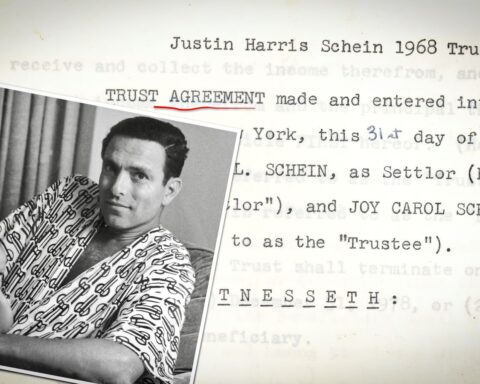

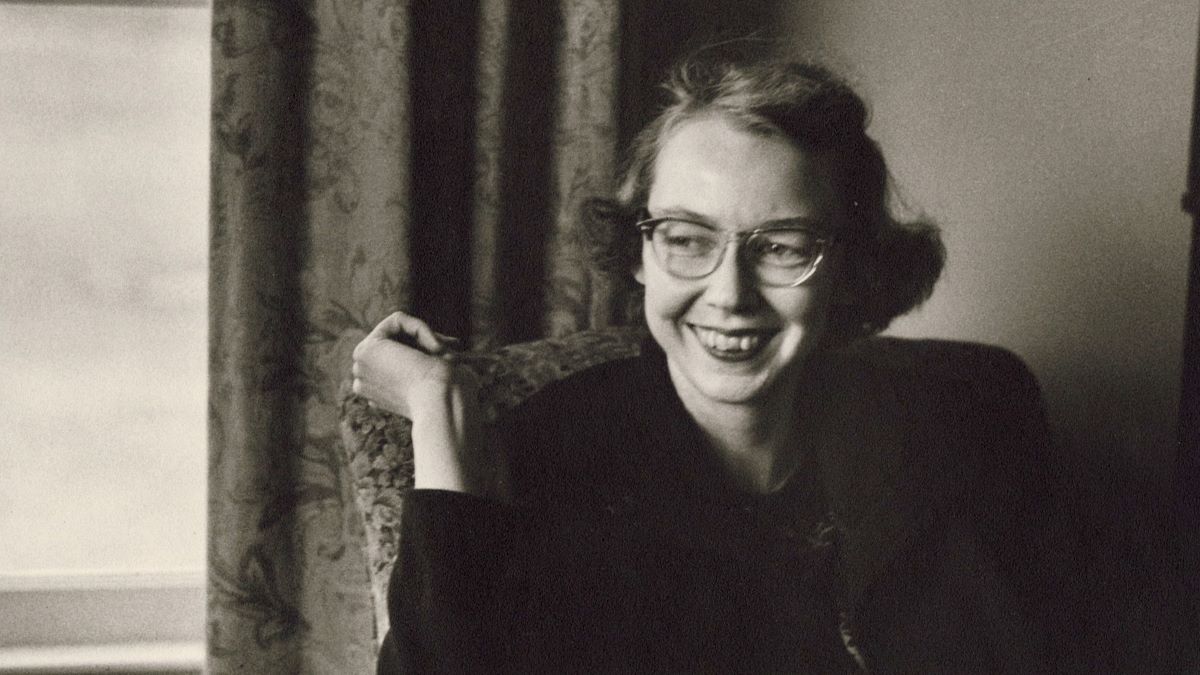

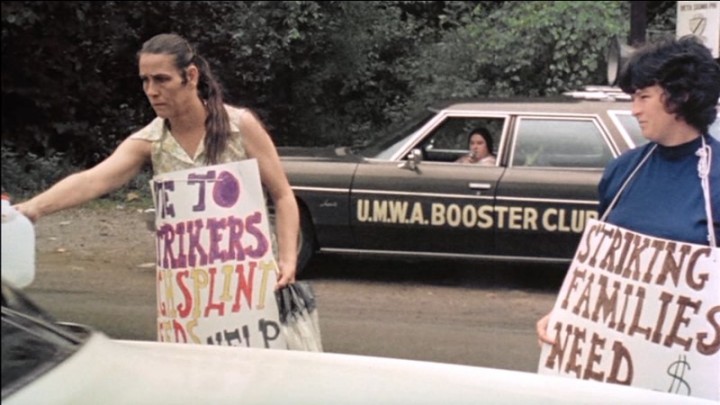

POV: Will you ever get sick of talking about Harlan County? It was a big hit early in your career [1976] and it still plays here all the time.

BK: I love Harlan County. It was one of the first films I did by myself. It taught me so much about life and death. It introduced me to people that I’ll never forget as long as I live. Sudie Crusenberry, the character who said, “I’m not after man, I’m after a contract,” passed away and her daughter called and asked if I could say her eulogy. Harlan County was a movie where we really trusted each other. For a film like that, you make such an intimate relationship that it’s hard to let it go. It’s very much a part of who I am.

POV: Desert One is a great story of heroes, so who are some of the people who have helped you along the way?

BK: Bruce Springsteen helped me with American Dream. We had no money whatsoever and doing American Dream was hard because it was like 60° below with the wind chill factor and [the meat packers] would strike outside. I came into the union hall after filming, and my office called on the phone and they said, “Barbara, you have $250 left in the bank. What are you going to do about it?” I got into bed—I’d been up since three in the morning outside filming. I wrote to Bruce and said, “You have three options. You can give me a lump sum of money, you can let me have a small percentage of one of your concerts, or not.” I never heard anything after that until the office called again and I said to the people in the union home, “I’m not going to take it. I know what it’s about and I don’t have anything to say.” They said, “No, no. You have to.” I got on the phone and the office said we got $25,000 from Bruce Springsteen.

POV: The film features a number of dedications, including the late actor Rip Torn. May I ask more about your relationship with him?

BK: We did The Bearding of the President [1969] together. It was a film that Rip wanted to do. He also did a tiny voiceover in Harlan County. “We’ve got our guns now!” was his line. He was a really great friend of mine. When we did The Bearding of the President, he had his Nixon nose and he would quote Shakespeare [from Richard III], “March on, march on, since we are up in arms / If not to fight with foreign enemies / Yet to beat down these rebels here at home” referencing people who were demonstrating. I think there’s one print of the film. His son Tony found it in his closet when he passed away. I was with Rip the night he got the information that his father died. He was always a good friend.

POV: The other dedication, D.A. Pennebaker, might be more obvious as a connection with his mentorship, but what were some of the ways that he influenced your career?

BK: From Penne, I learned about curiosity and generosity. What he did for me was very special. When I was doing Harlan County, I felt somewhat alone while making it. I asked Penne if I could screen the film at his office, just in front of people that he knew. He invited all these people that I totally looked up to like Charlotte Zwerin, Susan Steinberg, and different editors. He took a chance on a young unknown filmmaker and took the risk to show my work to all his friends. We’ve been friends ever since and I adore his wife Chris [Hegedus] and they’ve gone to every single one of my films. We always talk so much about life and film and everything. We were really good friends. Losing him is really hard, but to have him in my life was amazing.

Desert One premiered at the 2019 Toronto International Film Festival and opens in select theatres August 21.

It opens virtually at Hot Docs Ted Rogers Cinema August 28.