Barri Cohen is a key figure in the Canadian documentary community. An award-winning producer, director and writer, she has honed her skills over years, contributing to television series and documentary shorts and features. Barri is one of the co-founders of Hot Docs and is a past chair of DOC (Documentary Organization of Canada). She has worked tirelessly for decades, enabling and mentoring filmmakers in the non-fiction field.

I have known Barri for over 30 years and am proud to be her colleague and friend. We have worked together on POV Magazine for decades; her contributions as a publisher and editor are crucial to this magazine’s existence.

POV can’t review Barri’s film Unloved, which premieres at Hot Docs. I will, having declared my prejudice in favour of her work, still state that it is a fine documentary in the classic tradition of films that advocate for the disempowered while passionately showing what happens when impersonal governmental forces harm those they should protect. To find out more about her film, please check out the website and read Barri’s filmmaker diary in POV issue #116.

While not reviewing her film, it is my pleasure to interview Barri Cohen on her latest documentary feature.—Marc Glassman

BC: Barri Cohen

POV: Marc Glassman

POV: Unloved is a personal story for you, Barri, since your two half-brothers were sent away as small children to live at the Huronia Regional Centre for intellectually disabled children and youth, the subject of your documentary. But it’s not just personal—it’s as much an investigation of what happened there to so many people over the years. Can you tell me about how the investigation process began for you?

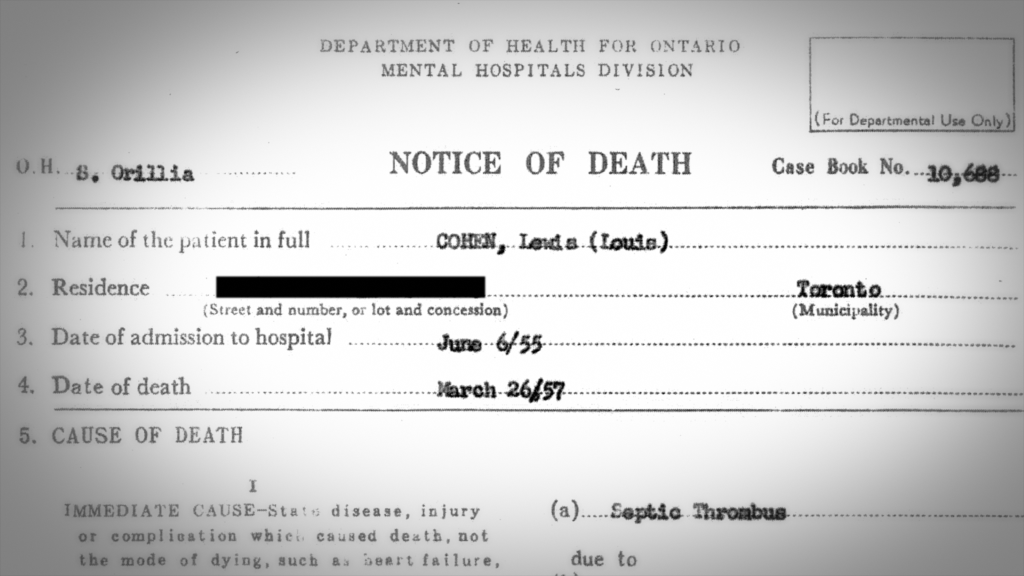

BC: In December 2013, I got a call from my half-sister Adele. My dad had two families, from two marriages. Adele is my half-sister from his first marriage in the early 1950s. I knew Adele as someone my brother Marshall and I grew up with, we saw her a lot, but I never met her brothers Alfred and Louis. My dad always said Louis died at home at the age of two. He was so severely neurologically compromised, he claimed, that his organs couldn’t support him and he died. I never asked where he was buried. I just thought, ‘that’s terrible’ and just didn’t think about it.

BC: In December 2013, I got a call from my half-sister Adele. My dad had two families, from two marriages. Adele is my half-sister from his first marriage in the early 1950s. I knew Adele as someone my brother Marshall and I grew up with, we saw her a lot, but I never met her brothers Alfred and Louis. My dad always said Louis died at home at the age of two. He was so severely neurologically compromised, he claimed, that his organs couldn’t support him and he died. I never asked where he was buried. I just thought, ‘that’s terrible’ and just didn’t think about it.

When Adele called me that December, she asked ‘are we getting any compensation?’ There was a class action lawsuit against Ontario that just had been settled because of Huronia Regional Centre’s abuses and harms. Adele’s call was during the week that Premier Kathleen Wynne had stood up in the Ontario legislature to apologize to survivors of the three institutions. [POV note: the other two institutions were the Rideau Centre in Smiths Falls and the Southwestern Centre in Chatham-Kent]. There had already been a class action settlement with survivors of the three places and they were going to get over $30 million. So I asked Adele, ‘why would we get money?’ She said, ‘that’s where Alfie died.’ It was news to me. I started doing research at that point, not knowing about Louis. I found out who the lawyers were, and they had a really good website with lots of research and information on it, plus a statement of claim from the two plaintiffs (survivors Marie Slark and Patricia Seth).

I read through it and was absolutely stunned. It reminded me a lot about what we had heard from Indigenous residential school survivors. I just had a sense that nobody knew about this in my own community, in the province of Ontario, let alone Canada. And I started reading whatever documents that had been made public that could gave me a bird’s eye view into the sordid history of Huronia. It turned out to be a place that was very similar to many across North America. I was shocked by the claims and the range of neglect, abuse and harm. And I was chilled by the idea that for my half-brother, who according to my father was non-verbal, it must have been awful and terrifying for him to have endured that place with no access to conventional speech–to defend himself or speak up in any way.

I talked to my older brother Marshall about what I’d discovered and told him, ‘I think I need to make a film about this. What do you know about Louis and Alfred?’ Marshall said, ‘Louis died at home but I don’t know where he is buried. I do remember being a pallbearer for Alfred.’ In the meanwhile I reached out to Marilyn Dolmage and her husband, Jim, who were the litigation guardians for the lawsuit and they were gathering people together to share stories and memories. They were the centre around which information was being funneled about next steps after the settlement.

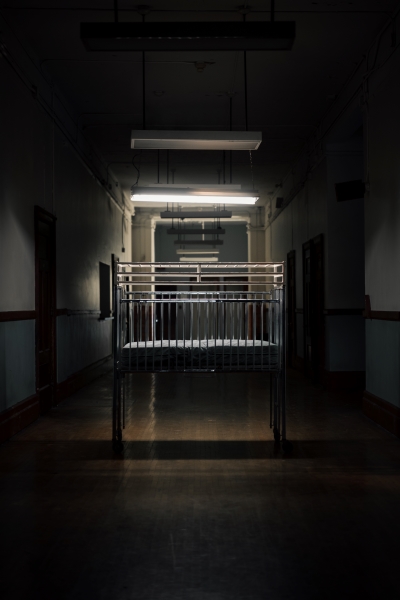

One piece of the settlement was that people connected to Huronia, either as a survivor or family member, could go to Orillia and tour these empty buildings. I told Adele, ‘I want to do this film, but I won’t do it unless you give me permission.’ She said, “Absolutely—do it!’ I said, ‘it could be difficult for all of us, especially you.’ And she said, ‘I know, but I’ve always wanted to find out what happened.’ So in the summer of 2014, we went on several of these tours of Huronia.

POV: Did you decide to film right away?

BC: Yes, I bought a little Canon HD camera and started shooting right away. I’m always nervous about being kicked out of places but Marilyn Dolmage said, ‘come along.’ When you see Adele walk up the steps at Huronia, that’s my first impressions. We could never get back in to film the place substantively, so about 90% of that footage of the inside is my own work.

Throughout that summer of ‘14. I started writing up proposals, and as I was trying to get the film funded, I discovered that Louis had not died at home, but had actually been in Huronia as well, sent there as a two-year-old. Meanwhile, Marshall got on the phone with the ministry in charge of birth and death certificates, and they had no record of Louis’s death. Adele seemed to think that he was probably at the same cemetery as Alfred, but that place had no record of him. It was part and parcel of how children were treated as nothing.

Since he was at Huronia, at least I could get his patient records, leaving a trail of what happened to him after he died, but that went cold. Still, these records are fulsome in a way; you do get a certain narrative.

POV: What is revealed through the archives?

BC: Quite a lot. There’s a new website, Recounting Huronia’s Archive, which analyzes many records and documents to understand what took place there. It has been developed through Professor Kate Rossiter at Wilfrid Laurier University and a team of academics and community activists, some of whom are in the film.

POV: What did you glean from the files?

BC: This is patient record material from the 1950s, so they remind you of what Michel Foucault wrote about in Madness and Civilization and Birth of the Clinic. It’s all very structural and orderly, with the surveillance of bodies for the benefit of those in power. There’s nothing much about the boys as people, as human beings with human needs for comfort, love, or play but you do get their heights, their weight changes, what they ate, what their toilet routines were like. And of course you get their apparent IQ’s with disastrously demeaning labels of ‘idiot, moron, imbecile,’ which were classifications used since the early 20th century.

Yet we know from Alfred’s file, on intake, that he could say ‘mama,’ and they never built on that with speech pathology. Once they made their determination that he was an ‘idiot,’ there’s no evidence in the file that there was any attempt at supporting his growth. What you get is a very flat medical discourse, with maybe a bit about temperament initially, but then it’s never really remarked on again. There’s a biomedical history, but you don’t really get a social life narrative Like what did Alfred do all day? Did he play with other children? Did he have toys? It only comes in near the end of his life in the early 1970s.

There is an indication in a note that went home to my father, that he had a hematoma. We don’t know why because it’s redacted in the file. When I spoke to the ministry (Community and Social Service), I asked, ‘do you redact staff information?’ They said, ‘if it involved a patient who may have beaten up your brother, then they would’ve redacted that name, but not staff.’ I have to take them at their word.

I didn’t really get a chance to get into this in the film, but the staff was so poorly trained. Many were returning war Vets, with their own PTSD quite possibly. They were bored out of their minds. They would encourage the patients to be jealous and do violent, awful things to each other, sadistic things, and beat each other up. They treated these children as objects to play with, abuse and humiliate.

POV: How did you feel, as a person, making this film?

BC: One of the things about making a documentary is it allows me to distance myself from what I’m discovering. For the longest time, I was just focused on finding out what happened. I felt intellectually driven. Maybe because I was telling this story, I felt angry. When I think about my dad and the secret he kept, I was amazed. I wasn’t mad at my father. I was sad that he felt he had to keep it a secret. I come at a lot of this story, even though some of it is about my family, from a point of curiosity and I take delight in being curious. I had a certain amazement about discovering Huronia. So when I discovered the truth about something that my father took to his grave, I thought, ‘here’s someone I believed had no secrets. But he did.’ It shattered an image I had of my father.

I was amazed that my father kept from us, what happened to his son Louis, where he went, how he died and where he was buried. Even my father’s sister didn’t know. I don’t know if his own mother, who was an observant Jew, knew. It’s hard for me to imagine even now that she would allow a grandson to be buried without Kaddish [the traditional mourning prayer], without a gravestone and memorial after a year. Then I thought about the forces at play culturally and historically and personally for my father that would’ve conditioned him to make that secret possible.

POV: What you’ve talked about, Barri, is deeply powerful. But you decided to not make the film just about your family. Unloved is about so many others, victims and survivors of the abusive environment at Huronia. Can you tell me about your decision to do that?

BC: Quite frankly, I always knew that the family story was just going to form just one set of threads in a larger tapestry. The stories of Louis and Alfred would inevitably connect up to living testimony from the survivors and former staff people, including those who rose above it like Marilyn Dolmage and Debbie Vernon [who worked in those toxic environments and now address that legacy]. The living memory and testimony of survivors informs us all of us about what it was like there. It’s through the survivors we can experience where they lived, and how they coped with being separated from their own families and what they could never speak about until the class action and now.

POV: When did you start to meet survivors and figure out who should represent them in the film?

BC: On the very first tour of Huronia, I met two of the key survivors, the core class litigant-survivors, Pat (Patricia) Seth and Marie Slark, both of whom were there by the age of 7. Marilyn and Jim Dolmage were on the tour that weekend, too. They were the litigation guardians for the lawsuit. That’s when I heard Marilyn’s story and it resonated personally with what I knew about Alfred. Marilyn not only was a former Huronia staff member, but she had also suffered the loss of a brother (Robert) who was sent away as a toddler, about the same time as my brothers. There was this gap in her life always because of Robert’s absence and the secrecy in her family about him. I realized that the film should try to encompass not just the pain of being there, but of separation as well. Marilyn put it well to me, “I was the sister always waiting for my brother to come home.”

Marilyn was the first person I asked to join the project. She agreed and told me that there was an academic community who were going to be writing books, doing survivor involved art projects, and creating websites now that the settlement had happened. Through her, I kind of embedded myself with the survivors of Huronia and the community around them, like Remember Every Name and Debbie Vernon’s work with the group’s members and its founders like survivors Harold Dougall and Cindy Scott. It’s an advocacy group created to acknowledge those who lived at Huronia and are buried at its cemetery.

Marilyn was the first person I asked to join the project. She agreed and told me that there was an academic community who were going to be writing books, doing survivor involved art projects, and creating websites now that the settlement had happened. Through her, I kind of embedded myself with the survivors of Huronia and the community around them, like Remember Every Name and Debbie Vernon’s work with the group’s members and its founders like survivors Harold Dougall and Cindy Scott. It’s an advocacy group created to acknowledge those who lived at Huronia and are buried at its cemetery.

It all happened organically. I got to meet many survivors on the Huronia tours, and got a chance to ask questions, build trust, and get their permission on camera to tell their story with the intention of making the film.

POV: Can you talk a bit more about how the patients were treated at Huronia?

BC: A core theme I discovered while researching the film, is the link between sadism and care when “care” and “residency” are industrialized. Realizing that was a game changer for me. What is it about us that makes us angry and almost sadistic when tasked, under specific conditions, for caring for our most vulnerable in society? Professor Kate Rossiter from Wilfrid Laurier in the film talks about the conditions that lead to that. There are failures in oversight, accountability, failures in care models that don’t prioritize human values, such as keeping families together. And we don’t prioritize how to create communities for humans to lovingly support others who need us. It’s a huge underlying issue that we have to address, now, because as our society ages, we’re more interdependent than ever. Co-litigant Marie Slark, one of the survivors, once said to me, ‘where you will be when you get older is where many of us have already been and are now. You will need support and care, too.’

POV: How did you get Unloved financed?

BC: I pitched it to key players in the doc commissioning field including the NFB, CBC and TVO. Nobody really bit until The doc Channel. I met with Jordana Ross when I was producing Toxic Beauty and Jordana got it immediately. In fact, what really excited her was the universal themes and problems I just mentioned around “care,” and she could see that Huronia was part of a larger systemic failure and history, that we have to continually address (in Long Term Care and in the acknowledgement of dehumanization with Indian Residential School legacy).

POV: Please tell me more about the making of the film.

BC: You know, the famous question, ‘how many times do you make a film? You make it three times–on paper when you’re pitching it, with cameras when you’re shooting it and, finally, when you’re editing it.’

I knew I had to get the masters with my family members and the survivors. And I knew pretty much what the survivors were going to say because I had followed them on various speaking engagements for a long time. I had heard them share their memories and thoughts. Plus I had talked a lot with them over six years. When they shared their patient files with me, that was actually really challenging because I had to judiciously pull key things out to help inform my questions and the larger frame of empathy as well.

The real question of the balance happens in the edit room. In that I was very much inspired by how editor James Yates cut Toxic Beauty with director Phyllis Ellis. Threading various storylines and getting that balance was a real education for me. Phyllis was able to feed certain storylines and then come back to them at key moments, which would inform the following scene. I took these techniques very much to heart. So when it came time to figuring out the balance, I had to think ‘how much information about my family or about one of the survivors is needed at this point? Can we leave that story now and return to it later?’

I knew that the bulk of the film really had to be about the survivors. I wanted the story of my brothers Louis and Alfred to conclude the film, and to tee up the wider chorus of voices. We edited the survivors’ testimonies almost musically as a choir, rather than having a deep dive on any one person per se. Rather, I wanted to thematically organize it so the audience would understand the memories of fear, mistreatment and abuse in a collective way.

POV: At what point did you realize that your emotional conclusion could be centred on burials?

BC: The use of Huronia’s burial ground was an evolution. Initially I didn’t think that it was going play the role that it did although I understood its importance immediately. It was a place of great pain and dehumanization because there are some markers there and a few stones, but primarily there are many, many unmarked graves. [There are some graves with names on them while others are unmarked, depending on the era when the burial took place.] It looks like it could be a mass grave too, but we will never really know. Every Mother’s Day, the Remember Every Name survivor group gathers there to remember the dead and tell stories, sing songs and have some ceremonies, and I filmed these days over five years. When the group got funding through some leftover class action money to commission an artist, Hilary Clark Cole, to sculpt a beautiful monument, I thought that filming it would provide some provisional closure redemption of humanity for survivors and the dead.

One of the promises of the class action settlement, was that the government was supposed to make things right for the victims of Huronia by putting up proper burial markers and creating some kind of monument there. What the government built, instead, insulted survivors, who were never consulted. They never did an unveiling. They never had a ceremony. The government just did it what it wanted to do, and they got it wrong. And so I knew by 2018 that I’d have to underscore that the indignities of deceased Huronia residents buried there, actually followed them to the grave.

By then, if you paid attention to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission and what elders and Indian residential school survivors were saying, you understood that there were unmarked graves of children at those schools. And that’s a common theme: when you remove the humanity from people, you think nothing of robbing them of proper burial. Just like at Huronia and likely many other places. It doesn’t just happen in war, but in subtler forms of eugenic practices and genocides. So I was thinking about all this when I remembered that the Nazis would take Jewish headstones from cemeteries and make roadways out of them. If you convince yourself there’s a category of people who are not fully human, the next step is to justify doing whatever you want with them. Even in death.

POV: The ending is so emotional. Was it something you planned to do?

BC: Yes. I always knew I would open the film with my brother and I going through our half-brothers’ files, and I always knew, whether we ever found evidence of Louis’s burial or not, that I would have a new stone dedicated to both of our brothers and have a Rabbi say Kaddish, and a Cantor sing in Hebrew, Psalm 23 (The Lord is My Shepherd).

Unloved premieres at Hot Docs on May 3.