When An Inconvenient Truth came out in 2006, its style—or you could argue its lack of style—was celebrated for its immediacy and ability to convey hard-hitting facts about the environment. It was a landmark film on climate change that was quickly dubbed “intellectually exhilarating” and “essential viewing.” Its premise was simple: director Davis Guggenheim pointed his camera at politician Al Gore, who, after unsuccessfully campaigning for president, travelled to podiums across the United States to warn Americans about the threats of climate change.

Who can forget Al Gore on stage, backlit by a giant screen with photos and graphs showing damning evidence of rising temperatures and disappearing glaciers? It was before people readily had access to TED Talks on YouTube and audiences couldn’t get enough. Here was a film that spoke clearly to issues that affected the health and well-being of the entire planet in an even faster and more engaging way than Rachel Carson’s seminal book Silent Spring did in 1962. It netted $24 million at the box office in the US alone. To this date it’s the 11th highest-grossing documentary ever.

And it wasn’t just audiences, the response from critics was unilaterally positive. With uncharacteristic fervour, critics were urging audiences to watch the film, not only for themselves, but “for future generations.” Reviewers had little to say about the aesthetics of the film: Certainly, the visuals and the way the film looked was secondary to the message. But much more than observational films and even news-style documentaries, the format proved to be one of the quickest ways of transmitting information to the greatest number of people, especially about a topic that had been too long overlooked. Guggenheim’s method of conveying Gore’s truth proved to be highly influential.

Guggenheim added interstitial pieces to the documentary showing clips of Gore on the campaign trail as well as bits about his upbringing. In truth, the most interesting part of the film, however, is the lecture itself, with its eye-popping images of global warming events from around the world. Well paced and with a few jokes thrown in for good measure, Gore strings together an arsenal of grisly truths into a hard-to-ignore argument in favour of protecting the environment.

If You Love This Planet, Terre Nash, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

It isn’t the first film, however, to incorporate a recorded lecture into a documentary. Canadian director Terre Nash’s NFB film, If You Love this Planet, featuring Helen Caldicott presenting on the consequences of nuclear war, snagged an Oscar in 1982 for best short doc. Similar to An Inconvenient Truth, the film intercut other footage to highlight its message. In this case, it was visuals of the bombing of Hiroshima and burn victims as a way to heighten the urgency of the Australian physician’s message. The film was quickly labelled political propaganda by the Reagan government and was temporarily banned in the United States. Even the CBC initially refused to play the film, claiming it was biased. Of course, the attention only worked to further popularize the film with audiences.

Today, the lecture-style documentary is one you see few filmmakers pitching. Amidst a growing trend of slick documentaries that borrow heavily from fiction filmmaking, the genre is like the Bran Flakes of the non-fiction world. And yet, it’s a style of documentary that has endured— and will likely continue to do so—for its simple yet effective approach.

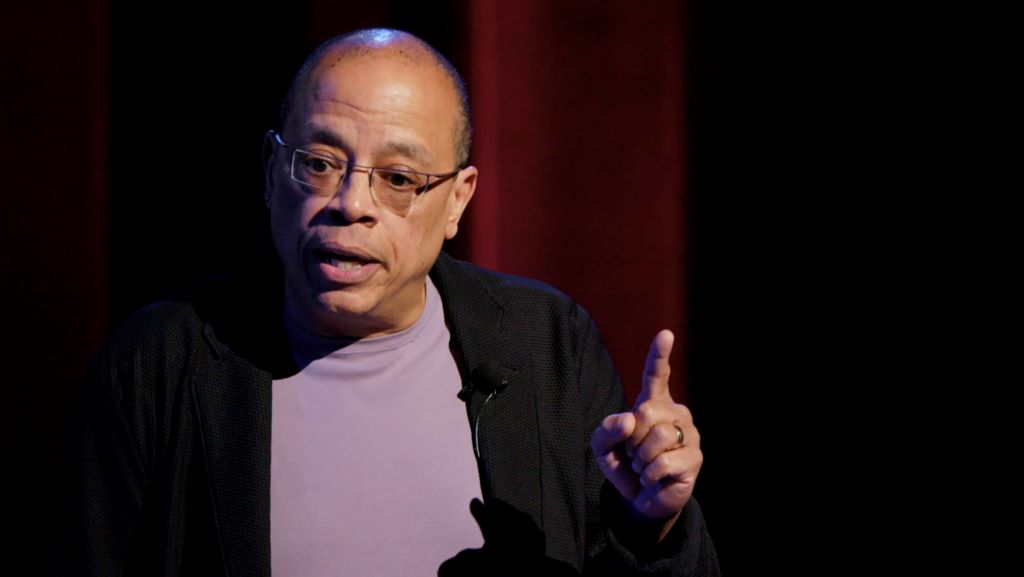

In 2021, filmmakers Emily and Sarah Kunstler released Who We Are: A Chronicle of Racism in America. The film follows former American Civil Liberties Union lawyer Jeffery Robinson as he delivers a ground-breaking argument about how deeply encoded white supremacy is in the United States, and the ongoing oppression of Black Americans. Robinson stands on the stage of the Town Hall Theatre in New York City addressing a large audience. At the front of the stage is a clock where you can see that the lecture actually spans a full three hours.

The film edits down the lecture and inserts footage of Robinson visiting many of the locations he refers to, including Tulsa, Oklahoma; Memphis, Tennessee; and Charleston, South Carolina. It’s an upgraded and more dynamic version of Guggenheim’s film, and it hits hard. By the halfway point of the film, when Robinson is discussing the Tulsa massacre in 1921, it’s impossible to not feel the immensely crushing weight of American history. It’s an example of a documentary that works by removing the focus on characters and storylines and fixating on the accumulation of facts as told through the powerful oration of a man like Robinson.

Honour to Senator Murray Sinclair, Alanis Obomsawin, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

Honour to Senator Murray Sinclair weaves a similarly devastating historical argument, this time in the names of Indigenous, Métis, and Inuit peoples across Canada who were subjected to cultural genocide through the residential school system. Senator Sinclair, in accepting an award from McGill University, takes the opportunity to discuss in convincing detail the many ways in which the First Peoples of Canada were treated as second-class citizens. Directed by legendary Abenaki filmmaker Alanis Obomsawin, the 2021 documentary intercuts the senator’s speech with evocative and heartbreaking stories from residential school survivors who spoke at the Truth and Reconciliation Commission hearings. It’s difficult but essential when Obomsawin includes the testimony of a survivor who was referred to by a number instead of his name, separated from his siblings and abused by the people to whose care he was entrusted.

Obomsawin and the Kunstler sisters do well in weaving in first-person narratives to more powerfully illustrate what’s being said on stage. And yet, the momentum of all these films is still in large part carried by the speakers who lecture as ministers from a pulpit. They’re impassioned and deliver tightly worded arguments that are hard to ignore.

Lecture-style documentaries may have a leg up compared to other documentary genres: The directors know precisely where the lecture is going and that their subject’s magnetism and strong message will hold audiences. As filmmakers, they still need to come in at the end to carefully shape the message and intercut additional footage to make it even more dynamic, but the storyline is clearer than in other documentaries.

Although not the sexiest of formats, the lecture-style documentary is economical and faster to produce than an observational doc, with its clear beginning, middle, and end. And from an information-sharing perspective it also saves the orator from having to perform and re-perform the lecture to a new and different audience each night. It’s no surprise that If You Love This Planet was labelled political propaganda, given its ability to spread its argument so quickly. This is the precise ingredient that makes an otherwise “boring” documentary format successful.

In truth, however, watching the vintage films many years later doesn’t have the same impact or effect as when they were initially released. They’re very much moment-in-time documentaries. As knowledge and technology change, these documentaries remain static snapshots of the point when the lecture took place.

Who could argue that An Inconvenient Truth is more timeless than Grey Gardens (1975) or The Gleaners and I (2000)? After the proliferation of TED Talks on YouTube in the late aughts, the lecture-style documentary became even more pedestrian. Suddenly any savvy speaker with a good idea could get on a stage, hold a PowerPoint clicker, and deliver their message. It might explain why there were so few lecture-style documentaries following An Inconvenient Truth that had the same resonance.

There was a sea change in the 2010s, when documentarians were significantly moving away from reportage-type films. A documentary was a film, not a piece of news, and with the increasing popularity of documentaries in the 21st century there’s a strong desire to differentiate the two. Even Michael Moore, who one could argue is not the most artistically minded documentarian, was purposeful in making this distinction when he spoke to industry delegates at the 2014 Toronto International Film Festival. “If you want to make a political speech, you can join a party, you can hold a rally. If you want to give a sermon, you can go to the seminary, you can be a preacher. If you want to give a lecture, you can be a teacher. But you’ve not chosen any of those professions. You have chosen to be filmmakers and to use the form of cinema. So, make a movie.”

Using Moore’s line of reasoning, a “movie” arguably looks a lot more like fiction than a lecture or a news-style documentary. Filming a speaker behind a podium with images on a screen above them seems almost redundant. With the rise of social media and YouTube, documentaries have had to set themselves apart and capture audiences’ attention. Borrowing story structures, lighting, and camera movements from narrative filmmaking has become so commonplace that not using these elements puts a documentarian at risk of appearing lazy. It’s no surprise then that many documentarians, younger ones in particular, view lecture-style documentaries as being old-school and pretty colourless in form (admittedly I find myself in this category). Audiences want to feel not only challenged by the information and characters presented but by the storytelling and choices the filmmaker makes.

But what’s most interesting is that while this style of documentary filmmaking has become less popular with filmmakers, it has simultaneously been embraced by comedians like Hannah Gadsby and, more controversially, Dave Chappelle. In Gadsby’s 2018 Netflix special, Nanette, the comedian took the opportunity to make her stand-up routine more than just a recital of jokes. Part-way through her set, while talking about how she always used to make fun of herself on stage for being a lesbian, she announces to the audience that she will never again diminish her sexual orientation and gender identity in exchange for a few laughs. It’s a powerful and striking moment.

17 minutes into her 70-minute set she says without blinking, “I have been questioning this whole comedy thing; I don’t feel very comfortable in it anymore. I built a career out of self-deprecating humour, and I don’t want to do that anymore. Do you understand what self-deprecation means when it comes from someone who already exists in the margins? It’s not humility—it’s humiliation…and I simply will not do that anymore. Not to myself, nor anybody who identifies with me,” to which she receives raucous applause from the several thousand people in the crowded auditorium.

In the same way that Al Gore relied on jokes in his lecture to carry his message, Gadsby uses this moment of gravitas in her comedy sketch as a way to punctuate her message. Several times throughout Nanette, Gadsby inflects her comedy routine with moments of seriousness dealing with homophobia, sexism, sexual abuse, and hatred. She even tells incredibly personal stories of experiences she had with sexual abuse as a child and assault and rape as an adult.

In this way she offers a vivid illustration of why we continually need to move towards humanity and acceptance. Although she doesn’t rely on any visuals behind her on stage, her exhilarating performance carries the same level of passion and force as the arguments presented by any speaker in a lecture-style documentary.

Controversial comedian Dave Chappelle also uses historical and personal storytelling in his own comedy routines, but in a much more complicated and divisive way than Gadsby. In an echo to Nanette and in response to criticism from his previous comedy routines, Chappelle’s most recent Netflix special, The Closer (2021), directly takes on LGBTQ and feminist issues. He relies on his own personal experiences mixed with America’s anti-Black racism, sprinkling in references to Sojourner Truth and Juneteenth, as a shield against criticism for his transphobic and homophobic views.

Chappelle’s comedy special has a goal of not only making people laugh (and feel uncomfortable) but of undermining the rights of LGBTQ people and women. His routine is as equally filled with hate as Gadsby’s is filled with vulnerability, and both have the result of galvanizing their audiences.

It is crucial to point out that Gadsby’s work is lauded by the media and Chappelle’s work is strongly criticized.

We find ourselves at a moment when conservatives and authoritarian governments have found a greater voice in society. The type of grandstanding we see from people like Dave Chappelle may very well increase.

Comedy routines, lecture-style documentaries, sermons, and activist speeches are all popular for a reason: As humans, we strongly respond to storytelling and debate. Lectures aren’t going anywhere, nor are the films that will be made from these talks. The Internet will ensure that these talks will find an audience online no matter the size.

As ubiquitous as the lecture-style documentary and its televised offshoots are, it’s surprising that a search for lecture-style documentaries online doesn’t turn up any results. It’s not a genre of documentary that has been greatly studied, nor is it even generally taught in universities. (Is lecturing about a lecture-style documentary just too meta?) It may not be sexy, but there is a purity to the form that ensures this style of documentary will continue far into the future in a variety of new and different formats.