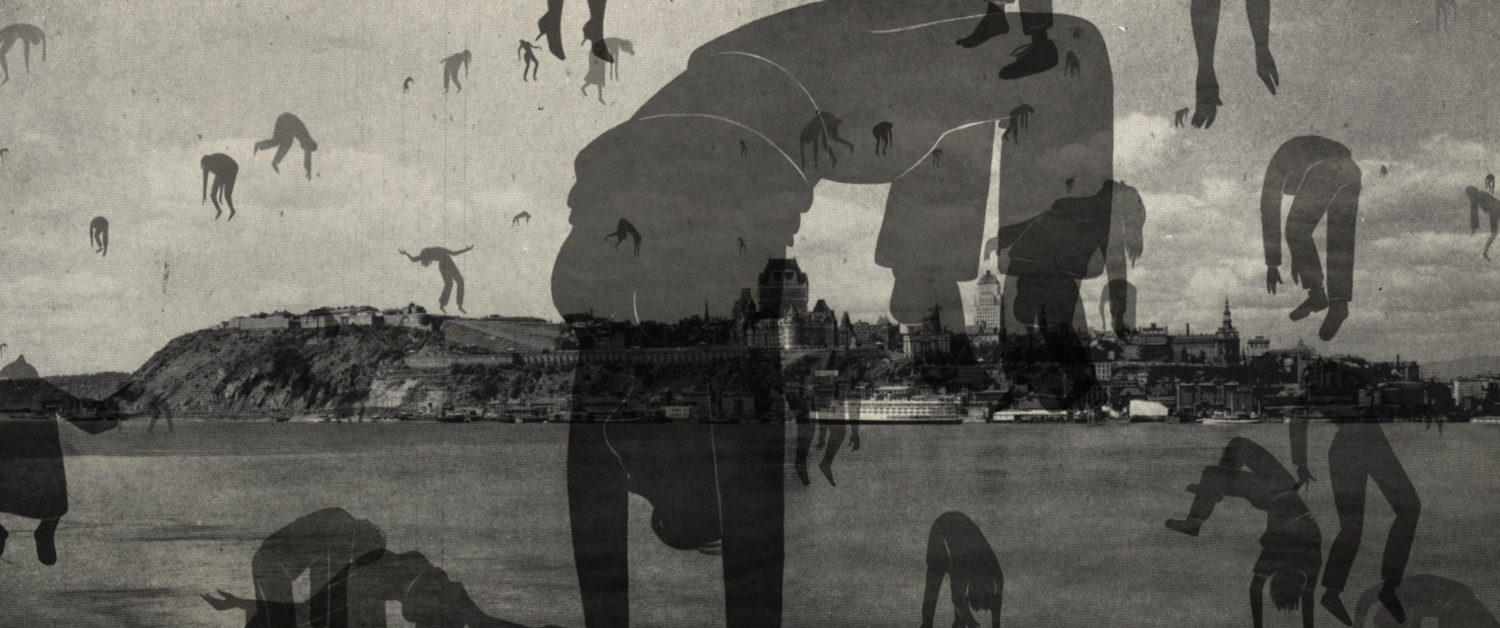

Much of 2020 was shaped by moments captured via cellphone in which police officers were seen leaning on the neck of George Floyd as he gasped for air. This brutal act of violence inspired conversations ranging from surveillance to police brutality and the systemic forces that balance liberty and security. In profound ways that defy expectation, Theo Anthony’s exceptional All Light, Everywhere dives into these myriad aspects of our society, deftly navigating between highly intellectual and rarified elements with the pragmatic reality of life on the streets.

From a tour of the Taser corporation to a fascinating town hall meeting about aerial surveillance, Anthony’s film feels at once like an icy bit of journalism and a mind-expanding philosophical treatise. Like 2017’s brash and brilliant Rat Film, Anthony once again tackles extremely complex ideas and reflections while presenting these elements in a means that completely engrosses a viewer. Through an almost synthesized voiceover, we experience the wanderings through the modern world, ever conscious of what takes place outside the frame of the image as well as parsing the motivations of those living behind the lens. It’s quite the magic act, and while its surreal and occasionally somber take may be off-putting for some, those willing to engage with its unique brand of cinematic richness and philosophical depth will be in for an unforgettable experience.

POV spoke to the Anthony prior to the virtual premiere of All Light, Everywhere at Sundance 2021.

POV: Jason Gorber

TA: Theo Anthony

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

POV: I think your films are expanding a kind of Baltimore gothic. If you look at what Barry Levinson has done, or David Simon, or John Water, you’re all following Edgar Allan Poe. What is it about Baltimore where you can get these stories that have such specific local aspects but also global interest?

TA: Baltimore is just not New York and not L.A.. It doesn’t have this massive infrastructure of industry that’s centered around creative arts. For a lot of us, filmmaking didn’t start out as our day jobs, so there’s just a spirit of collaboration. It’s not limited to film; it’s the same with the music scene, the arts scene, the fashion, as everything is just so intermingled here. Baltimore has the infrastructure of a major city, but is way smaller. The population has shrunk by half since WWII. There’s a lot happening here politically, obviously, and I think that places a responsibility for artists to engage with that. You listed some amazing names, but also I look at people now, who are my friends. Albert Birney also has a film at Sundance, Strawberry Mansion. Then there’s Marnie Ellen Hertzler, there’s Zia Anger (my girlfriend and also my favourite filmmaker), and Cory Hughes. All of these people are really engaging with this city in fascinating ways and interrogating their own role in it. There’s something unique to being from Baltimore and it’s such a beautiful place to live and make art.

POV: You also seem unafraid to let your films deal with the sociology and politics of the situation, but also the horror and the surrealism of the situation. How do you navigate these tonal shifts while not becoming didactic? This film and Rat Film gently take us along this river, even if the river becomes Styx at some point in time.

TA: I’m glad it doesn’t feel didactic and overly prescriptive. I always have these larger questions in mind about power and politics, and I am always looking for those relationships between the world and representations of the world. That exists in that act of translation, and you saw it with Rat Film, you saw it with Subject Review and much more explicitly with All Light, Everywhere. I feel like I’m a magnet constantly passing over and occasionally picking up images or stories that stick to me. If you allow yourself the time and the silence, some quieter and less obvious connections begin to unfold.

A lot of the conclusions that I draw are not particularly revelatory. If you live in Baltimore, you know it’s segregated, and everyone knows that there’s a problem in policing with systemic racism. But I try to take these seemingly obvious things and stick with them long enough and just pull the thread gently to see the really non-obvious ways that it manifests itself. That’s part of not being didactic about it. I want people to feel like they’re taking part in that as well, so they can connect with these stories. The entry points are so wide and so familiar that I hope they can provide a way for people to see it [systemic racism] and how it manifests in their lives in new ways.

POV: It wasn’t until the protests last summer that I actually learned that Taser makes both the stun gun and the camera. Your film obviously conflates those in really interesting ways without being judgmental, just simply pointing out the fact that here’s an aspect of police-military complex. How has your own journey about this shifted, your back and forth about some of these technologies where we live with a modern panopticon?

TA: As per my previous films, I was always interested in the power dynamics of the frame and of the act of filming. A lot of the seeds for this project came from after the killing of Freddie Grey in Baltimore. That was when the justice department came in with their consent decree requiring all officers in the Baltimore Police Department to wear body cameras by the year 2018. I was reading about it and I saw this really compelling connection. That reform was really popular, but the more I looked into it, I saw it had some problematic undercurrents, especially when you realize they’re a weapons company that has rebranded to policing body cameras. That all came out of the Baltimore uprisings, where besides all of the great things in terms of organizing and elevating the conversation in the city, there was also the deep tragedy – not just of the killing of an innocent man, but also that loss of hope that we can change things.

Once things quiet down, you see how the stone cold bureaucracy seeps in, solidifies everything, and makes it impossible to change. This project started four and a half years ago and there’s always a worry that we’d get eclipsed by the news cycle, wondering if by the time it’s done are people even going to care about it. We were about to go to war with another country over a tweet, and it just seemed we’d tripped into the singularity. With the film, we were going more abstract and wider, and then the pandemic and the murder of George Floyd happened. That moment focused us and brought us back down to ground. We all saw a video of a man murdered by a police officer. There’s the truth that he was murdered, but still people have different interpretations. How much clearer do you need it? In that same breath, people are asking for body cameras to address that, with this undying optimism that if we can see it, we can understand it and we can change it. That was what we wanted to interrogate. That closed loop of seeing no change is where power really consolidates itself. So, in a very practical, material way, we saw a way for us to help educate people about how body cameras work. That wasn’t our central mission, but it was very real and practical.

POV: How has that change of view shaped your own reaction to what took place?

TA: Outside the film, I’ve been getting involved in policy reform around body cameras in my hometown of Hudson, NY. That’s been a really incredible process. There’s this little art film that I made, but when we get down to policy, this is something we can change right now. No one knows how these things work, and a lot of bullshit is flying under the radar. For example, officers are still allowed to review footage before making a sworn statement. That’s a pressure point for us to come in and change to make sure that if cameras are already here, they can’t be used for these worst case scenarios. The protests reinvigorated us, and brought us back down to earth at a moment when the film was getting abstract and conceptual. It brought us back into our bodies to connect to the here and now, to the present, to the material.

POV: There’s a danger with films like this to lean too far into advocacy because then they becomes not only political, but oftentimes propagandistic. On the other hand, it could be too easy to lean into the art, which makes it too distant from reality. It could also lean too heavily on the journalistic and become dry and prosaic.

TA: I’ve been doing a lot of thinking about what a film can and can’t do. At this stage in the culture wars, there’s this expectation that a film itself has to be a political act. The liberating thing that I realized this summer is that I can be doing this and amassing this knowledge, but there are other outlets, either through organizing, through my community, or through policy reform, that I can direct that energy to. That takes the pressure off the film. Film can provide a space where you hypothesize or propose things, yet the need reduce that to a message or a takeaway limits what it can do. Obviously I am politically motivated. It’s a long, uphill battle for these changes, and I’m learning so much by writing policies and familiarizing myself with the legal language of how this all works. That’s completely the other side of the process from filmmaking. Earlier cuts of the film didn’t have any of the legal language in there. For the past six months, I’ve been on a police reform committee in Hudson that was initiated by Mayor Johnson, and we’ve been tasked with taking a hard look at the policing and having conversations with the community. It’s been very interesting, and very frustrating, to try to actually get it done. And that’s absolutely affected the film.

POV: The ability of the film to stand alone is that it should provide space for those that may vehemently disagree with all of your reform proposals or your politics. To its credit, there is space for everyone in this film, as it treats the audience with intelligence.

TA: That’s absolutely our strategy. You were asking about the edits – it was always a matter of pruning back and pruning back with just enough there so that we had a foundation for the audience to come in and stand upon. There’s are certain works that, as an audience member, make you feel that you have to be smarter to understand, and that you have to jog through it. I want people to be in on it, feel smart going through this, feel like they’re going through the connections and making it for themselves. I think that even goes for some of the disconnected or sparse nature where I back off from things. I want to lay the groundwork. I have faith in my audience to step up to the plate and complete the picture for themselves. People are talking to each other and helping to fill out the spaces in the film.

POV: Are there specific instances you can think of when a colleagues’ work went too far towards the polemical? It could even a film you love, like The Thin Blue Line, something exceptional but you realized that kind of certitude was not right for this story?

TA: In documentary conversations, the most obvious and the most central thing for the scene is the least talked about, namely the camera. It’s a huge object, and it places the person behind it in a certain position, while placing the person in front of it in a different position. It changes the person being filmed and it changes the person who is doing the filming and I’ve always been interested in that process. It doesn’t mean that it has to be like it’s an endless self-reflexive journey, but that we need to incorporate that into any conversation about truth. I bristle when there’s any discussion of a journalism piece or anything that just throws the word objectivity around. I do think that true stories exist. I do think that there is some truth that exists, but you really have to incorporate not only yourself and your journey of finding it but also the people who are helping you find it as well.

POV: You have a Rodney Ascher film to watch.

TA: Oh yeah, A Glitch in the Matrix! It’s on my list.

POV: Are you a filmmaker who watches documentaries in order to shape your documentary?

TA: I’m going through a movie stage right now, but I’m watching a lot of blockbusters and stuff, honestly. I go through waves. I’m not watching a whole lot of documentaries to be honest. My girlfriend and I just binged the Harry Potter series.

POV: The Cuarón one’s great.

TA: It’s amazing!

POV: He makes Hogwarts a character. That’s what’s so great about the third one.

TA: I’ve been so deep in this theoretical world for so long. Everything I read is surveillance or history. I’ve been so deep in the editing of my film that I just to return to just the pleasure of looking and being enraptured, so it’s not that deep! I also just really enjoy the act of movie making. I included a bibliography at the end of my film for a reason. I think there’s such a huge body of work out there and I’m not coming out of nowhere. I didn’t initially discover any of the things in my film, and I’m inspired by what I read. I encourage people to take screenshots of the bibliography and use it as a jumping off point into other people like Simone Brown or Donna Haraway. These are the people whose DNA is in the film. When I read works like that it gets my gears turning the most about the types of films that I want to make.

POV: What’s next for you? I know that’s a terrible question when we’re at a festival, but is this now firmly your schtick? Are we too quick to put you in this box of the cerebral filmmaker who’s deconstructing the way we view all reality?

TA: What a box! [Laughs.] I really need to take a break. This has been four and a half years, and it really swallowed up my life. I became a shell of a person at the end where everything I did or thought or read was funnelled into this project. I know everyone has their quarantine hobbies and stuff like that, but I actually like having that break. It’s so important to me to realize that I need to be doing other things with my life that I can funnel this passion into. I’ve been very excited about woodworking and playing Go and reading. I’m really looking forward to having more time for those expressions of myself. Through that, I will figure out what I want to do next.

POV: You’ve literally spent four and a half years on a film that is all about looking as closely as possible at something, and about the internal focus. Can you close this chapter of your life as a filmmaker, or would making a film about something comparatively more frivolous seem like a failure?

TA: I did a lot of processing with this one that I definitely don’t have to go through again and again. Yet that’s the foundation I’m always building on. I think I’m always going to want to maniacally explore and build and just figure out uncanny connections between ideas. That’s just how I think, and I don’t really know any other way to do it, regardless of what box you may want to put me in. I can’t follow or tell a linear story. Whether it’s a woodworking project, or a film, it’s about the understanding of material and process combine with a deep, maniacal obsession. That’s just how I’ve learned to move through the world. Whatever project it is next, I’m sure there’ll be a lot of that in it.

All Light, Everywhere premiered at the 2021 Sundance Film Festival and has its Canadian premiere at Hot Docs.