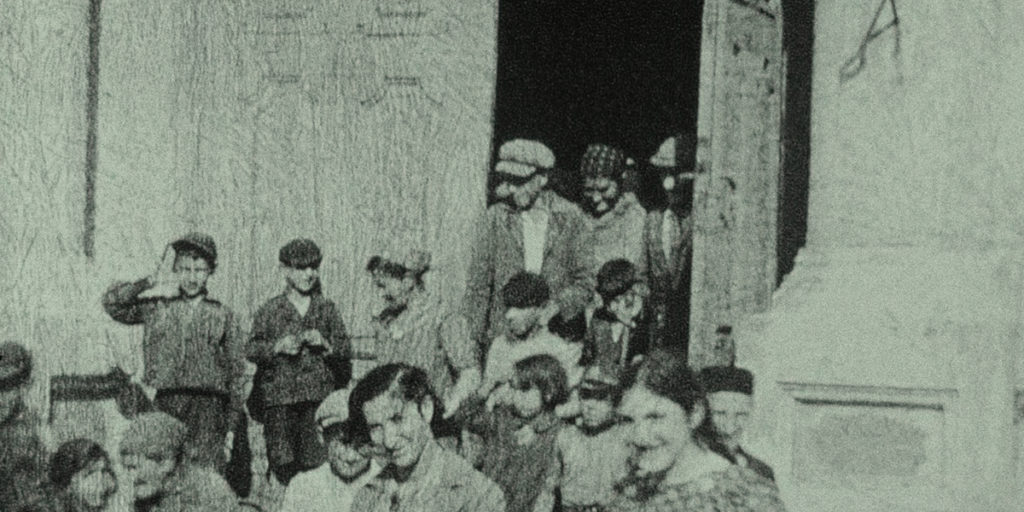

In 1938, David Kurtz returned to Poland, visiting the land of his birth years after achieving financial success in New York City. He brought along a portable camera and some film, a relative rarity back then for a tourist to be schlepping, and captured images of the architecture and people of small Jewish communities such as Nasielsk. The footage shows throngs of locals enamoured with this foreigner waving his contraption about, their excitement of being caught on film palpable as they crowd to be counted, waving and clamouring for attention. Soon almost all of them would be dead, victims of the Holocaust, a wholesale human slaughter that seems a world away from these smiling, laughing moments caught just before the storm would set in.

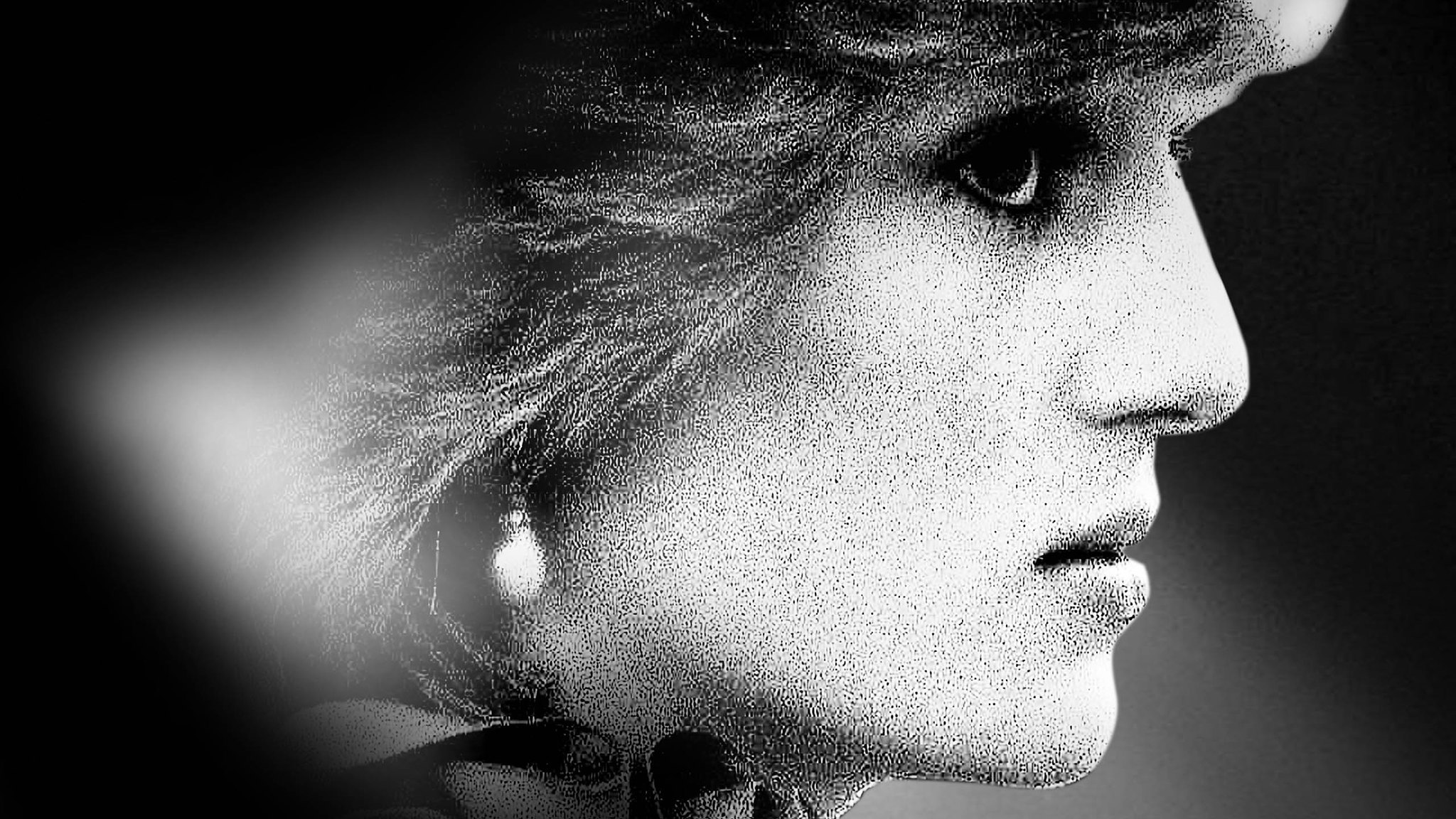

Bianca Stigter’s Three Minutes: A Lengthening begins with Kurtz’s travelogue shown in full, recovered after years of being held in storage. The original footage is a bit pedestrian, with a constellation of round faces with dark eyes, wearing simple outfits, all blurring together. The first time through it’s almost boring, as banal as would expected when watching a stranger’s vacation footage.

The buildings in the background evoke generic European lower-class residences that could be from almost anywhere in the region, providing a challenge for contemporary historians when they narrowed down the actual location. It’s almost magical that the memories of the Jews who lived in Nasielsk have been preserved.

Stigter’s film-about-a-film evokes the difference between watching and seeing. With the former one merely apprehends what’s provided to you on screen while in the latter, there is an active engagement. Stigter entices the audience to seek the story behind the pictures, investigating the lives behind the faces, and delving with forensic acuity into the street signs and other details that are inevitably missed the first time one experiences the footage.

French philosopher Michel Foucault begins his 1966 book The Order of Things with a captivating discussion of Diego Velázquez’s 1656 painting Las Meninas. It’s a subtle, elegant analysis of a painting that had long been celebrated. Foucault goes beyond the subjectivity of who is captured on the canvas, the “classical” form of representation, and delves more into how those individuals are captured, with the power of their reciprocal gazes creating a “complex network of uncertainties.”

A key feature of Las Meninas is the mirror seen on the back wall, where Velázquez has painted a reflection of King Philip IV and Queen Mariana. The artist himself peeks out from behind a giant canvas, making the subject of the reflection—us, the audience—equally the focus for the painting-within-the-painting. We become both subject and object, and as viewers we are standing in for the royals and also are the royals, to some extent—witness to the capture of their image, hundreds of years after their deaths. It is art about art and forces us to reflect upon the very nature of what we are perceiving.

Foucault’s discussion of the painting is a metaphor for his larger thesis, illustrating a more active way of seeing, where the mechanistic, aesthetic, and historic aspects of what’s captured in a frame shape in myriad, interconnected ways our own entanglement with any artwork. This shapes not only what we know about what’s captured, but how we know. Foucault is giving us the tools to interrogate the very questions we ask about what it is that we are perceiving, and how our tools of perception shape what we know to be true.

There’s a dense analysis throughout many of Foucault’s writings about how being viewed, or simply the possibility of being watched, shapes our behaviour, and that history itself, and in turn truth itself, is shaped fundamentally by what’s being viewed and how it’s seen. To see rather than just watch shifts what and how we remember. It is not simply the rewriting of history, for to look at not only what memories are captured but how those memories are captured is itself an active act of truthmaking.

Stigter’s film occupies a similar complex space, where we’re not only watching Kurtz’s footage, but seeing it in increasingly complex ways. When we view what is captured, we are living in two distinct yet inexorably interconnected spaces.

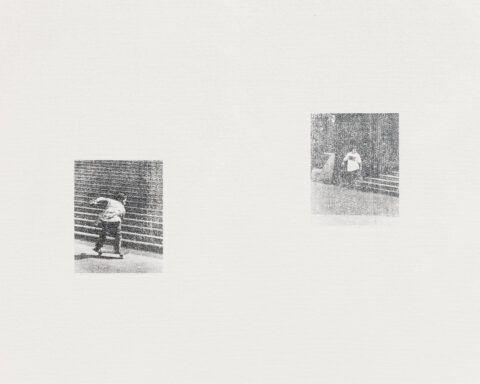

The first is the capture of the time and place of 1938 Poland as it was—and was never again to be. The restricted gaze of the lens sweeps the landscape, capturing not only those cramming the foreground of the shot, but also those looming in doorways or watching with bemusement as the crowd gathers in front. Stigter stitches multiple frames together to create a still panorama, a painting-like portrait of that moment where the shifting, smiling faces blur into one another.

The second space is the viewer’s engagement with the inexorable sense of doom evoked by Kurtz’s film. It’s akin to watching the last glimpses of extinct creatures just prior to their extermination. We see the smiles and can almost hear the laughter and voices, while knowing that almost all would soon be snuffed. Like with Las Meninas, the imagery can be thought of as an eerie time machine, a portal of sorts to engage with the gaze of the dead. Whether the court of a Spanish king or a community soon to be slaughtered, we as viewers are shaped by their stories, and how closely we engage with their stories shapes their past in a similarly dynamic manner.

I have a very old photograph of family members on my wall, with round faces and dark eyes not dissimilar to those that Kurtz’s footage would accidentally immortalize. It was captured in Yekaterinoslav, then part of the Russian Empire and now Dnipro in Ukraine, sometime before 1910, and has the patina of another age. It shows a stoic-looking family dressed in black, arrayed in a line. Seated are Avram Lagunow, with short cropped hair and a long beard, and his stern looking wife Esther. Standing are their children, all staring at the camera, and, as in Kurtz’s films and Velázquez’s painting, gazing back at us through time.

On the table within the portrait is a small rectangular photograph, extremely challenging to see. On that image of an image is Henry Lagunow, whose Hebrew name Yehekzel I share. In 1905, he fled the army and got on a boat to a strange and foreign land. His image was included in the family gathering, even though he was thousands of kilometres away in a strange and hostile land north of Montreal.

This is not only the representation of a family, but also of extermination. It is only Henry’s lineage that has survived. From pogroms to two world wars and the Shoah, the lives and direct lineages of everyone else in that photograph were ended, save for the one who wasn’t there the moment it was captured. Like with Kurtz’s footage, it is only the person represented in the representation, the picture in the picture, my father’s grandfather, that still has people around to tell his story.

The power of Stigter’s film lies in how it lengthens these three minutes of footage into an exploration not just of a people long gone, but the lives that the representation itself represents, well outside the footage that Kurtz shot. It’s history reclaimed, with witnesses remembering the trivialities that inject so much life into the two-dimensional images. The documentary encourages us to look close in order to see, to engage with the interconnection or “complex network of uncertainties,” where we’re positing the thoughts and feelings of those that can no longer speak for themselves. As viewers we are witnessing what’s captured, while privileged by our secure position behind the camera, as if it were our own hands swinging the camera, the lens our own eyes there to bear witness to these individuals, secure through the divide between us and the subjects both physically and temporally.

There is a Jewish saying of condolence, “may their memory be a blessing.” One thing that the Holocaust did systematically and purposefully was to erase those who would be around to remember, a wholesale attempt to not simply murder people but to eradicate them, their religion and their culture, for all of time. Just as the Romans would salt the earth when abandoning an area to prevent anything else growing in the future, so too did the Nazi regime attempt, through liquidation, a complete cessation of all lines of remembrance. It’s another level of destruction, and all the more insidious, a particularly cruel fate meted out to individuals who tightly hold on to memories of the past and who for millennia have been referred to as the people of the book.

Implausibly, perhaps, some stories manage to survive, despite the massive efforts of those intent on slaughter. A film canister found decades later contained more than mere trivial vacation ephemera, and witnesses of the community were still alive to tell tales and bring names to faces of those that Kurtz caught on celluloid.

Stigter’s Three Minutes: A Lengthening reminds us not only how fragile our lives are, but how fragile our history is. Save for a few happy accidents—film footage kept intact, a photograph of a photograph maintained in good condition—those now remembered would be erased forever. Stigter’s film stands in for all those who were never photographed, whose lives truly were erased during this time of madness and destruction. But it’s also a film for us now, to reflect on the fragility of our memories and histories even while there are those around to provide supporting testimony.

There has never been a time in human history when it’s been easier to capture images from innumerable perspectives, yet seemingly there’s never been a greater gulf of interpretation for these events, with political and social divides becoming increasingly poisonous around the world. Stigter’s film asks us to slow down and view with greater acuity, demanding that we take the time and recognize both the power and limitation of our modes of gazing.

As Foucault’s analytical methodology encourages, Three Minutes: A Lengthening reveals a complex web of relations between ourselves, the past, and artwork, one where we witness behaviours changed by having been seen by a camera, and our observation decades later changing what is represented in the frames of the film by bringing into play our own knowledge of what would soon occur.

We see what Kurtz saw through that lens in entirely different ways, but we must also try to see how he saw them. We must try to understand that those looking into the camera saw a moment of joy, even while bowed by the recognition that they had no conception of what was to befall the vast majority of them. We must see, rather than simply watch. In doing so, we don’t simply understand or comprehend; we actively remember. In some small way, through that process of remembering, we provide a blessing to those that have long been lost.

Three Minutes – A Lengthening screened at the 2021 Toronto International Film Festival and screens at the 2022 Sundance Film Festival.

Read more about the film in our interview with Bianca Stigter.