“The hard part was convincing people that you’re going to do good—that you’re here to tell their story truthfully, honestly, and fairly,” says director/producer Matt Gallagher on his documentary Shamed. “People lost relatives who died by suicide or by a drug overdose.”

The veteran filmmaker says that Shamed presents the biggest challenge of his career and it’s arguably his toughest film to watch. Shamed, which premieres at Hot Docs, recounts the story of Jason Nassr, a vigilante YouTuber based in Windsor, Ontario. Nassr shares how he entrapped men whom he suspected of being pedophiles by posing as minors online, building relationships, proposing public meetings, and then confronting them on camera to “out” them via his channel Creeper Hunter TV.

Shamed tells how Nassr’s plan backfired. Instead of landing these guys in the slammer, he himself was convicted on charges including production and distribution of child pornography, extortion, and harassment by telecommunications. These charges do not cover the deaths left in his wake. Shamed considers the moral crimes that Canadian laws have yet to catch up with in the online age.

Processing the events on screen, meanwhile, proves a rollercoaster of discomfort. Audiences must ask themselves to weigh Nassr’s mission to protect children by hunting presumed sex offenders with his twisted methodology. Alternatively, one can consider Nassr the story’s one true predator. Shamed offers a prescient parable of what it means to be tried and crucified in the court of public opinion when any person with a platform wields the power of judge, jury, and executioner with one click.

Gallagher, joined with producer Cornelia Principe via Zoom, tells POV that they connected with Nassr while he awaited sentencing. “Cornelia and I did a documentary years ago called How to Prepare for Prison (2016), and found there’s a window for many crimes between the time that you’re convicted to the time that you start to serve your sentence,” explains Gallagher. Such a window proves advantageous to learn more about a person’s story during a period of reflection. “I basically wrote an email, and to my surprise, he responded. And the next thing, I was down in Windsor and we met for a coffee.” (Nassr eventually got a mere 18 months’ house arrest, which he’s appealing.)

“I was always curious about this aspect of vigilantism and the kinds of videos that he was doing,” says Gallagher. Nassr’s work offers a copycat of sorts of Chris Hansen’s hit series To Catch a Predator, which, incidentally, has its own documentary this year with Predators. Yet Nassr’s fascinating psychology easily sets the films apart.

“Interestingly enough, Jason was the easiest person to get in the chair,” adds Principe. “And then he cut us off. He realized that we weren’t necessarily on his side or that we weren’t there to bow down to him.”

Besides observing the judicial/sentencing process in How to Prepare for Prison, Gallagher and Principe previously took a sensitive approach to a similarly difficult subject in Prey, their 2019 Hot Docs Audience Award winner about a survivor of clergy abuse suing the Basilian Fathers of Toronto. (Principe also produced the Oscar-nominated To Kill a Tiger, about a young survivor’s defiance of the patriarchal status quo in India.) Gallagher notes that Prey proved beneficial to their approach, and helped to convince Nassr to tell his story, having seen the award-winning doc and been impressed by it.

“Because we did a documentary on clergy abuse, maybe he sees himself in a similar light—attacking the bad person and stopping this thing,” says Gallagher.

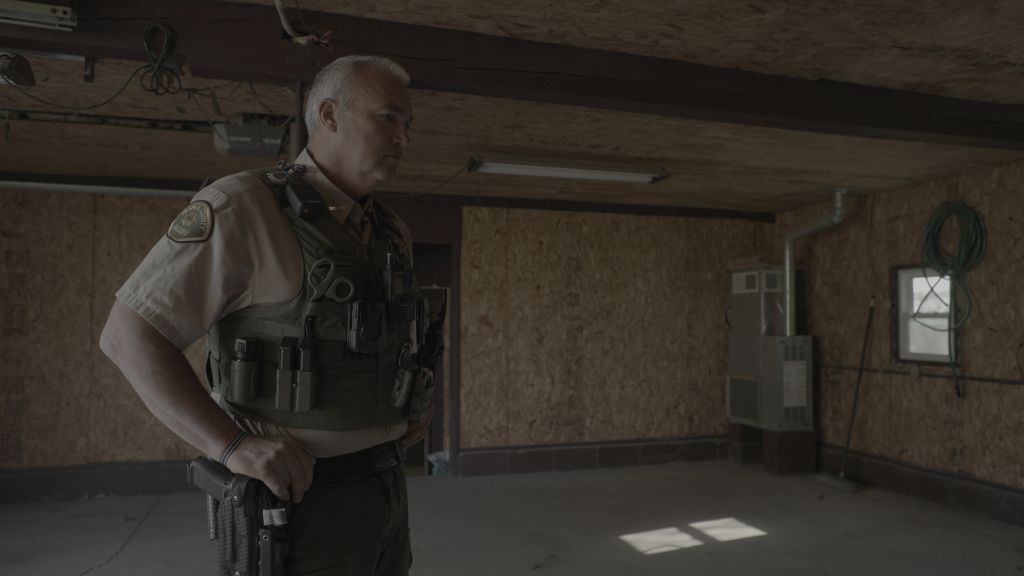

As Nassr outlines his mission across four interviews, and takes Gallagher to hunting grounds where he shot his videos, it’s evident that he truly believes he does justifiable work. However, as interviewees like journalist Jane Sims note in the documentary, there’s no proof that any men in Creeper Hunter’s catalogue ever acted upon their alleged pedophilic impulses—or even had them, given that Nassr contacted them through adult dating websites.

Shamed puts audiences in a position of extreme discomfort, but with a purpose. It presents men accused of the most heinous of crimes and asks audiences to sympathise with people who had no chance to clear their names in the court of public opinion.

“Once Jason pointed that finger saying, ‘You’re a predator, you’re a pedophile,’ these men did not recover. Their families walked around with that shame too,” says Principe. “Our documentary might be the start of people being able to talk about this more: of shaming people, and this idea that just because something’s on the internet that it’s somehow real.”

“The tone in this film is a really difficult needle to thread,” adds Gallagher. “Our editor, Nick Hector, has been working on this for two years, and we’ve come up with something like 57 versions of this film. The most difficult part of the film is: how do we feel about this?” It’s an odyssey guided by dramatic turns through unease, anger, and compassion.

Moreover, Shamed avoids replicating Creeper Hunter’s salaciousness: the filmmakers’ portrait of Nassr isn’t a one-note snuff piece. Shamed reflects the journalistic rigour that distinguishes documentary from Nassr’s “gotcha” pseudo-journalism. It considers all the factors entailed in a story to inspire audiences to think more critically about the world around them.

There’s a fascinating dynamic to Shamed, too, as Nassr’s interviews show nothing of the combativeness he displays with police and the belligerence with which he answers prosecutors. His years speaking with an unfiltered platform reflect how online predators, mischievous influencers, and malicious tweeters often throw words into the void without consequences.

“There were times when I asked him a question and I believed he was truthful and honest and forthcoming. There were times when I didn’t believe him,” says Gallagher. “There were times where I thought he was playing with me, but the most honest I’ve ever seen him is in his own videos that he’s already created, where he talks to his fans. That is Jason unvarnished.”

The filmmakers note that Nassr’s archive was at their disposal before the courts ordered its deactivation. The uncomfortable task of sifting through the videos, they note, inspired them to ask what happened to the men after publication. Shamed explores the stories of five men who died either by suicide or by drug overdoses after appearing in Creeper Hunter videos.

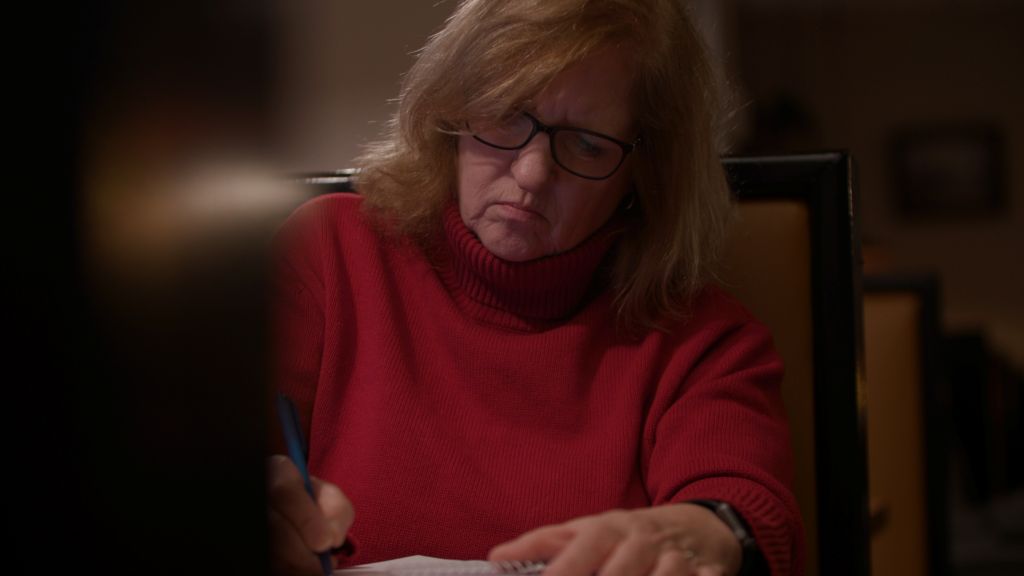

The case of John Doe #80 sees a woman recall how her partner was ostracized at work after Nassr waylaid him. She tearfully tells how she stood by him while he lost his job and unravelled. Eventually, the film shows that #80 begged Nassr to remove the video, giving him a firm deadline or else he’d kill himself. She shares that her partner died in an overdose while the video accumulated likes and shares.

Then there’s the distressing case of John Doe #30. When Nassr confronts him, the man shares that he is a survivor of childhood assault. He asks Nassr for help. In a move that may temporarily surprise viewers, Nassr accompanies #30 to a sexual assault crisis centre. However, it quickly becomes apparent that Nassr’s interest resides in getting juicy material for his channel. The social worker, slightly bewildered by Nassr’s presence, asks about his role as a journalist while John Doe shrinks in the corner.

“Are we going to talk about me now?” John Doe asks with audible desperation. He, too, dies shortly after Nassr publishes the video.

That scene provides a jarring moment. Even audiences who consider Nassr’s intentions virtuous must be somewhat shaken. He shows no interest in understanding the root causes for the behaviour he seeks to expose.

“The story’s not so much about Jason. It’s about the collateral damage that happens when a man like Jason is allowed to operate,” says Gallagher.

Evidence of collateral damage appears through interviews with friends and family—testimonies wrought with grief, anger, and pain. Among the key interviewees is Brett (a pseudonym), the brother of a late John Doe wrongly accused by Nassr. Brett shares his discomfort in Shamed’s uncomfortable opening scene. He makes it clear that he doesn’t want to be in the movie, but he’s doing it for his brother, whose mental health challenges provided Nassr with an easy target.

“Strangely, with Prey, people were more willing to come forward and talk about it rather than this one,” observes Principe. “In this particular film, we were only talking to families, not the actual catches—although we did talk to a few of the catches, but they didn’t want to go on camera—but they’re traumatized and, in some ways, more traumatized, because it happened much more recently.”

However, thanks to Brett’s desire to clear his brother’s name, his participation accounts for one of the film’s breakthroughs. The filmmakers credit Brett for providing his own research that helped them connect with many lives affected by Jason’s videos.

When Gallagher asks Nassr how he feels about one of the suicides spawned by his videos, though, the Creeper Hunter says he knows only of one. His response to Gallagher is chillingly telling.

“Do I feel bad that he’s dead?” Nassr reflects. “Sure, I guess. It sucks to be dead.”

Those words provide a startling moment halfway through Shamed. Prior to the interview, there’s an arresting shot of Nassr, viewed from behind, watching his video of John Doe #30 as the man asks for help. Nassr shows no remorse for milking #30’s illness, pain, and desire to recover. The shot anticipates a moral reckoning that never comes.

“When I interviewed him the first time, I was genuinely curious,” says Gallagher. “I thought, ‘This is going to be one of those films where the protagonist has some redemptive moment and they’re going to confess and heal.’ I thought that, maybe after being convicted, Jason would say, ‘I made a mistake and I shouldn’t have done this. I feel bad.’ That didn’t happen at all. In fact, he doubled down on all of it.”

To Nassr’s credit, as Principe points out, he answers every question they ask him, even ones he clearly dislikes. “He is very belligerent with the cops, but he answered every question. He may not have been totally forthcoming with everything, but he certainly answered every question.”

“Do I feel bad that he’s dead? Sure, I guess. It sucks to be dead.”

Jason Nassr in Shamed

The dynamics between interviewer and interviewee in Shamed prove fascinating. Nassr’s videos display a lack of empathy, whereas the documentary holds onto that courtesy. But after Nassr’s “it sucks to be dead” nugget, Gallagher says he heard enough.

“That was the last thing I asked him. At that point, I was trying one last time to reach out and see if there’s anything there that could be redemptive or regretful,” says Gallagher. “When he said that, my next comment was to the crew. I said, ‘Okay, guys, that’s it. Let’s pack it up. We got it.’ That was the last time I spoke to him on camera.”

“It really shocked us,” agrees Principe. “Part of you that doesn’t even know quite how to react to someone when he says, ‘It sucks to be dead.’”

The absence of remorse ultimately makes Shamed more satisfying. When one door closes, more open.

“This is a story about how individuals can take advantage of the internet, take advantage of people who want to somehow feel like they’re doing something just,” says Principe. “I don’t like this idea of shaming people. It’s distasteful and it’s wrong. There are other elements that I think are valid. I think empathy is always important.”

Shamed observes how Creeper Hunter’s phenomenon is not an act of protecting the innocent but rather an exercise in the depths of human cruelty. The ease of Nassr’s participation over that of innocent parties speaks to the stigma entailed in defending the seemingly indefensible. “We made Prey in 2019,” notes Gallagher. “We’re at a point where survivors of sexual abuse, clergy abuse, or any sort of abuse were celebrated after #MeToo. People wanted human stories about it. They’re given love and support, and we believe them.”

For all the justified outpouring of support to survivors’ stories amid #MeToo, Nassr’s prey doesn’t receive the same consideration. Brett and others testify to what it means to see such malice unfold in real time.

Shamed sees the chilling bandwagon effect that leads to tragedy. One story recalls a mob that plastered a community with signs about a pedophile in their midst as crowds formed outside the John Doe’s house. One neighbour tells Gallagher it was like watching a lynch mob. Another admits that he joined the crowd, but can’t really articulate why.

The film intercuts its analysis of the lateral violence of Nassr’s work with his testimonials from Creeper Hunter in which he incited the mob. The message of one sicko predator inspires a movement of people governed by impulse rather than a desire to understand. The film illustrates the recklessness that fuels media consumption in the age of viral videos and trending topics.

The conversation with the filmmakers takes a different turn when POV asks Principe if it’s a phenomenon to which she relates, having weathered an online storm after protesters branded her documentary Russians at War “propaganda” before it even premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival last fall. (The screening was temporarily cancelled amid credible threats to the filmmakers.) While the circumstances are obviously different, one sees parallels to the challenging if nuanced portrait of the Russian army in disarray: the film got stuck with a label that doesn’t fit.

“Having a film called a propaganda is almost like being someone being called a pedophile,” agrees Principe. “It’s really hard to walk back from that unless you actually know them. When people see the film [Russians at War], they say, ‘It’s not propaganda,’ but propaganda as a label is really hard to undo. So to some extent, we’re embracing the controversy. It’s the fog of war, really.”

A similar ethical haziness makes Shamed noteworthy as it tasks audiences with reaching moral clarity. The film, moreover, premieres with the support of Ontario public broadcaster TVO, whose board of directors quickly capitulated to the online mob and pulled funding for Russians at War, surprising even the programming department. Principe diplomatically says that she and TVO “reached a mutually acceptable agreement” and that the issue is behind them now—proof that tough conversations have their benefits. Similarly, it demonstrates the necessity of supporting challenging works at a time when documentary programming favours milquetoast music docs and flattering biographies—surely a factor in Nassr’s assumption that the film would uncritically platform him.

The result of putting in the hard work appears in Shamed’s devastating finale. As frustrated friends and family leave Nassr’s sentencing, one woman turns to Gallagher. She says that she hopes justice is served by this documentary since the courts failed them. It’s a big responsibility, but one that the filmmakers accept.

“I want people to understand that there’s more to the story here,” adds Gallagher. “You can’t just look at this story very quickly and make a judgment. You have to sit down and talk to all the people and see the story from different aspects.

“It’s not a feel good film, but it forces you to have empathy for things that you wouldn’t expect to have empathy for,” agrees Principe. “I think that’s a good thing.”

The filmmakers ultimately hope that the story provides a cautionary tale about thinking twice and reflecting critically upon the videos people see and share. If only empathy could go viral.