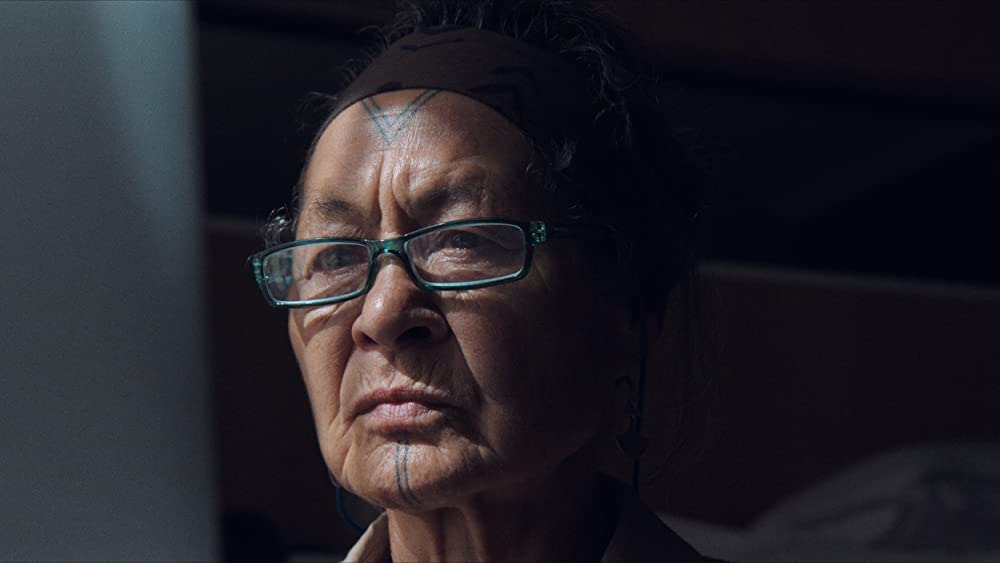

In 2016, the story of Aaju Peter and her fight for the seal hunt, wowed audiences with Angry Inuk. The film, directed by Alethea Arnaquq-Baril, whose story intertwined with Peter’s throughout Angry Inuk, won the Audience Award at Hot Docs and drew attention to the plight of Inuit communities to preserve a way of life that’s sustained them for generations. Peter’s story returns in Twice Colonized, which recently premiered in the World Cinema Documentary competition at Sundance.

Directed by Danish filmmaker Lin Alluna and produced by Arnaquq-Baril, along with Émile Hertling Péronard of Ánorâk Film, Stacey Aglok MacDonald of Red Marrow Media, and Bob Moore of EyeSteelFilm, Twice Colonized captures Peter’s fight for Inuit rights on a global scale. The film observes as Peter channels her anger into a book that aims to articulate the effects of colonialism across generations and borders. Peter reflects upon her experience as someone “twice colonized,” meaning that she faced the violence of colonialism once as a child in Greenland when the Danish government stripped away her language and culture. When she moved to the Canadian Arctic in the 1980s, she encountered a second layer of colonialism in a community grappling with its own hardships imposed by the settler state.

The powerful Twice Colonized follows Peter as she fights for future generations by advocating at the European Union and speaking with generations of young people eager to learn their nation’s past. Alluna also observes Peter’s daily life to understand the ongoing effects of colonialism in people’s lived experiences. Twice Colonized gets intimate access to Peter among the most vulnerable moments in her life, including her heartache when her son dies by suicide—a fate that reflects the urgent and immediate consequences of limiting communities ability to provide for themselves through means like the seal hunt. What resonates as clearly as it did in Angry Inuk, though, is Peter’s strength.

POV spoke with Peter, Alluna, and Arnaquq-Baril via Zoom as they attended the Sundance Film Festival.

POV: Pat Mullen

AP: Aaju Peter

LA: Lin Alluna

AAB: Alethea Arnaquq-Baril

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

POV: After appearing in films like Angry Inuk and Arctic Defenders, what made you decide to step in front of the camera and tell your story in a new film, Aaju?

AP: I think it was timely. It was important to tell the effects of colonization for me personally. I believe that other people who have gone through the same, and the colonizers themselves, needed to hear the story.

POV: Lin, what drew you to Aaju’s story?

LA: Being a white Danish person, I grew up with a history that I realized was false. I didn’t know that until I met Aaju by coincidence. I was flabbergasted by not knowing the history of my own country and not realizing my own path in colonization as a Danish person. After that first meeting, I wanted to find a way to share the knowledge that Aaju gave me. Two years later, we started filming together.

POV: Twice Colonized doesn’t shy away from the settler/Indigenous dynamic in the relationship between Lin and Aaju. How did you navigate that dynamic?

AAB: From moment I joined the team, we were all very honest, open, and keenly aware that Lin is from a colonial country that’s affected Aaju. We never ignored that or brushed it under the rug. Part of what we found interesting in this dynamic is that Aaju is always brutally honest, even to her best friends and people she loves dearly. She won’t shy away from the truth. People have shared experiences with Aaju’s life, but Aaju is uniquely able to confront hard truths, which makes this film possible. I also found it so interesting to see Lin’s desire to hold her own people, her own country, accountable for their actions through history to the present day.

POV: It’s interesting to see Aaju credited as a writer on the film, too, so what was Aaju’s role in shaping the story?

LA: We would talk about what to shoot, why to shoot, and when to shoot. It was a process of always being in dialogue about what this film is about and what we need to shoot to convey the story. That meant having flexibility during shoots to go with whatever felt right in the moment for Aaju and the journey that she’s on. In documentaries, you don’t have a script as in a fiction film, so having that collaboration where we talked about what and why to shoot is part of being a writer of a documentary film. People were skeptical about a collaboration where the protagonist had agency and a say in how to be portrayed, but it was important for this film that Aaju had a say in the story.

AP: It was much more complex than I imagined. I just lived my life, but all the things that were so amazing to me were edited away. Then you have the raw woman going through all the hardship. My view of my life is quite different because we all live this lie that we tell ourselves every day, all day long. It was good to see another person’s take on my life and how it’s touching other people.

LA: One of the things that attracted me to working with Aaju was that, from the first scene we shot, she was very personal. It was the scene where Aaju’s talking with her friend about how it feels to speak Danish. That was a personal entry point to colonization. At one point, Aaju said to me, “You can’t just film me on stage with all the success. You have to film behind the scenes—the battle that’s going on because of the effects of colonization.” As a white Danish person, we think that colonization happened a long time ago, and now it’s over.

AAB: As a documentary director myself, I know how much of the writing of a film is in the editing. Something that is probably unusual in this film is that Aaju is the subject but also had a very strong say in the edit. That was quite a balance to achieve because the film covers some difficult moments in Aaju’s life, perhaps the most difficult. We didn’t want to re-traumatize her by watching cuts over and over and over again. It was Aaju’s choice not to watch a thousand different cuts, but she did watch several versions of the film and, in the end, had final say over what gets cut and what doesn’t.

I remember the first time Aaju watched the film, she was initially very taken aback. You were upset about some things. When we sat down to discuss what Aaju wanted this film to say, she verbalized to us what she wanted this film to say to the world. The producing team realized at one point that Aaju is so incredibly hard on herself. She would watch one scene and understandably feel vulnerable whereas the rest of the world watches it and thinks, “My God, what an incredible woman.” It took a while for us to align how Aaju feels about seeing herself on screen and how the rest of the world is going to see her on screen. We see her as a hero, as a role model, as someone of incredible strength and insight into how we can all move through and out of colonization, and recover and empower each other.

POV: One thing that Angry Inuk talked about was the tone of anger among Inuit communities and how there’s a playful anger. Is that true across Inuit communities in different countries? How is the tone of anger different from one community to the next, or even from one film to the next?

AP: It’s very different because of the time of colonization. Greenland has been colonized for 300 years and has had a much longer time to forget the traditional Inuit practice of not showing anger in the way that Westerners do. When I moved to the Canadian Arctic, Inuit were just being moved into communities and still practiced the containment of anger where it’s okay for two-year-olds to show frustration, but a highly skilled person wouldn’t be showing their anger, waiting for the right time to talk about it.

POV: For Danes looking at Canada and then Canadians looking at Denmark, how do you think the two countries are doing when it comes to reconciliation? What can we learn from Denmark? What can Denmark learn from Canada?

LA: I think Denmark has a lot to learn from Canada. We are not as far as Canada when it comes to acknowledging our history and even thinking about reconciliation or apologizing. That’s a political issue in Denmark that people want to avoid. The film is going to be a conversation starter in Scandinavia for sure. Not only in Denmark, but in all of Scandinavia, we do not consider ourselves as colonizers. We do not think about our relationship with the Indigenous people that our politics affect.

AP: I always have to remind people that we have different colonizers at different points and that things have evolved at different speeds. The Danes, even though they developed infrastructure, they have a lot to learn from the Canadian examples as well, and the Canadian Arctic has a lot to learn. I’m hoping that this documentary of being twice colonized will get the conversation going. We are not the same.

AAB: Denmark is 20 to 30 years behind the conversation that Canada’s having right now about colonization. That said, I don’t want to let anyone off the hook. Canada has a lot of work to do. In Canada, we’ve benefited from the synergy between the Black civil rights movement in the ’60s and ’70s, and the American Indian movement at the time. Our people were coming out of the residential school experience and motivating each other to advocate and push back against colonization. We really benefited from advocacy in Black and First Nation communities in North America. For that reason, Canada’s started to confront these questions a bit sooner than Denmark. They have some catching up to do, but Canada’s not that much better.

POV: You mentioned synergy and I remember thinking about Aaju and Angry Inuk two years ago when there was news about the lobster fishing situation in Nova Scotia and conflict between the Mi’kmaq and the settler fishers. Has there been any synergy between what’s happened there to mobilize attention towards the seal hunt?

AP: It has been very difficult because it’s just me advocating for sealing and the right to sealing unless we get organizations and other people involved, and funding to do promotion and advocacy. I still have a full-time job to have money to advocate for our rights and our lives. I need much more support.

LA: In the film, Aaju is sharing her personal story, but also pointing us towards a better future. She’s saying that we need Indigenous people to have say in European politics. We need to find a way to establish a permanent forum for Indigenous issues at the EU. European legislation affects Indigenous land and Indigenous people outside of the EU, and that’s something that the EU needs to recognize.

AP: When I’ve gone to European Parliament to protest the anti-sealing campaign, Greenpeace, PETA, and other organizations that are promoting anti-sealing campaigns have offices there. They’re going to MPs every day year-round. We only go there a couple of days at a great expense. We already lost even before we start, so we need a strong voice in the European Union to advocate for our rights, not only just in sealing, but on all legislation that affects indigenous peoples.

AAB: What we see in the film about Aaju’s efforts around the permanent forum for Indigenous people at the EU, that’s the structural barrier that we came up against in Angry Inuk. As far as the Mi’kmaq lobster fishermen, of course there’s solidarity. We’ve never had an issue with solidarity among Indigenous people. But there’s not much those communities can do for us if we don’t have an avenue at the EU.

POV: How do you feel now that Canada has it first Inuk Governor General with Mary Simon? Have you seen progress for Indigenous issues since she stepped into the role?

AAB: I’ve seen some interesting commentary from other Indigenous groups in Canada who are upset that an Indigenous person would take that role and basically represent the Crown. Then I’ve seen many Inuit who are so proud of her taking that role and representing that we are citizens of Canada too. It’s important to highlight that there are many first Nations that do not consider themselves Canadian or do not consider themselves citizens of this country because they’re still occupied territories. Inuit are one of the nations that did choose to join this country, so we do consider ourselves citizens of Canada. Whether or not I personally am happy about that is beside the point. For many of us, as problematic as Canada is, we see it as part of our job as citizens of this country to make it a better country. We’re really proud to see Mary Simon in that role.

AP: Knowing Mary Simon before she become Governor General, it was right to choose her to represent Canada because somebody has to work within the establishment. Somebody has to represent and work towards all of Canadians, but also with her ability to speak Inuktitut, and her intimate knowledge with Greenlandic, Alaskan, and Siberian Inuit, she was the perfect voice, not confrontationally, but in the way, she speaks from her ancestors and joins everybody. My grandkids can look her and say, “I can be Governor General.” My granddaughter danced with the former Government General herself. So there’s hope for Canada.

AAB: It’s also important to mention that Mary Simon has been a badass resistor against the colonial government for her entire life. She doesn’t take that role lightly. We have to acknowledge that she doesn’t have a magic wand. She cannot solve all Indigenous issues in this country during her tenure, but it’s an important symbol for us. It’s highlighted structural issues, like the amount of criticism she received for not speaking French, for not speaking both colonial languages in this country when she wasn’t given the opportunity to learn them as a young person when the country attempted to steal away her Indigenous language. It highlights how much education still has to be done in this country around language.