On a sunny March day, Alanis Obomsawin sits in her office, talking about everything from future projects to enduring the 1990 crisis that pitted Mohawks against Quebec cops and the Canadian army, turning summery woodland into scenes from Apocalypse Now. Not only was the Abenaki native shaken emotionally by the experience that inspired her most potent film, Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance (1993), she had “an eye infection, a terrible cold, a sore throat, poison ivy, and poison oak. Can you imagine? I was a wreck.”

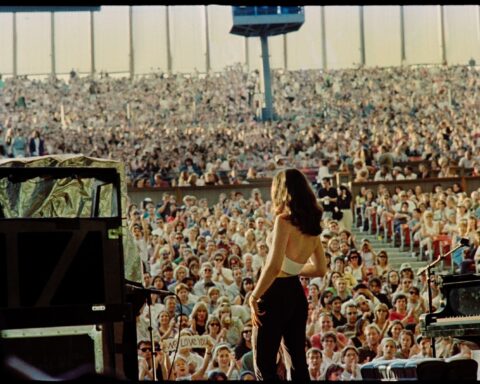

In her youth a model, singer, and regular on Montreal’s boho scene, where she met and befriended Leonard Cohen, Obomsawin is wearing a retro grey hat, black dress and stockings, silver jewelry and high-heeled pumps. She’s a striking woman, whose gravity can change abruptly into a radiantly playful smile you don’t often see in 76- year-olds. The National Film Board’s last staff director, Obomsawin has worked at the Board since 1967, generating project after project about Aboriginal people. When she’s not researching, or on a shoot, she travels frequently, lecturing and offering master classes, appearing at an array of events, and picking up honours like Hot Docs 2009’s Outstanding Achievement Award.

Within the tribute, the documentary festival organized a retrospective of Obomsawin’s work and the debut of her latest film, Professor Norman Cornett – “Since when do we divorce the right answer from an honest answer?,” which portrays a man she considers a brilliant teacher, and, like many of his admirers, was stunned when McGill University fired him. Showing no sign of a ho-hum attitude toward yet more praise for her work, Obomsawin says that she’s “very touched. It’s such an extraordinary festival.”

Apart from a couple of file cabinets and a work table spilling over with paper, Obomsawin’s workspace at NFB Montreal is crammed with posters, framed artwork, colourful fabrics, a rainbow-coloured, papiermâché fantasy beast, and a giant hoop with a feather dangling from it. The dream catcher was given to her in Burnt Church, New Brunswick, during the making of Is the Crown at War with Us?, a movie simmering with the tension of a situation that threatens to go out of control, and does.

The 2002 doc zeroes in on a dispute between Mi’gmaqs and non-natives over lobster fishing rights in Miramichi Bay. For the people of Esgenoopetitj, a 1752 treaty granted them “free liberty” to hunt and fish, exempt from costly governmentissued licenses. In summer 2000, their white neighbours threatened the natives and destroyed their traps. Even worse, officers of the DFO (Department of Fisheries and Oceans) harassed the Mi’gmaq to the point of ramming their boats and tumbling them into the sea. The film chronicles as hocking panoply of ass-kicking that cost Canadian taxpayers $15 million.

Like most of Obomsawin’s films, Crown flashes back to the history of European outsiders who put themselves in charge of territory inhabited by native people for thousands of years. Sometimes, they signed treaties that gave back a little land and granted certain rights. Then sooner or later, the British lords, the French seigneurs, the priests, and the modern day small town mayors would pull a fast one on the “savages.”

In her NFB office, Obomsawin leans forward, her eyes fixed in a dark gaze. “Any time there’s a problem,” she tells me, “any time you mention First Nation People, Native People, call us what you like, it always has to do with land and resources.” Despite laws and treaties, “the municipality next door has always found a way to take land.”

In contrast with the oppression and duplicity they expose, Obomsawin’s films evoke Indian life before the advent of Europeans in the New World. She montages idyllic paintings, archival photographs, and nature images into a reverie of a lost paradise where work was linked to land and water, and therefore spirit. Traditional language and prayers, songs and throbbing drums sustain people so marginalized, many have never seen beyond crude stereotypes of “Indians.” While connecting modern natives to their ancestry, Obomsawin also shows them as typically North American, relaxing in lawn chairs, playing softball, appearing in wedding portraits and family snapshots.

A director who records audio interviews with her subjects before she starts to film, docs à la Obomsawin play as much to the ear as they do to the eye. Wild sound of birds and insects thread through the films, subliminally reminding viewers that the people they’re watching either live close to nature, or yearn to reunite with it. When she was shooting her first film, Christmas at Moose Factory (1971), a portrait of a Cree village through children’s paintings, Obomsawin “took sound of the wind in many different places, even inside the residential school by the window because it was so weird. I’m fascinated by sound.” And there’s the melodious sound of Obomsawin’s voice. Her films would not be the same without the calm, measured narration that fuses with her matter-of-fact editing. Whatever the outrages she’s documenting, the tone of her movies never goes strident or resentful.

Born in New Hampshire, Obomsawin spent her early childhood in Odanak, the Abenaki village on Quebec’s St. Francis River that has inspired her throughout her life and career. After her initial explorations of native culture in filmstrips and docs like Mother of Many Children (1977), she turned uncompromisingly provocative with Incident at Restigouche (1984), and Richard Cardinal: Cry from a Diary of a Métis Child (1986), the sad story of a teenage boy who hung himself after years of oppressive institutionalization.

One of the Obomsawin titles that sounds like a western, Incident at Restigouche captures a showdown between Mi’gmaq fishermen and Sûreté du Quebéc cops in full riot gear. Triggered by government claims that the Indians were overfishing salmon, the conflict was too hot for the NFB to handle, and it balked. But Obomsawin fought for the film and won, just as years earlier she convinced Jean Chrétien to help her retrieve archival material a bureaucrat told her was lost.

Obomsawin’s confrontations peaked with Kanehsatake: 270 Years of Resistance, winner of 18 international awards. Her most vérité film tracks the drama of armed Mohawk warriors resisting a small town mayor’s plan to expand a golf course and build condos on land held sacred by the natives. For 78 days, Obomsawin filmed in the midst of an absurd situation that threatened to explode into all-out war when the Canadian army rolled in.

At night, Obomsawin recalls, the only illumination came from military spotlights sweeping the area, and every sound was nerve-wracking. She got into a futile argument with a Quebec cop that made her “feel like an empty chicken.” Another cop brought her flowers, and she thought, “There’s everything here,” including some locals who became so enraged when her cameraman filmed them, she rented a more secure room where she would less likely be attacked.

Obomsawin followed up Kanehsatake with three spinoffs that mix new material with footage from the original movie and material she reluctantly cut out of it. My Name is Kahentiiosta (1995) concerns a young Mohawk activist who got treated like a common criminal after the standoff, and “intrigued” Obomsawin because she “preferred to go to jail rather than give them another [non-native] name.” Spudwrench – Kahnawake Man (1997) focuses on Randy Horne, an ironworker beaten so badly during the crisis he could have died.

The final film, Rocks at Whiskey Trench (2000), like the other Kanehsatake docs available in a DVD Box-Set from the Film Board, travels to Kahnawake, the reserve whose activists supported fellow Mohawks with a blockade of Montreal’s busy Mercier Bridge. In August 1990, worried about a retaliation, natives drove 75 cars out of Kahnawake, carrying women, children, the elderly and the sick. Like something out of Night of the Living Dead, a mob of locals collected in the dusty wasteland of “Whiskey Trench” and threw heavy rocks at the convoy.

The film turned out to be a catharsis for the people who ran the gauntlet and for Obomsawin herself. When it was finished, she “felt free. I felt I’d done my duty.” Not only could she finally let go of the story, she now believes that despite the outrage of the military intervention, “the government was right when it sent in the army. Otherwise, it would have been just the police, and there was so much hate from them toward the Mohawks that we would have seen much more violence.”

In 2006, Obomsawin signalled a need to connect with roots in her film, Waban- Aki: People from Where the Sun Rises. The doc evokes the daily realities, charmed traditions, and mythology of her own tribe, considered descendents of the first people to see the sun’s light. Considering her own need to return, it’s fitting that Hot Docs chose to screen one of Obomsawin’s first shots at giving Aboriginals a chance to depict themselves, a re-mastered DVD version of the filmstrip Manawan 2 (1972).

During Obomsawin’s work on the Manawan project, natives in the region accepted Catholic priests’ version of their Atikamek language. “They twist, they do it their own way,” she says, “and they bring it back, telling you, ‘This is your language; this is how you speak. This is how you write. This is how you do things.’” But now, like other groups, the Manawan natives are inventing a written form “to their own sound, to the way they feel is right, not the outsider coming in. It’s fantastic.”

At 76, Obomsawin is circling back to her early focus on language, education, and children. “I want to make a series of short children’s films,” she tells me. “For me, children are the future, and I’m very comfortable with them. I want to do things that can guide them in life.” Despite all the darkness she has witnessed, Obomsawin believes that stories illuminate, and information redeems. If each province had educated native and non-native children about the tribes in its region, much grief could have been avoided. Bad information made natives “invisible and miserable”; the kinds of truths she conveys in her films have changed the attitudes of once hostile politicians and lawmen.

“You’re always feeling a lot of hate towards you,” Obomsawin says, “but I honestly feel that I love more than hate. And that’s how I can continue.”

“So I guess you’ll never stop,” I say.

“No.” And she laughs.