I’ve recently rejoined the board of the experimental media collective Pleasure Dome after a 30 year gap, and I’m grateful to find the fringe film scene filled with young people who seem interested in difficult movies for mysterious reasons. One of the odd things I’ve noticed is that whenever they say the word “film,” their faces get soft like Jello, their eyes glaze and even in spite of themselves their chin leads them towards a forgotten star on a lost horizon. Film. The response, which signals a nostalgia for a time they were too young to experience, is distinctly sexual, and it’s made me to start paying attention to what happens in the body when a super 8 or a 16mm emulsion is being received, or on the other hand when a digital file is being bounced off a screen and into our pores.

I believe that this is one of the secret projects of the book called John Porter’s CineScenes: Documentary Portraits of Alternative Film Scenes Toronto and Beyond 1978-2015, which is divided in two: the captioned analog black and white part, where faces and names can sing together, and the colour digital photography aftermath section, where the act of naming is deferred or displaced. All the photos are preceded by glowing essays about John Porter, a photographer and filmmaker, who has documented the fringe film scene in Toronto for 40 years.

One of the secrets that no one has to say out loud about fringe movies is that most of the time they are made by one person. Fringe films feature an extreme version of the auteur theory. When I flip through the pages of this handsome new book, I can’t help noticing that the faces responsible for making difficult films have also been heretical enough to create videos and other apostasies. There is an insistence in this page after page collection, that the bodies of these artists are engaged and reimagined by the machines that they use and which defines them.

Every portrait by John Porter is also a self portrait. It’s as if the photographer/filmmaker could only make a picture of his face by showing us the faces that are looking back at him. This is what every face in the book has in common: they are all looking at the photographer. They can’t seem to turn their faces away, as if they had arrived at the scene of an accident, unable to keep themselves from the catastrophe. The catastrophe of identity.

The photographer is not interested in the flow of life, the candid encounter, the summary gesture snipped out of the sequence. Instead, John Porter approaches his subjects like a fan. He begins by getting underneath them with his soft-spoken words and small camera, an optical instrument which he hopes will let them show what they are unable to admit, even to themselves. Before the picture is made, each person has a moment to compose their face as if they were already a picture, though as usual the camera is merciless in exposing the invisible worlds we all thought had been tucked away and tidied.

Here is a picture of Vincent Grenier, moments before a screening of his short formal films at the Funnel, a name attached both to an experimental film collective and their home made 100 seat movie theatre. One of Vincent’s movies is 20 minutes long filmed from an unmoving camera that shows the filmmaker leafing through a book, an atlas actually. It’s mostly abstract and silent and as I put my body into his body, I can feel his slumping anxiety at the prospect of sharing the longest 20 minutes in cinema history.

At the Funnel, where John Porter plied his craft as a photographer while exhibiting a visual onslaught of Super 8 films in the 1970s and ‘80s, it was obvious that words had refused certain members, but pictures offered a second chance to express some of those uncaptioned emotions. In general, there wasn’t a lot of talking in the movies shown at the Funnel: there wasn’t a rule about it or anything, but the theatre was a place for looking most of all. If you had to use words, the unspoken feeling was that you weren’t quite a filmmaker. Real artists could shoot a face with so much light in it you wouldn’t need the words.

Here is Peter Gidal. He was an American who had gone to England to spread his version of cine-puritanism. Faces and bodies shouldn’t be shown on film, he argued. The cinema’s identification with bodies was only the rebooting of fascism, according to this prolific structural-materialist manifesto writer. I love the way John shoots him here, up against a wall, the last man sitting, his legs folded as if he were turning away from the whole project of picture making.

Here is a snapshot of filmmaker Midi Onodera, the Funnel’s second equipment manager. I think she was the first person to show me what a computer was, and what it could do, at a time, when it was basically a typewriter without the need for correction strips. In this picture, she offers her face in a smile, but not the kind that follows the telling of a particularly excellent joke. I remember her deep, baritone-inflected laughter cutting through the sometimes awkward scrums in the Funnel’s lobby/gallery/beer parlour. But here her face suggests something more complicated than laughter. Perhaps it’s only my projection, but I think her face shows some of the tensions of an organisation that always seemed busy sawing off its own branches.

Here is a photo of the legendary American performance artist and filmmaker Carolee Schneemann at the Funnel, where she is setting up for her epic home movie Kitch’s Last Meal. Carolee was tight with her cats, and made a pact that she would shoot until her fave cat familiar Kitch keeled over and died. But Kitch lived on and on and the movie ballooned. Not only did her film run anywhere from two to five hours long, it required two super 8 projectors running at the same time. Carolee’s excellent movies were casual deliriums that turned everyday encounters into beautifully rendered arenas of seeing and discovery. So it’s interesting to see this portrait where her face is set slightly back from where it would rest naturally, as if she were literally taken aback, and you can see the strain of her holding her face like this in her neck and clavicle. How did all that let-it-all-hang-out looseness come from that tight face? The words I want to put in her mouth are saying: “what the fuck are you doing with that little thing in your hand, buddy? Get your little thing out of my face.”

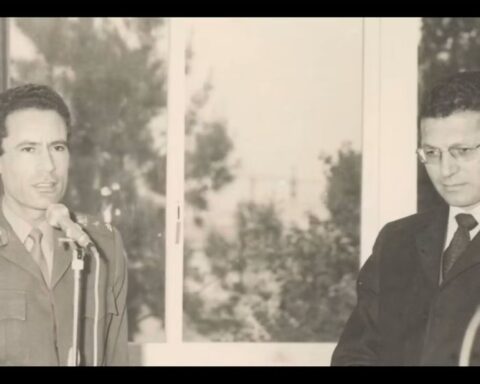

A final picture, a final recollection. Oh look, it’s P. Adams Sitney, author of Visionary Film, the bible of avant-garde cinema. He’s come north to show Hollis Frampton’s Nostalgia and Owen Land’s Remedial Reading Comprehension, and then to talk about them, to offer suggestions about what these movies might possibly mean. He wasn’t the only person ever to arrive at the Funnel in a suit; the gentleman who gazes so lovingly at him from just a few feet away, Bruce Elder, was one of the organisation’s original members and usually came in a jacket and tie. There are two people in this photo who are presenting for the camera. The first is Mr. Sitney who has winningly exhaled his cigarette at the decisive moment in order to keep the most important part of his face for himself, and the other is Funnel founder Ross McLaren who lifts his chin in his best Sid Vicious impression. But then there’s Anna Gronau, the director of the Funnel at the time. In this pic, she is in the shadows, with her eyes closed, the only woman in the boy’s club, all of them stuck in a corner, cornered again by each other. Anna’s hands are clenched and tight, knitting and unknitting stories like Penelope before the suitors, waiting for her day to come.

There have been rumours about a John Porter photo book for nearly as long as he has been making pictures. Kudos to editor/producer Clint Enns for making this project happen since part of the strength of John’s pictures comes from the fact that they were never made so they could be seen in a book. His photos are part of an ongoing process, the continual appearing and disappearing, opening and closing of bodies in a community.

John Porter’s CineScenes: Documentary Portraits of Alternative Film Scenes Toronto and Beyond 1978 – 2015 is published by the 8fest.