Twenty years ago, Peru was a no-man’s-land for homespun documentaries, a country reeling from an internal civil war, economic meltdown and a dictatorship that resembled a cross between a drug cartel, the agents in The Matrix and Mr. Bean. The president was clumsy and liked to dress up in funny outfits with silly hats, but he also had a penchant for corruption and secret death squads and turned the country’s media into his own personal PR team.

In this climate of fear and censorship, a handful of 20-somethings decided to form an association of independent filmmakers. They had no formal education, little training and no equipment or funds; people said they were either crazy or brave (they were both).

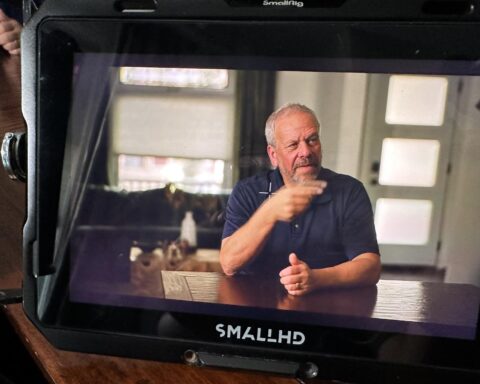

The troupe was encouraged by Stefan Kaspar, a Swiss filmmaker who had been living in Peru since the late ’70s and was even crazier and braver than his protegés. Stefan gave the young dreamers a room in his house, lent them equipment and provided advice and training. He had a good deal of knowledge to impart; Stefan was one of the founding members of Grupo Chaski, a Peruvian film collective formed in the early ’80s that had developed its own revolutionary style.

Chaski’s subject matter and treatment were radical for the time. Their first film, Ms Universe in Peru (1982), juxtaposes glitzy scenes of international beauty contestants with the harsh reality facing poor urban women and peasant farmers. It is the stuff of dark comedy: a line of buxom white “Misses,” smiles aglow in bathing suits outside Lima’s sombre colonial government palace, contrasted with potato farmers from the mountains carrying toddlers wrapped in bright shawls on their backs.

But Chaski didn’t portray their Peruvian farmers as victims; the faces on the screen are determined, questioning, often angry, and their impassioned declarations show they are more than aware of the pageant’s hypocrisy.

Other Chaski films include Gregorio (1984) and Juliana (1989), two features about street kids that blend documentary and fiction, using children from poor neighbourhoods as actors. Both movies did well on the international scene— Juliana won the UNICEF award at the Berlinale—but their success at home was the real surprise. For the first time Peruvians stood in line en masse to watch films about their own reality, with more than a million theatregoers for Gregorio, and 7.5 million viewers on national television.

“Film doesn’t change reality,” said Stefan, “but it has the potential to include the excluded, to visualize the invisible, to remember the forgotten, to give images and words to those who do not have them.”

Sadly, Chaski broke up in 1991 and remained dormant for over a decade. But in those dark times before YouTube and pirated DVDs, Chaski’s archives served as inspiration and training for the young Guarangos.

There was also an organic link between the groups. Marino Leon, the kid who played Gregorio in the movie, left the streets to grow up under Stefan’s roof and became one of the founding members of the new association. It was Marino who gave the group its name, “Guarango,” a native tree from Peru’s coastal desert that survives on scarce resources by digging its roots deep into the soil and remaining small but tough.

It would take some time, however, for the group to develop those deep roots.

Their greatest obstacle was a lack of funds. ‘Funding trouble’ in Peru has a much more pervasive meaning than it does for most Canadian filmmakers. It means borrowing bus fare from your sister to make it to the office, not having a cent to your name and no access to credit empty pockets, flat broke, bumming cigarettes.

Everyone wanted to direct, but no one wanted the inglorious task of finding the money—no one except Ernesto (Tito) Cabellos, a painfully shy young man who didn’t consider himself an artist but stepped forward to be the group’s producer. Stefan taught Tito how to write a budget and he began getting small projects: music videos for Peruvian bands, video workshops with kids and short promos for companies and non-profits.

Budgets were tight, profits were nil and the work wasn’t going to land them a slot at Cannes in the near future. One by one, the gang dropped out until only Tito was left.

When crisis hits in Latin America, your family steps in to help. Tito and his brother Rafo drove their father’s old Volkswagen Beetle around the chaotic streets of Lima as a cab to raise money for basic equipment, and their younger brother, Ricardo, taught himself how to edit and build computers out of second-hand parts.

With Chaski dormant, Stefan was in serious economic trouble, and Guarango moved from his house by the sea into an apartment in an ocean of concrete blocks designed by a somber East German architect. The Cabellos brothers were behind in rent, the phone was often cut off, and if Mom hadn’t stepped in to make lunch every day, they would have been hungry as well.

Around this time, one day in 1997, a bright-eyed young Canadian girl named Stephanie showed up to do an English voice-over for a Guarango video. She had just arrived in Peru to work at a human-rights publication. Every day she sat at her desk in a posh colonial house and edited articles about thrilling, often dangerous happenings that seemed very far away: the Zapatistas in Mexico, the peace movement in Colombia, the mothers and grandmothers of disappeared children in Argentina. Her job was safe, the pay was reasonable with health benefits and good contacts; she was invited to a lot of embassy parties with Very Important People.

After she finished her voice-over, Tito told her about his dream to make independent documentaries about what was really happening in Peru, outside the upper-class neighbourhoods of Lima; or, in the words of Chilean filmmaker Patricio Guzman, to add a page to the country’s photo album. She looked at Tito’s bare office with its faded paint, the patched-up computer and dented microphone and thought his cause was hopeless and perhaps even insane.

So she did what any idealistic young woman would do in her place. She (that would be “I”) fell in love with the dream and the dreamer and joined the crew.

We decided to make a series about Peruvians standing up to foreign mining companies. It seemed a perfect combination: a Canadian, angry and embarrassed at the way her countrymen were exploiting Peru’s natural resources, and a Peruvian who wanted development, but how and at what cost?

No one was talking about mining issues back then. Human rights groups said it was an “environmental issue” and wouldn’t get involved, perhaps forgetting that humans need a clean, safe environment to survive, and the media ignored anything critical of business interests. But on the ground the situation was about to boil over—people were fed up and angry; they wanted to tell their story.

We wrote up a modest proposal. The series would take 18 months, six months per film. The year was 1999. We had no funds, no equipment, no experience directing or making independent films and no idea what we were getting into.

Eleven years later, we finished the third film in the series…. Okay, it took a bit longer than planned, but the three films have been seen around the world in over 150 film festivals, on television in North America, Europe, Latin America, Asia and the Middle East and have won more than 30 awards and recognitions.

I hope it’s a case of the tortoise winning the race in the end, or at least having a hell of a ride along the way.

Influenced by Chaski’s experience in the ’80s, we carted the films around Peru with a digital projector, a large swath of heavy fabric for a screen and speakers. Sometimes we had to hunt down fuel to get the local generator up and running in places without electricity.

Shortly after our first film came out, Stefan resuscitated Chaski and launched a Micro Cine project that helped expand our reach. Our ally screened the films in more than 50 community-run theatres in rural areas and poor urban neighbourhoods in Peru and eventually in Bolivia and Ecuador as well. Another group, called “Nomads,” incorporated our mining series into their roaming film project, travelling around the country with a portable theatre.

Peru is a haven for cheap, pirated DVDs so we made more than 3,000 copies of our films and gave them to educators, activists and anyone willing to get a bunch of people together to watch. We also gave master copies and posters to our favourite black market stalls in Lima so they’d list us beside Hollywood blockbusters and other titles. Don’t get me wrong, I’m against piracy in countries where people can pay for original DVDs. But when we started, poverty was running at 50 per cent in Peru, and this sizeable group happened to be one of our target audiences. So we made the controversial decision to make piracy part of our distribution plan.

We were overwhelmed by requests from people in other mining communities who wanted us to film their struggles. Faced with the annoying human shortcoming of only being able to be in one place at a time, we looked around for more partners. Our sound designer and editorial consultant, Jose Balado, was forming a new group called DocuPeru.

If we were idealistic and crazy, they were off the map. Jose, a charismatic film professor from Puerto Rico, and his small army of Peruvian film school graduates were travelling to isolated parts of the country, giving free production workshops to ordinary people who had never used film. They called this wild circus the “Documentary Caravan.” Workshop groups produced their own short docs, which were screened in their communities and at a yearly festival in Lima.

Jose’s goal was to make film accessible to all Peruvians. This was DocuPeru’s activism, and it was admirable. But what if they took their Caravan to communities standing up to powerful foreign mining corporations and became eco-film warriors?

Luckily Jose was bold and political enough to take the risk. We sent DocuPeru off to work with farmers and activists who were standing up to South America’s largest gold mine, owned by a U.S. company. After the training, some of the participants realised they were the victims of a spy operation: strangers were photographing and filming their every move. They devised a counter-espionage operation, turning the cameras on their aggressors. You film me; I film you filming me.

It may sound comic, but the soundtrack was chilling. The activists and their families received threatening phone calls—a female lawyer was told she would be raped and killed, her body cut into pieces and eaten by dogs.

When one of their allies was assassinated, the activists’ leader, a Peruvian priest, upped the stakes and caught one of the spies, along with a copy of his computer hard drive containing hundreds of reports, photos and video footage of the activists. The spies had given the activists nicknames that read like a bad parody of a Hollywood thriller: “Four-Eyes,” “Roadrunner,” “Yoda” and “Goose.” Their main target, the priest, was simply “The Devil.”

I was giving a filmmaking workshop with the activists when Father Marco captured the spy and remember working alone in his office late at night and jumping every time the phone rang or someone knocked at the door. The filmmaker had become a subject, and the protagonists had become filmmakers; we used the activists’ footage to make The Devil Operation, the final movie in our mining series, which opened at Hot Docs in 2010.

Now Tito is about to release the fourth film in the ever-expanding trilogy, about women farmers struggling to protect their sacred lakes from mining. With such a lengthy series, new faces have had to step in to fill big gaps. Tito’s long-time mentor Stefan Kaspar passed away suddenly last October while filming in Colombia. A month later, another key supporter and advisor left this world: Canadian doc giant Peter Wintonick.

When you’re thrown up against the fragility of life twice in one month, and two great influences are suddenly and painfully gone, you grieve, you mourn, you pay homage. And once the pain starts to lessen, you realise that maybe it’s time to celebrate making it to 20 years and get everyone left together while you still can.

So, this past May, Guarango held six nights of free screenings, panel discussions and workshops in Lima, opening with an evening devoted to Stefan and Grupo Chaski’s films.

The panel discussions leaned toward storytelling. Tito remembered how a volunteer from Stefan’s Micro Cines project in the southern Andes complained about the length of our second film.

“It’s a good movie but the screenings take more than three hours,” he said.

“Three hours?” said Tito. “But the film is only 86 minutes long.”

“Yes, but every 10 minutes I have to press ‘pause’ and explain what happened in Quechua,” said the volunteer.

Tito thanked the translator for his patience, and from then on we included “Quechua dubbing” into our budgets.

This turned into an unexpected adventure of its own. Despite the fact that Quechua is spoken by millions of Peruvians, especially in the southern mountains, there are no professional dubbing operations and for our last film we had to train radio actors from a nonprofit to do the translation and voiceovers. One incredible young woman pulled off every secondary female character, from a frightened activist to an angry lawyer and an elderly grandmother in mourning, with tears streaming down her face in the sound booth.

Not all our memories were so positive. Godofredo Garcia, a mango farmer who led the opposition against a Canadian mining company in his lush valley, was assassinated before we’d filmed a good interview with him. This was a grim lesson. Never wait to film an environmental defender in Peru; you can’t count on them being around tomorrow.

There were also parts of our history that were edited out, deemed unsightly for the public. We didn’t mention that our own devils nearly derailed the last film in our mining series. Tito and I separated while finishing the second film, but our breakup was so amicable, attending festivals and press events together, we thought we could still co-direct. Tensions erupted once production got under way on the new film.

Without getting into the mean and nasty, we both said and did things we’d rather forget. It seemed we were human, after all. The project was at risk of spontaneously combusting when Peter Wintonick convinced us that the film—and the serious human rights abuses it exposed—was more important than our squabbles. Tito decided to concentrate on Cooking Up Dreams, a solo project, which was nearing completion, and I directed The Devil Operation alone, with Tito as executive producer and consulting editor.

Both films went on to win international awards and play at top festivals, and we healed our friendship by proving we could direct on our own and move on with our lives.

This hidden story, of overcoming pride and jealousy and putting the cause of justice before our own egos, is as real and vital to Guarango’s story as the official timeline painted on the wall outside the anniversary screenings. But perhaps it’s too complicated to explain in point-form bullets or during a panel discussion in front of an audience of strangers.

So it became like one of those key events the cinematographer failed to capture on film: You know it’s important, but you just don’t have the material to include it in the final cut.

At the closing party, in the elegant cultural centre run by the Spanish government, the wine ran out too soon and the food even sooner, so we ended up at an old canteen in Lima’s run-down centre.

Queirolo is stark and dusty, lit by bare fluorescent bulbs and crammed with small wooden tables and hard chairs. Cracked tiles cover the floor and bottles of cheap pisco, rum, beer and wine line the brown shelves running up the walls to the ceiling.

The décor hasn’t changed in at least 50 years; neither have the waiters, crinkled and wizened, still rushing through the drunken crowd with trays of ham and cheese sandwiches, pig’s feet and fried bull testicles and other coastal delicacies. The place smells of booze and sweat, pickled olives and cheese. Tender Criollo ballads play beneath the crowd’s heated talk and laughter.

This is where I first met Peruvians resisting corruption and abuse of power.

Seventeen years ago, students, activists and even regular citizens began to rise up against Alberto Fujimori, the homicidal Mr. Bean president mentioned at the beginning of this article. Street protests were met with violent repression. Clouds of tear gas, police batons and heavy riot shields would scatter the crowd, but the keeners would meet up afterward at Queirolo, red-eyed and dizzy from the fumes, brandishing torn posters and placards, comparing scrapes and wounds and planning the next campaign.

We drank beer from the same glass, passing it around the table in a kind of solidarity of saliva, and the windowless place filled up with smoke (you could still poison yourself and others in public back then).

Later, when the place closed for the night, we’d move to an empty room across the road, instruments would come out and there was singing and dancing.

Now, looking around the crowded tavern, the place is so unchanged I can almost see the ghosts of those idealistic youth. It could be 1982, with a young Stefan Kaspar and the rest of Grupo Chaski in a corner, debating how to sneak their cameras into the Miss Universe contest. Or 1994, with Tito, Marino and the other young Guarangos, dreaming about the films they want to make. Even my younger self is here, with Tito and his brother Rafo, plotting how to get our first film past the Peruvian censors.

But tonight is 2014, and I’m here with Tito, his wife Susana and the small production team for his new film. There’s also Malu, Tito’s sister and filmmaker, and Fabricio, the editor of my last film and co-founder of Quisca, our film collective in the mountains.

After 20 years of struggling, learning, screwing up, laughing, fighting, winning, losing and waking up in the middle of the night with the cold sweat of fear, we’re still here, ordering tamales and bottles of warm beer, remembering the past and stumbling along with new projects.

That twisted little tree from Peru’s desert coast doesn’t grow very big, but it’s a survivor.

And that in itself seems worth celebrating.