Somewhere, in Pisba, Colombia, filmmaker Pablo Álvarez Mesa and his sound recordist/partner Erin Ryan peruse the high-altitude grassland. Inhabited by the Muisca people, the region’s unforgiving landscape carries an important history. 200 years before the team roamed the Andes with their Bolex, Simón Bolívar’s liberator militia traversed the same mountains and verdant marshland. Bolívar fought to free the Indigenous people of Colombia from the clutches of the Spanish government. However, his liberation campaign came at a great cost. Hundreds of soldiers died from malnutrition and hypothermia on their journey. Their bodies were dumped in a nearby lagoon, which serves as the basis for Álvarez Mesa’s Colombian-Canadian documentary The Soldier’s Lagoon.

500 kilometres west of Pisba, in Antioquia, a team from the Dominican Republic diligently recreates the history of Pablo Escobar’s reign of terror. Escobar, a notorious drug lord from Medellín, infamously imported animals from Africa for his own amusement. His reckless acts culminated in the merciless murder of a hippopotamus. Pepe, directed by Nelson Carlo de los Santos Arias, derives its name from the slaughtered megaherbivore and contextualises the tragic tale. As with The Soldier’s Lagoon, Pepe reclaims the violent history of the region by giving voice to the casualties of their colonial pasts.

In early 2024, these productions premiered at Cinéma du Réel and the Berlinale, respectively. Screening just one month apart, both films garnered international acclaim. Pepe won the best director prize within the main competition at the Berlinale. The Soldier’s Lagoon would later win the best Canadian feature documentary award at Hot Docs. Both films were shot in Colombia, where they contrast one another through their unique interrogations of the land and its history.

The Soldier’s Lagoon continues Álvarez Mesa’s exploration of Bolívar’s liberation campaign, which began with Bicentenario (2020). The film is the second part of a planned trilogy that details Bolívar’s turbulent journey. Capturing the voices of the Indigenous residents, the unconventional documentary contrasts their testimonials with the realities of present-day colonisation. During the interviews, Álvarez Mesa avoids filming the speakers’ faces. Instead, he focuses on their footsteps and hands. The approach emphasizes natural gestures, while demonstrating the relationship between the human body and the Pisba region.

Pepe, meanwhile, revitalises the tragic tale of the unhappy hippo, who was killed by hunters after Escobar had died. As an artist from the Dominican Republic, Arias recognised the similarities of the hippo’s tale with the colonial migration of slaves between Africa and the Americas. Through the personification of the titular character, the story asks big questions regarding Colombia’s colonial past with a playful approach. While balancing the hippopotamus hijinks, Pepe retells a timeless story about a powerful dictator and his cataclysmic greed. Through sentient narration, Arias commissioned voice-actors to personify the ghost of Pepe.

Notably, both filmmakers shot on location. With The Soldier’s Lagoon, the two-person team took structural inspiration from the history of the land. “The film’s rigour stems from the path that Bolívar took,” Álvarez Mesa tells POV. “In terms of the shots, that is the guiding principle of the structure. Within that, I’m looking for variety in the composition of the landscape. I wanted to express the dynamic and complex páramo ecosystem.”

Meanwhile, Arias shot Pepe in Antioquia, the state where the real-life hippopotamus hunt took place. However, Arias couldn’t shoot in the municipality of Puerto Triunfo, the precise location where Pepe was slaughtered. Instead, the team opted for Estación Cocorná, a township by the Magdalena River. Arias says he chose the location due to the residency of a neighbourly hippopotamus. “If I want to make this film, it’s not about the location,” says Arias. “I really needed a hippo that was alone. Otherwise, how was I going to make Pepe?”

Both productions include 16mm footage to demonstrate the scope of their depicted regions. Álvarez Mesa explained that, unlike digital, the use of celluloid highlights the apparitions, obscurities, and layers of exposure in the frame. The team used tungsten light film over daylight stock due to the blue tint that naturally develops with the exposed image. The blueish images are associated with the large bodies of water within the region. The colours are a reflection of the land and the country’s identity with the manipulated images evoking the ghosts of the past that reside in the landscape. With each entry in his trilogy, the films embody a specific colour from the Colombian flag. The Soldier’s Lagoon favours the second bar from the flag’s yellow, blue, and red triptych. “While the colours of nature seem natural, they are manipulated,” he explains. “The film stock itself has its own interpretation of those colours.”

On the other hand, Arias incorporates different formats of artistic expression. Unlike The Soldier’s Lagoon, Pepe doesn’t exclusively feature 16mm cinematography. Instead, RED cameras, discontinued Blackmagics, night-vision surveillance footage, and animation intertwine with the celluloid images. The same applies with the film’s off kilter structure. Arias includes narrative vignettes involving domestic disputes and incompetent authorities. His innovative potpourri personifies the perceptions of the community while spotlighting Antioquia’s underdeveloped infrastructure.

While Pepe casually oscillates between documentary and historical fiction, Arias rejects the label of “hybrid” form. He doesn’t believe in western labels and categorisations. Arias describes his artistic process as a constant digestion of the world through images and sounds. The dismissal of western classifications complements his form. “Storytelling is not colonised by a certain idea,” says Arias. “I feel like I have trained myself to not think like that.”

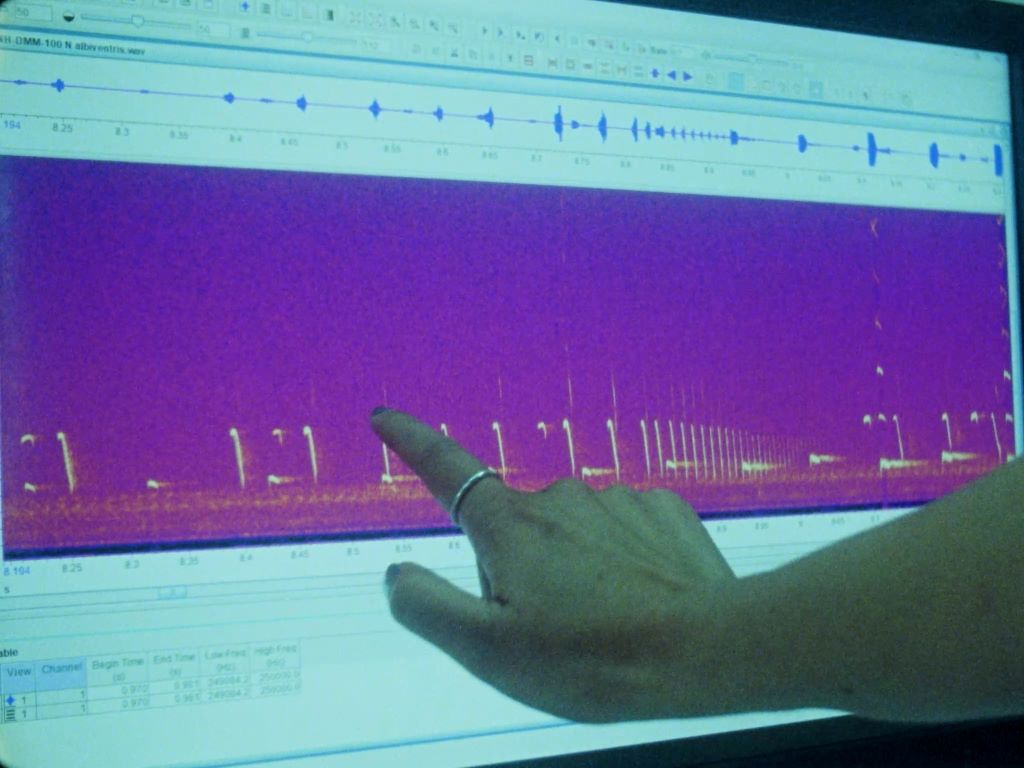

As for the sound design, Álvarez Mesa’s small-scale production balances location sound and archival sound within the final mix. A significant portion of the archival material stems from the thousands of sounds housed in the Humboldt Institute in Colombia. The library included sounds of birds from the state’s diverse regions. Incorporating the recordings of the past with the ambience of the present, Álvarez Mesa encourages the viewer to confront their relationship with nature and history and participate in the film’s immerse portrait of the landscape. “All of these different choices, whether it be film stock or camera movement, deal with the notion of a fluid imaginary in the history of storytelling,” says Álvarez Mesa.

Arias notably worked with sound director Nahuel Palenque, who installed different microphone setups on location to document the region’s natural ambience. Pepe features recorded sound effects, dialogue, and additional ambiences in 6.1 surround sound. Arias compares Palenque’s approach to a sound installation. In some locations, the sound team equipped 12 unique microphones to simultaneously document the reverberations of the region. In tandem with the locations, Pepe’s rich collection of sounds are authentic to its period-accurate storytelling.

Through their unique depictions of Colombian history, The Soldier’s Lagoon and Pepe effectively open new doorways for viewers to engage with their post-colonial storytelling. More relevantly, both films utilise a ghost story framework to haunt their colonial history. At the end of Álvarez Mesa’s documentary, the film drowns the viewer within the titular lagoon through a suffocating eight-minute sequence. As the camera sinks to the bottom of the gravesite, the Bolex captures phantasmagoric artifacts around the fallen soldiers. The Soldier’s Lagoon slowly dissolves into darkness.

At the end of Pepe, Arias hovers his camera over the hippo’s brutalised body. The viewer only bears witness to the aftermath of the killing. With the vertical movement, the final shot slowly floats over the hippopotamus as the voice of Pepe narrates the atrocity. A gentle pan unveils the vastness of Antioquia, as the anthropomorphised dialogue haunts the region. The ghost speaks to the spectator. “Everything is constantly related,” says Pepe. “Banishing the very idea of an annihilating transparency which, like a curse, does not stop repeating the same story.”