A passion project for Black British film director and video artist Steve McQueen, Mangrove is the first part of Small Axe, a five-part mini-series about the lives of immigrants from the Caribbean, who moved to England after the second World War, and learned to adjust to the racism and class system in their imperial motherland. The longest of the Small Axe films, Mangrove was due to launch at Cannes but had to wait to premiere at this fall’s New York Film Festival due to COVID concerns. Funded in the main by the BBC and Amazon Film Studio, the films validate the history of Blacks in Britain as told by McQueen, whose Oscar-winning 12 Years a Slave took him from being a key figure in the art world to international fame as a film director.

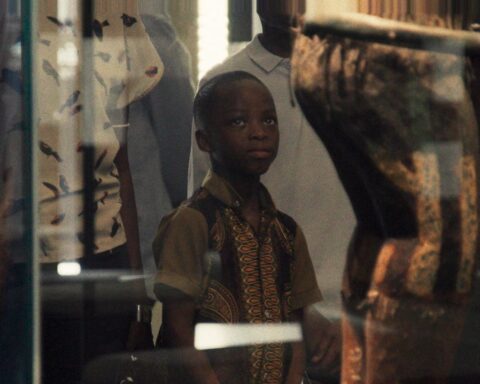

For the first film in Small Axe, McQueen decided to dramatize the first key legal case involving Black British people, that of the Mangrove 9 in 1970. Set in West London’s Notting Hill district, the Mangrove was one of the first successful Caribbean restaurants, offering spicy food in a convivial atmosphere where people could speak, eat and drink freely. Owner Frank Crichlow soon found himself and his restaurant attacked by the local police, in particular the racist Constable Frank Pulley. Raided constantly for drug violations—none of which were found on the premises—the harassment repeatedly took place in 1969 and 1970. Crichlow was supported by the local population, but his most notable advocates were the controversial and radical Black Panthers, who were led by Altheia Jones-LeCointe, her then-partner Darcus Howe and Barbara Beese. In August 1970, the neighbourhood launched a protest against the police, leading to a riot, in which a number of local Blacks were arrested.

The 9, which included Crichlow and Rhodan Gordon, a friend of McQueen’s father and the three Panthers, were charged with incitement to riot but the case was thrown out of court by the local magistrate, who found the police to have racist attitudes towards Notting Hill Blacks. Not to be outdone, the director of Public Prosecutions ordered them to be re-arrested on charges of riot and affray.

At this point, the trial of Mangrove 9 becomes the focus of McQueen’s film. In the first half, the narrative invites one into a casual intimacy, with the new British Blacks eating, dancing, drinking and engaging in bright conversations—particularly the Panthers. Reggae music is heard and you can practically smell the food as it’s being delivered to tables at the Mangrove. McQueen approaches the fateful demo through a slow build-up, which quickly escalates as the Blacks find themselves crushed into each other by police on either end of the parade. The camera locks in on some of the nine, particularly the women, as panic begins to ensue in the crowd. It’s a bravura, quite physical, scene and a true tour-de-force for McQueen.

As the trial unfolds, McQueen’s approach changes. He focuses on Jones-LeCointe, Howe and the rest of the 9’s lawyer Ian Macdonald, who get to speak against the prosecuting lawyers and to the judge, a white upper-class prig, who nonetheless begins to understand their arguments during the 55 days of the trial. A major coup for the 9 was deciding to have Jones-LeCointe and Howe to represent themselves, which allows more questions to be asked than would have been allowed Macdonald if he had defended everybody.

During the trial, Macdonald and Jones LaCointe and Howe got to make a case for an all-Black jury (based on the Magna Carta), introduce the phrase “Black power” into the trial and were able to establish, at least partially, the racism of the police. In the end, the 9 were judged innocent of their major charges, a major victory for the Black British not only in Notting Hill but throughout England.

A documentary available on YouTube entitled The Mangrove Nine, directed by notable radical Franco Rosso and scripted by the first major Black publisher John LaRose, makes fascinating viewing after seeing McQueen’s film. The casting by McQueen is meticulous: the 9 look, speak and dress like the real defendants at the trial. Even an excerpt from the Rosso/La Rose doc confers authenticity on the new Mangrove. Steve McQueen has made a terrific film—truthful, dramatic and truly important if one wants to understand the cultural and political changes that took place in Britain when Blacks genuinely joined their society