Apollo 11 is an immense achievement, a work of scope and ambition that is as thrilling and cinematically captivating as the latest blockbuster. Granted a run on IMAX screens before its mainstream release, the film is a celebration not only of the mission to the moon but the sheer magnitude of the project itself and the myriad of persons behind the three at the tip of the Saturn V. POV’s Pat Mullen’s fine review called it “Herculean,” and my Sundance take on it makes the case for this landmark film.

Todd Douglas Miller has assembled a team that may not rival the Apollo project in scope but matched its intent, shepherding a massive number of parts into a coherent, concise work that succeeds despite the many obvious pitfalls it needed to overcome.

In this exclusive conversation with POV, Miller discusses the film’s origins, the task of getting all that footage tamed, the many works that influenced the film, and how surprise discoveries of rare footage helped make this one of the more glorious, cinematic documentaries you’re ever likely to experience—Jason Gorber.

POV: Jason Gorber

Miller: Todd Douglas Miller

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

POV: I understand the Apollo 11 project began in part based on shorter film about another lunar mission.

Miller: The short film was called Last Steps [about] Apollo 17. The team that we assembled for the short film all work together now. I first interacted with Stephen Slater, my archive producer based out of the UK, on this. It started as just an editing exercise, playing with structure and form and seeing if we could tell [the story] only through archival footage.

POV: A project like this, where there are thousands of hours of audio and visual material, must be daunting in itself, let alone finding a way to tell the story in a fresh way. Where did you start?

Miller: There is a nine-day version of this film in our edit system!

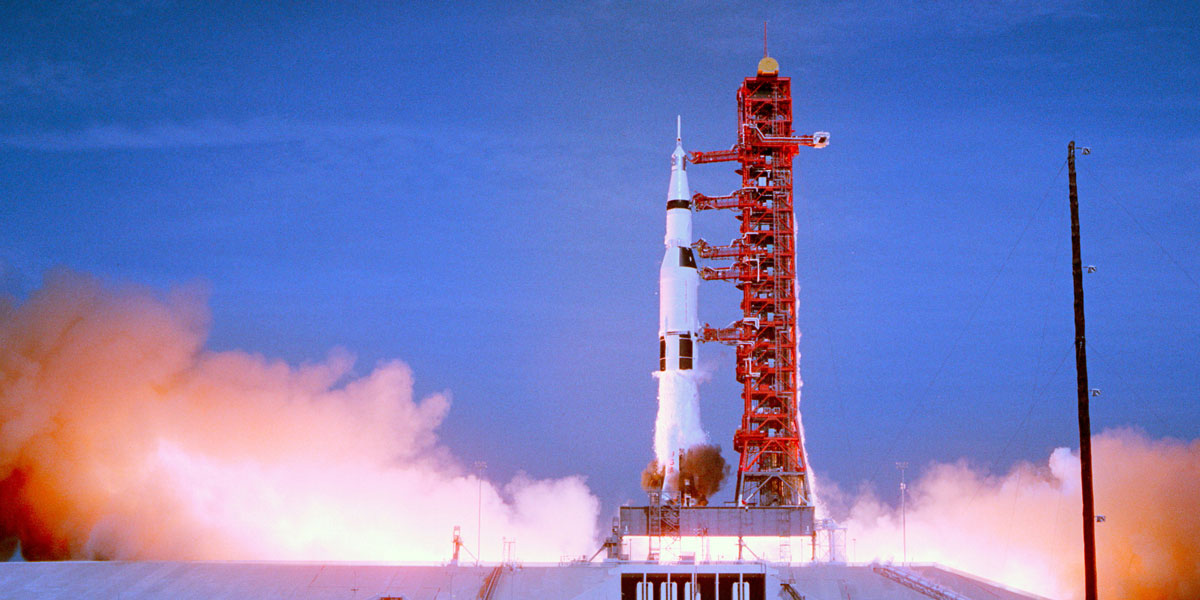

A lot of the footage we had involved training and some post-flight activities, but we just dismissed that. We looked at every available flavour of film format. For audio, we have the sound from the mission control, the on-board, the air-to-ground transmissions, and even things like news broadcasts. Walter Cronkite was giving a blow-by-blow in real time of the entire mission. We laid all of that out into a timeline and then identified what the big key moments were. A big resource for us was the transcripts that had been cultivated and curated by various volunteers working with and for NASA. Then along came the discovery of the large format material, which of course took everyone by surprise.

POV: Tell me the story of finding the 70mm footage.

Miller: We approached [the U.S.} National Archives and NASA [National Aeronautics and Space Administration] very early on with the intention of rescanning all of the available 16mm and 35mm in existence. On Last Steps we had a couple of reels that were telecined [ed. i.e., digitizing film to video] and we weren’t happy with the results. I knew if we were going to make a feature film about Apollo 11 I wanted to start from scratch.

We had a couple of years to do it so time was on our side. It took some convincing on the part of the National Archives, which for the most part is the end repository for all of the film footage that NASA shot over the years. The crew that we had assembled, led by our archive producer, identified how much there was. We cast a very wide net, and about four months into that research project, these reels of large format (film) were brought to our attention through the supervisory archivists at National Archives. The reels themselves just said “Apollo 11” on them; some had dates, but we didn’t know the condition.

POV: That sounds promising, provided they’re in usable condition!

Miller: If you open up a reel of film you can tell just by the smell what kind of condition it’s in. [If you smell vinegar, the footage has deteriorated.] We didn’t know exactly what was on them and there was no real way to play them back.

POV: So you had to scan them to see what treasures you found, using new technology to bring the images to life.

Miller: I was working with a post-house at the time, Final Frame in New York. Will Cox has been my Digital Intermediate colourist for a long time and was just getting into the film scanning business when a lot of other companies were getting rid of theirs. He had been developing new technologies with some partners to tackle large format film and other flavours of film. This particular prototype scanner was able to have (to use) a wide swath of different gauges of film and not be reliant on the old “pin registration” methods. The film negative itself was riding on a cushion of air, so we didn’t care about perforations. That allowed us to scan a bunch of different varieties [of film stock], and it also expedited the process as well.

From the first frame of footage that we saw from those test scans, our jaws were on the ground.

POV: How had this footage been used contemporaneously?

Miller: Some of the shots were used for a feature film called Moonwalk One (1969), which has become a cult classic among space enthusiasts, myself being one of them. It was shot by these tremendous large format filmmakers, in particular the Francis Thompson Company. Thompson himself was slated to direct it, but one of his editors, Theo Kamecke, stepped in at the last minute. There were two cinematographers, Urs Furrer and Jans Boyen, a Dutch filmmaker, that got all of the great scenes.

When we first started, we thought that all of the found footage was from Moonwalk One. Not so! NASA had actually been shooting on large format all the way back to the Gemini program through their Technicolour facility. They had at least a couple of cameras with technicians that were shooting large formats through all of those missions. You can tell that they were still getting to know the systems for some of the early Apollo missions, but clearly, as evidenced by the film, by the time Apollo 11 rolled around, they knew what the hell they were doing.

POV: There’s a balance between footage NASA shot for “aesthetic” or documentary purposes and other shots that were meant for engineering purposes, such as the closeups of the launch. How did the handling of that material differ?

Miller: They were shooting some of the aesthetic stuff for actual industrial films and then just documenting history (with the rest). There’s one particular film called Bridge to Space – It’s a really good 30 minute film that was produced by NASA and ended up in the National Archives system that was produced for publicity purposes and cut down to 35mm for that purpose.

The engineering film which is predominantly 70mm 10 perforations, commonly referred to back then as “Military Grade 1 footage”, was shot by the engineers at Marshall White Centre and resides there still to this day. We got around 100 reels of that and scanned all it.

We owe a debt of gratitude again to Theo Kamecke, the director of Moonwalk One, who back in 1969, shortly after the launch, went to Marshall to get those scenes for his film. He asked the engineers, “What are these reels?” They said “Oh, you wouldn’t be interested in those. We only look at them in case the vehicle blows up or some catastrophe happens, and then we can reverse engineer it and hope it doesn’t happen again.” So Theo said “do you mind if I take these and go get them processed back at in New York?”, which he did, and so that was the first time that any of these ultra-high slow-mo sequences of engineering the launch had been shown.

Moonwalk One was the first one to do it, and it’s been replayed in countless nonfiction and even fiction films.

POV: One of the more beautiful shots is clearly meant originally for the engineers. It’s where the camera is left on and we drift from the capsule to the black of space, only to have the earth slide back into the shot before the film runs out.

Miller: The camera was put on the stage separation between the stages of the capsule. The [negative] itself is 16mm film: it rolls out, then pushes forward, ejects itself out of the Saturn 3rd stage, reenters the atmosphere through its own space ship and then has its own little parachute and lands in the ocean. NASA scooped it up and brought it back and processed it!

POV: So, we have 16mm, 35mm, 4 perf 65mm; we’ve got 10 perf 70mm. Any 8mm footage?

Miller: We do have 8mm, too, for some DVD extras we’re going to show. There’s some home movie stuff that we got, like Johnny Carson and Isaac Asimov riding in the private jet with Ed McMahon on the way to go to the launch. There’s 8mm via footage from the Nixon Library with the President preparing [a speech with] H.R. Haldeman in the ”oval room.” Predominantly we wanted to let the large format stuff shine.

POV: You mentioned this could have been a nine day movie. There must have been stuff you were gutted to lose.

Miller: I just love two hour films, and for this particular story, I felt that it deserved to be a feature film. IMAX was always in the back of our minds. We called our film “Dunkirk in space,” in the sense that the story had been told before. Before you had Darkest Hour, there had been countless documentary series about Dunkirk. What Christopher Nolan’s film did was to drop you into the story and ask you to take a ride, from which you were lucky to come home. That’s exactly what we set out to do with this.

POV: Damien Chazelle’s First Man is so insular while your film is very much about the event. Seen together, they pair remarkably well. Could you talk about your own relationship with the film and how you connected with it?

Miller: The X-15 sequence in the beginning is absolutely amazing! I ran into Damien at Sundance and we were joking around. I said “I’m glad you went first!” His landing sequence was exactly what I wanted to do, pushing through the window and having the dead silence, so we had to come up with something else, which was very challenging. A lot of the same people were working together on our project—the families, the astronauts. We both had Burt Aldrich, a wonderful film liaison coordinator at NASA, and his department assisting us. When First Man was coming out I personally was just freaking out because we were trying to survive government shutdowns and everything else!

It goes to show that with Damien did with his film was to show you new ways to look at something that you thought you knew. There are constantly evolving narratives showing that this magnificent event happened and how so many people came together (because of it). In our film you witness that on a grand scale, but you also realize the human element in Damien’s film. As Walter Cronkite describes it, “the burdens and the hopes fell on individuals and they did something that was just extraordinary.”

POV: Did the productions share film elements or scans?

Miller: No. We just missed each other actually. They had one reel out of Marshall. IMAX had put on their very slow scanner in London—-I say slow compared to ours! They were using it more for reference for recreation with the visual effects team. We had those exact same reels and then about ninety other ones that we got out of Marshall to scan.

POV: So you weren’t waiting for them to finish before you could start?

Miller: We were so backlogged at the time that we had to wait almost until First Man was in theatres [to continue our process]. It was certainly very late in the game for them to utilize the things that we were working with.

POV: I’ve been comparing your film to Woodstock (dir. Michael Wadleigh, 1970). Were there specific films that gave you a touchstone to be able to tackle this sort of work?

Miller: I’m trying to constantly educate myself on cinema. Woodstock owes everything to the earlier large format filmmakers. Theo Kamecke edited a film called To Be Alive for Francis Thompson. They shot that film, as they did a lot of their large format films, for Science Centers, Expos and museums. To Be Alive was actually shot in Cinerama, so it had three cameras and three projectors, and was shown at the 1964 World’s Fair in New York. To qualify for the Oscar, they had to do a single screening. What they did was take the Cinerama [shots] and split-screen, which was very cutting edge for its time. They incorporated that in subsequent films throughout the late ‘50s and into the early ‘60s. [Ed. To Be Alive won the Oscar for Best Documentary Short at the 38th Academy Awards]

When Scorsese the other greats were editing Woodstock, they were looking to these types of films because they had grown up on them.

Francis Thompson did another film called N.Y., N.Y. (1957), which is truly avant garde. Francis and Charles Morrow, who ended up scoring Moonwalk One, were experimenting with fractured narratives, things like whisper narration, 30 years before Malick was doing it!

Then there’s Godfrey Reggio, with Koyannisqatsi (1983) of course, but some of his later work, like Visitors (2013) is also terrific. I’m in love with that style of filmmaking! Ron Fricke was his D.P on the Koyannisqatsi series and went on to do Baraka and other really great stuff.

POV: Al Reinert’s 1989 film For All Mankind is a clear and obvious influence. You even dedicate your own work in part to him.

Miller: Al and I developed a friendship before he unfortunately passed away recently. I just was enamored with his film. Obviously we’re just another extension of the work that he and others made by combing through the archives. I’m excited to see what other people do!

POV: You’ve noted that the reaction to Reinert’s film was “polarizing” from members of the space community because of how he merges multiple missions together in one narrative.

Miller: To Al’s credit, that was his intention from the start. His reasoning was that this was a collectivist experience, through all of the Apollo guys, which I completely agree with him.

POV: How did you engage yourself and avoid similar conflicts?

Miller: One thing that we did was try to engage with the space community early and, in particular, with the astronauts who were there. It was one of the joys of my life to work with Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins, and Neil [Armstrong]‘s sons, Rick and Mark, to try to get it right.

For instance, there’s a scene in the landing where the 1202 and 1201 alarms are going off. I’ve never heard the tone of that. NASA’s history department got us some documentation through MIT that showed exactly what it was–an 8kHz tone that went on and off—so we got to play that for Buzz and ask if that what it sounded like. We’d go back and work on it and show it to him.

POV: So the point was to be accurate, but not slavish to the single mission. Like Reiniert, you draw from other missions, but do so to tell one journey’s story.

Miller: If you ask Neil Armstrong what his most idyllic moment was during Apollo 11, it wasn’t landing on the moon, putting the footprint down on another world for the first time, or even coming home safely. It was seeing the moon about 100,000 miles out while a solar corona was happening. Well, those guys didn’t shoot that, but somebody else did on another Apollo mission. It was great to show that to Buzz and Michael and ask “did it look like this?” “Well, we were a little bit further out.” OK, we’ll zoom out a little bit, put some more rays around it. “Oh, that’s perfect, that’s exactly what it looked like.” We have the audio of them talking about it on board, but to show a visual representation of it and to have basically the blessing and the accuracy validated by the guys who were there, gave us the justification.

We actually only did it in a couple of other places. For instance, the translunar injection burner, which is when they go around Earth’s orbit a couple of times, and then fire the rocket to go to the moon. That actually happened on the dark side of the Earth. They call it TLI and riding the sunrise and all of the Apollo astronauts talk about it because it happened on a lot of their missions. They didn’t shoot it on 11 but they did on Apollo 9, so we were able to show that to Michael and to Buzz and get their validation of it.

POV: You’re not hiding these elements drawn from other missions, and even talked of putting up a website detailing shot-by-shot the source of these images.

Miller: When you work with these materials, you don’t know its provenance. The research project was to figure out not only the technical side, but who were the filmmakers (on each mission). We had to do an immense amount of research that I hope no one ever has to do again.

It was such a joy to influence a historical record. You realize how underfunded NASA is when you work with them, and how undermanned they are, and how special are the people and their work. These images belong to all of us, so for future generations we need to make sure they understand and appreciate how tough it was not only to organize these materials but then to present them in a proper way.

POV: It’s very rare that a filmmaker can come into these circumstances and leave things better than how they started.

Miller: Usually we trash locations!

It’s refreshing to hear that (our experience with them has) made NASA more open to working with filmmakers. This was the first time in years that materials had actually left the building. I hope it paves the way for future filmmakers to interpret not only the same materials but other things. Who knows what’s lies next to the Ark of the Covenant with all of the large format reels there!

Apollo 11 is now playing in theatres.