As soon as Joseph Nièpce took the first photograph in 1827, the race was on to invent “moving pictures.” After all, photography and cinematography adhere to the same principals of composition, lighting, exposure and depth. However, a century after the Lumières and Skladanowskys bridged the celluloid gap remarkably few photographers have become filmmakers and vice versa. Cinema and photography, though genetically linked, remain galaxies apart in their philosophical approaches and artistic effects. Why? In order to determine the essence of the moving picture, one must uncover the nature of the still image.

“FILM IS TRUTH AT 24 FRAMES A SECOND.” —Jean-Luc Godard

Documentaries about photographers offer clues to both answers, but photo docs have become common only in the past 20 years, reflecting the belated rise of photography as a serious art form. Instead, one has to go back to 1921 when pioneering American photographer Paul Strand collaborated with painter/photographer Charles Sheeler on the groundbreaking short, Manhatta (also known as New York, The Magnificent). Here, Strand translates his experiments in formal abstraction and an interest in social reform from stills to motion pictures. Manhatta collects images from a day in the life of New York. Crowds march down Wall Street. An ironworker balances on a high beam. The lack of synchronized sound or narrative only makes the resemblance to Strand’s photographs stronger.

After Manhatta, Strand’s photography and films diverged. As explored in John Walker’s fine documentary, Strand: Under The Dark Cloth (1990), Strand considered it “vital for a photographic portrait to convey a person’s personality,” but his films of the ’30s and ’40s are purely political, even propagandistic. In 1933, Strand’s Communist sympathies led him to Mexico to shoot Redes (Fisherman’s Nets), a docudrama that depicts the economic exploitation of the Veracruz fishermen of Alvarado. His 1942 documentary, Native Land, celebrated unionizing and lambasted fascists such as the Ku Klux Klan.

Though a master of portrait photography, Strand failed to make the leap from stills to cinematography. Redes’ co-director, Fred Zinnemann (who later directed the McCarthy parable, High Noon) remarks in Under the Dark Cloth that, “When it came to motion pictures he thought in terms of static photography rather than of movement.” Strand moved the camera only when his subjects did, making his films look stilted. Strand’s career suggests that a different set of skills is required to shoot motion pictures.

A decade after Native Land, two New Yorkers would create films that firmly establish a connection between photography and cinema. In The Street is a 15-minute short released in 1952 by photographer Helen Levitt. She based her 16mm footage on her own acclaimed photos of children playing in New York’s Spanish Harlem. This “observational documentary” is a simple, yet heartfelt collection of real-life scenes that has moved Stan Brakhage to rank it with D.W. Griffith’s Intolerance and Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin as one of the greatest films ever made. Brakhage called it “a definite must in both photography and film classes, because it is one of the very few films ever made that possibly bridges both arts.” The reason may be that the film has no storyline, for its charm resides in its images. Similar to Manhatta, the artist behind In The Street made the successful leap from stills to cinema, but purely in visual terms. An element was missing.

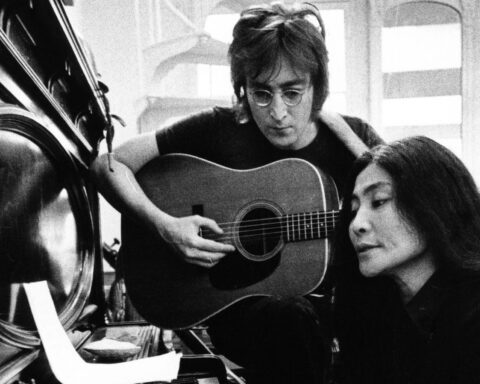

In complete contrast, Day of the Fight follows a hungry, young boxer on the day of his middleweight bout. Released as a newsreel a year before the Levitt film, Day of the Fight was directly modeled after a Look magazine photo-story of the same boxer, Walter Cartier, entitled The Prizefighter. A young photographer from the Bronx named Stanley Kubrick shot the photographs as well as the film.

The difference between Levitt and Kubrick was that the latter was a storyteller. Whereas Levitt could capture on still or 16mm film moments that enchanted audiences, Kubrick was able to sequence his moments into a complete storyline. He grew up on movies and started photographing as a teenager. These two passions would drive his filmmaking career. In particular, 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) and Barry Lyndon (1975), are celebrated for their brilliant master shots that only a photographer could compose.

Kubrick is a rare example of a photographer leaping into the fictional filmmaking scene. Most photographers who venture into motion pictures, like Robert Frank, shoot documentaries. In his landmark book, The Americans, the Swiss-born photographer captured ’50s America in an honest, unapologetic way that de-glamourized the sunny Eisenhower era and outraged many upon its release. Frank applied his detached photographic style to his docs, most notably in Cocksucker Blues (1972), the rarely seen chronicle of the bawdy Rolling Stones tour of 1972. That tour supported their album Exile On Main Street, which Frank also photographed. In a brilliant move, Frank captures most of the off- stage footage through a blue filter, which casts the circus life of these rock stars in a surreal light. By contrast, all the concert footage is shot in colour, ironically making the Stones more real to us when they are performing onstage than off when they are being themselves.

Juxtapositions like these propel Cocksucker Blues above the run-of-the- mill rock doc. In one dreamy collage, Bianca Jagger opens a music box. As it innocently chimes, the film cuts to overlapping images of a road trip somewhere in the American South: a billboard, a calendar, license plates in a souvenir shop, Bianca eating. Images float and collide at random, like recalled memories, then suddenly vanish in a rush of performance footage. This approach does not convey any hard, literal meaning as a typical documentary might, but does impart an impression of life on the road that is chaotic, languid and even alienated, the same qualities that are found in The Americans’ photographs. Disregarding its cachet as a forbidden film, Cocksucker Blues is a great movie that successfully blends linear footage (colour concert) with experimental (off- stage blue) and marries photographic elements (unrelated images) with the cinematic (montage).

“PHOTOGRAPHY HAS A KIND OF REALITY WHICH IS ALMOST ILLUSION.” —Nobuyoshi Araki

Since the early ’70s, photo-related docs have shied away from such a radical approach and fallen into two broad camps: bio-docs and photomontages. Of the former, standouts include the aforementioned Strand: Under the Dark Cloth, the recently acclaimed What Remains about Sally Mann, Shooting Indians: A Journey with Jeffrey Thomas (1997) by Ali Kazimi, The True Meaning of Pictures (2002) by Jennifer Baichwal, Girl In A Mirror (2005) about Australian rebel Carol Jerrems, and Travis Klose’s Arakimentari (2004) profiling Japan’s infamous Nobuyoshi Araki.

Each film succeeds by transcending the standard bio-doc formula and presenting a unique theme, based on the personality and artistry of the respective photographer. Paul Strand was a political activist. Sally Mann explores mortality and the flesh through her photographs of human corpses. Kazimi takes a novel approach by delving into the ethnic identity of himself and fellow “Indian” Jeffrey Thomas who rails against the First Nations photographs of white American, Edward S. Curtis. Ostensibly a profile of an acclaimed photographer, Shooting Indians is really a journey about accepting one’s racial identity in a hostile society.

The True Meaning of Pictures delves into the touchy issue of photographer Shelby Lee Adams exploiting his subjects, the poor whites of Appalachia. Is the photographer presenting these “hicks” in a dignified light, or is he using them to advance his career? Just where is the line between representation and rip-off?

Mikael Wiström’s Compadre (2004) asks the same questions, but here Wiström is both photographer and documentarian. He met Daniel Barrientos while photographing an Ecuadorian garbage dump in the early ’70s. Wiström the Swede befriended the impoverished Ecuardorian, and has since made two films about Barrientos raising a family against all odds (the first was 1992’s The Other Shore). In one tense scene in Compadre, Barrientos asks Wiström for a loan so he can replace the engine in his mini-taxi, knowing that he’s serving as the subject of both of Wiström’s films without seeing a dime.

In Girl In A Mirror, Kathy Drayton takes us on a voyage in Australia in the ’60s and ’70s through the lens of Carol Jerrems. The rebel photographer documented the social revolution, which forced Australia to evolve from an uptight British colony into a modern multicultural society. Jerrems sought out Australia’s outcasts—Aboriginals, punks, artists–in a provocative manner that defied sexual and racial taboos.

Similarly, Nobuyoshi Araki has flaunted Japan’s norms by photographing scandalous pictures of nude, and sometimes bound, women. Araki’s ebullient personality shines in every frame of Klose’s film. This incisive doc reveals Araki in some candid, thoughtful moments in which the world’s most prolific photographer offers insights into the nature of photography. Whereas Jean- Luc Godard believes that “film is truth at 24 frames a second,” Araki says that “photography has a kind of reality which is almost illusion.” He explains: “Photography is about a single point of moment. Everything gets condensed into that forced instant.” Action is frozen, expressions are fixed, details expand.

Photomontages exploit this virtue but also employ cinematic montage to create a hybrid form. Canadians excel here. Le Québec vu par Cartier-Bresson, directed by Claude Jutra in 1969, is an early success that sequences still images of Québec-in-transition as shot by French legend, Henri Cartier-Bresson. The sound effects approximate the pictures on screen, but no narration or context is offered, leaving the audience to interpret the images.

An early Ron Mann short, Marcia Resnicks’ Bad Boys (1985), is a witty slideshow of Resnick portraits of Studio 54 playboys such as John Belushi and Mick Jagger accompanied by her wry commentary. More recent is El Ring (2002) by Carl Valiquet and Richard Gravel, which gathers Valiquet’s superb sepia pictures of child boxers in Cuba. Zooming, panning and quick cutting over the sounds of a boxing ring convey a boxer’s frenetic movement without resorting to any motion picture footage. Using the same approach but to dreamier effect is Parfum de lumière (2003) (Fragrant Light) in which Serge Clement dissolves together his images of old rain- swept Shanghai and Hong Kong.

Perhaps the best film in this category is Stefan Nadelman’s award-winning Terminal Bar (2003), which pays tribute to the denizens of a formerly seedy Manhattan bar. Imaginatively edited, using pans, zooms, dissolves, multiple images and a funky soundtrack, Terminal Bar gathers reminisces of the bartender- photographer who relates the stories behind the sad, expressive portraits he took of winos and gay junkies.

Though striking and occasionally stunning, the photomontage is limited to the short form. A sequence of still images would not sustain a full-length feature, and begs motion pictures. Another crucial (and obvious) distinction between stills and motion images is sound. Stills rely on the viewer to ascribe a voice to the subject and to imagine the overall context. What happened before and after this picture was taken? What is the subject thinking, feeling and saying? A silent still image, where a single moment is magnified, elicits a reaction from the viewer altogether different from motion pictures. A great photograph resonates, burned in the memory like chemicals on celluloid, and evokes its own world. “A thousand words,” goes the proverb.

In contrast, motion pictures rely on sound to make sense, and depend on montage to establish a context. A single photograph can tell an entire story, but a scene taken out of a motion picture is confusing. Furthermore, a photograph often has more impact than motion picture footage of the same event, as if the realism of the moving image demystifies the event.

Two examples come from the Vietnam War. Though American and international TV covered the war every day for several years (even in living colour), the most potent imagery from Vietnam were the still photographs. Eddie Adams’ 1968 black-and-white picture of Nguyen Ngoc Loan, South Vietnam’s national police chief, shooting a suspected Vietcong agent in the head turned public opinion against the war. In this prize-winning photograph, the prisoner faces us with his arms behind his back, his face contorted as the gun has just fired. Loan’s back is to the camera, his face in weak profile and his right arm dominating the frame as he has just squeezed the trigger against the prisoner’s temple.

In motion picture footage the scene is just as horrific, but the effect is totally different. The actual shooting happens so quickly that Loan is forgotten. Instead, the film camera lingers on the prisoner spewing blood on the street like a slaughtered animal. In contrast, the photograph captures a relationship between executor and prisoner, the powerful and the helpless, that outraged many in the late ’60s.

Four years later another image would change the course of Vietnam, as documented in Kim’s Story: The Road From Vietnam (1996). Shelley Saywell’s film best demonstrates the difference between the still image and motion picture and remains one of the greatest films in the photo doc genre. Kim’s Story traces the life of Kim Phuc ever since she appeared as a nine-year-old girl running naked from her Vietnamese village as her body and home was burned by napalm.

The Associated Press’s Nick Ut took the photo on June 8, 1972 during an errant napalm strike by the U.S. Air Force. Shot with a 300mm lens on a Nikon, Ut’s photograph won a Pulitzer Prize and immediately symbolized the war. This single black-and-white image shocked the world and continues to haunt those who see it.

Ut’s photograph forces the viewer to see things we’d miss in a motion picture. The boy on the extreme left is terrified and crying. You can almost hear him screaming through his gaping mouth. A small child in the background looks back at the inferno that has eviscerated his village. To the right, an older girl grasps the hand of a little boy as they run. Several armed soldiers and journalists in battle fatigues trail the children. Behind them all is a sky full of hellish black smoke. And there, directly in the centre of the image is the little girl Phuc, naked and flailing her arms. She screams in terror like the Edvard Munch painting.

Compare that to the colour motion picture footage. The scene remains horrific, but the impact is slightly dulled. Phuc cries until U.S. soldiers pour water from their canteens to cool her burning skin and hydrate her. The girl looks confused, scared, relieved, pained. There is not one single image that dominates the viewer, but several.

A motion picture is a sequence, no matter the length. A character goes from A to B and the viewer is left to surmise what that sequence means. In a photograph, there is no A to B. There is only a sliver of time forever captured. A second earlier or later would have yielded a different image, no matter how slight, and elicited a different reaction from the viewer. In Phuc’s case, a second earlier she was emerging from a cloud of smoke with her fellow villagers. A second later saw her drinking water out of a soldier’s canteen. The audience inevitably asks, What happens next and what happened before? When looking at the Ut photograph we ask,“What is happening?”

Again, the existence of sound in a motion picture brings us closer to the reality of the moment, but also demystifies it. The Nick Ut photograph of Kim Phuc resonates because we do not hear her scream. Instead, every time we look at that image we imagine hearing a child scream. Once in a while the gulf between photography and cinema is bridged. In 1999, the BBC asked Magnum photographer, Martin Parr, to put down his still camera and pick up a videocam. The result was the wonderful Think of England. Renowned for his over-saturated blow-ups of baked beans, overweight sunbathers and Ascot, Parr went around England asking his countrymen one question, “What is Englishness?”

Remarkably, the dry wit and pop culture that run through Parr’s pictures successfully translate to the big screen. Both his photographs and films search for, yet also tease the English identity: bad weather, eccentricity, stoicism, xenophobia. Think of England largely succeeds because Parr’s playful yet intelligent personality shines through. His witty give-and-take with his interview subjects, from a stodgy couple who are proud never to vacation outside England to British-Pakistani kids playing street “football” animate his acclaimed photographs. Nearly 200 years after Joseph Nièpce, Parr is one photographer who has literally made “moving pictures.”