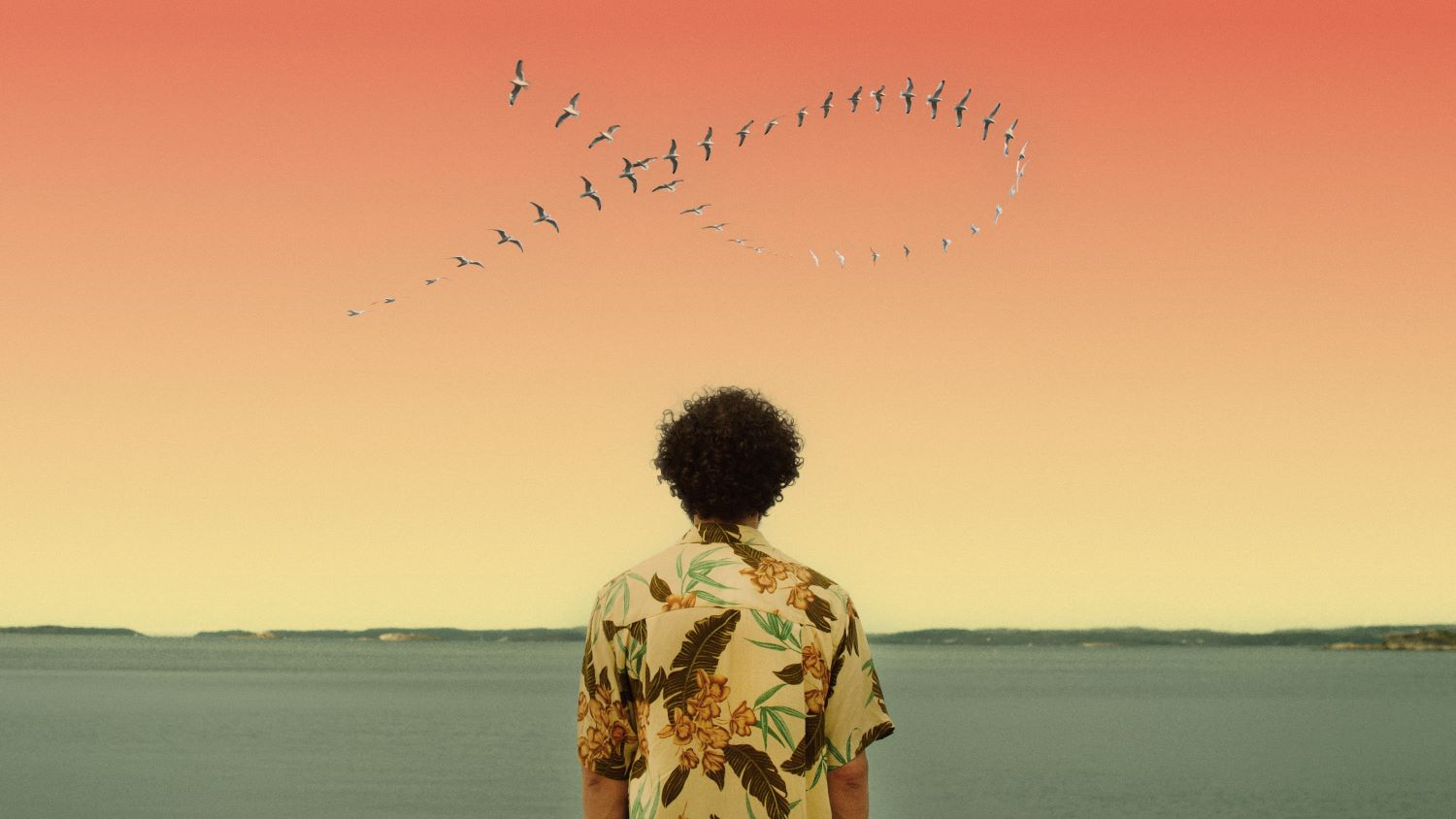

“I heard seagulls outside my window and thought they were flying surveillance robots,” says musician José Gonazález in A Tiger in Paradise. “The flashing light from the smoke alarm signalled to me what I should do, when to lie still or get up. It became my reality.”

The artist shares his experiences with mental health and wellness in A Tiger in Paradise. Directed by Mikel Cee Karlsson, the film harnesses González’s quest to feel grounded. It opens with invigorating archival footage of González performing a concert to a packed crowd that claps and stomps its feet. The energy of the moment yields sharply as Karlsson cuts abruptly to am image of González’s smoke alarm. The singer then lies paralysed beneath it, sharing moments of introspection that inform and glimpses into his creative process throughout A Tiger in Paradise. The film hovers above the artist’s reality as interludes observe him in moments of inspiration—playing his guitar, singing, and writing lyrics that double as existential voiceover. But Karlsson shrewdly taps into his collaborator’s brainwave by exploring the deeper philosophical questions that González’s music invites. He presents González’s story like a cinematic album. Yes, songs play throughout A Tiger in Paradise and some segments could easily be extracted as elevated music videos as Karlsson presents imaginatively realized vignettes that convey the intellectual and emotional tonalities of González’s songs.

But what emerges is a conceptual approach to music documentary, much like the way in some musicians conceptualize an album as a unique work to experienced as a whole, rather than a series of connected singles. Like an album, A Tiger in Paradise builds one scene upon the other as Karlsson, who recently served as film editor of Palme d’Or winner Triangle of Sadness, rhythmically situates González’s music into a pattern of waking days, wellness routines, musical riffs, family life, and surreal moments of black comedy sparked with existential dread. Everything bridges to a violent yet idyllic encounter with the titular tiger: there are no easy answers here, but rather an exploration of life’s deeper questions, scored to mellow vibes that invite a viewer to open themselves to a truly zen cinematic experience.

POV spoke with Karlsson briefly via Zoom ahead of the MUBI release of A Tiger in Paradise to discuss his collaboration with González, his inspiration for the film’s dreamy interludes, and the doc’s unique roadshow release.

POV: Pat Mullen

MCK: Mikel Cee Karlsson

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

POV: You worked with José before on The Extraordinary Ordinary Life of José González. What inspired you to look at his work again in a new feature?

MCK: Me and José have been working together since 2007. We made two music videos back then, “Down the Line” and “Killing for Love,” and then we started the first feature documentary, but that was more of a film about the creative process. Then we just kept working together. We became close friends and we’re interested in the same subjects and read the same books. We’re both really into philosophy, neuroscience, sociology, and so forth. We can discuss pretty much any topic. We’ve had a lot of discussions about free will lately.

This film is a pandemic project, in a way. The idea came up during the pandemic because we were in this bubble and we were working together. The idea came up to do something based on the first scene in the film [of the concert and the smoke alarm]. There’s the topic of his mental health issues and José’s psychotic episodes. We use that as a jumping off point to discuss the importance of other ideas, beliefs, and perceptions.

POV: Did you know about José’s experiences with mental health before this conversation came up? How do you navigate exploring that aspect as a friend on one hand, but then as a filmmaker on another?

MCK: I knew about them and I knew that he’d had one episode before I met him. He has had a couple of episodes, but they’ve been far apart. He actually hasn’t had one since he’s been doing the regimen that we show in the film. He’s really taking care of his sleep and stress levels and everything like that. It seems to be working very well. We didn’t want to do a film that was too much into that [mental health] as a subject. It’s a big thing in Sweden right now. I wouldn’t say it’s an epidemic, but you can see in it society in a big way. Me and José wanted to do something more existential. But it was important to have it as a starting point because there’s a twist in the beginning about how we perceive reality.

POV: The creative process is such a part of that, and people can work through what they’re experiencing by creating things like music and film. How did the hybrid approach to the film come in? There’s some wonderful, surreal shots, even just the one dramatic vignette of a man sitting in the field with his sandwich and a beer and then falling off the cliff. Were those coming from dreams?

MCK: No, they’re coming from me. Sorry! [Laughs.] I think the one that you’re referring to is almost like a short film in itself. It’s in the section of the film that talks about rationality, so it’s a play on that. But I think a better example is the scene with the tiger in paradise. That whole sequence is based on depictions of paradise from Jehovah’s Witnesses. They have these depictions of what paradise would look like when everything is fine: There’s good weather, everyone’s friends, and you can live with friendly tigers. The idea is basically what happens if you take that fantasy or that idea and place it in reality. In this case, someone loses a leg, so there’s a lot of play on fact versus fiction.

The crawling animations are based on something called Game of Life, which is a simple mathematical algorithm that’s based on four simple rules. These squares, they’re either black or white, alive or dead, and depending on their relationship to each other, they start interacting. It’s an evolution, in a way. Depending on their interaction, they can start to spread and evolve and create almost living organisms. We used it in a symbolic way in the film—how ideas clump together and [we] send them out into the world.

POV: How involved was José in the conceptual approach to what we’re seeing in the film? When he’s playing his guitar, does he know that graphics will flow over him?

MCK: Actually, those are projected into the room. We discussed everything because it needed to be ideas that are attached to him and that we’re both interested in, so there was definitely a collaboration. The one with the tiger was the only one that he didn’t know beforehand. He liked it once he knew about it, but it was my reference.

POV: You perform various roles in your film: You shoot it, you edit it, and you direct. How does juggling different stages of production inform the creative choices you make in each one?

MCK: It’s actually a pretty special project because it was so planned out. Since we were in a little bubble during the pandemic, we’re a small team. We planned scenes and shot them around José’s summer house, and then edited the scenes. We knew that we had what we were looking for, so it was a quick edit. I think 99% of what we shot is actually in the film. That’s special. It’s not how we usually do it. We planned out every little detail, even the things with the smoothies [that José drinks daily]. Every little thing is planned because they’re based on [José]. There might be more documentary filming with his daughter, for example, waiting for certain scenes.

POV: The event series that you and José are doing is such an interesting concept. Can you talk more about that, and with the film coming out on MUBI, how can audiences at home recreate that experience?

MCK: People adopt these ideas, then they distribute them, and they keep on going. We’ve been doing a special event that starts with the film, then me and José have this special type of talk where we go into these subjects in depth and talk about the backgrounds and connect it to music and he plays live.

We’ve been talking about filming one of the shows because we have a couple of shows left. But I think that the film can stand for itself. But when you go in depth into some of the ideas behind it, then it becomes a bit more, I wouldn’t say controversial, but we’ve had standing ovations and walkouts on every show, which is interesting. I think it’s more standing ovations [laughs], but people react when you talk about beliefs that are close to their hearts. We want to have a discussion. It’s not that we’re trying to be provocative, but it can be.

A Tiger in Paradise begins streaming on MUBI December 8.