When I first saw 2001: A Space Odyssey, I thought it could have been a documentary.

It certainly went right over the head of eleven-year-old me, watching it weeks after its premiere in 1968 in wide-screen Cinerama at the Glendale Theatre in Toronto at my friend’s birthday party excursion.

It had for me the quality of what Christopher Frayling later wrote in his book The 2001 File: Harry Lange and the Design of the Landmark Science Fiction Film, that 2001 was “a kind of semi-documentary about things that had not happened yet.”

2001 redefined expectations of what big-screen storytelling could do, partly by putting less emphasis on story, action and exposition and more on experience and the contemplation of things bigger than plot: our place in the universe, our relationship with technology, and what it means to be intelligent, conscious and human.

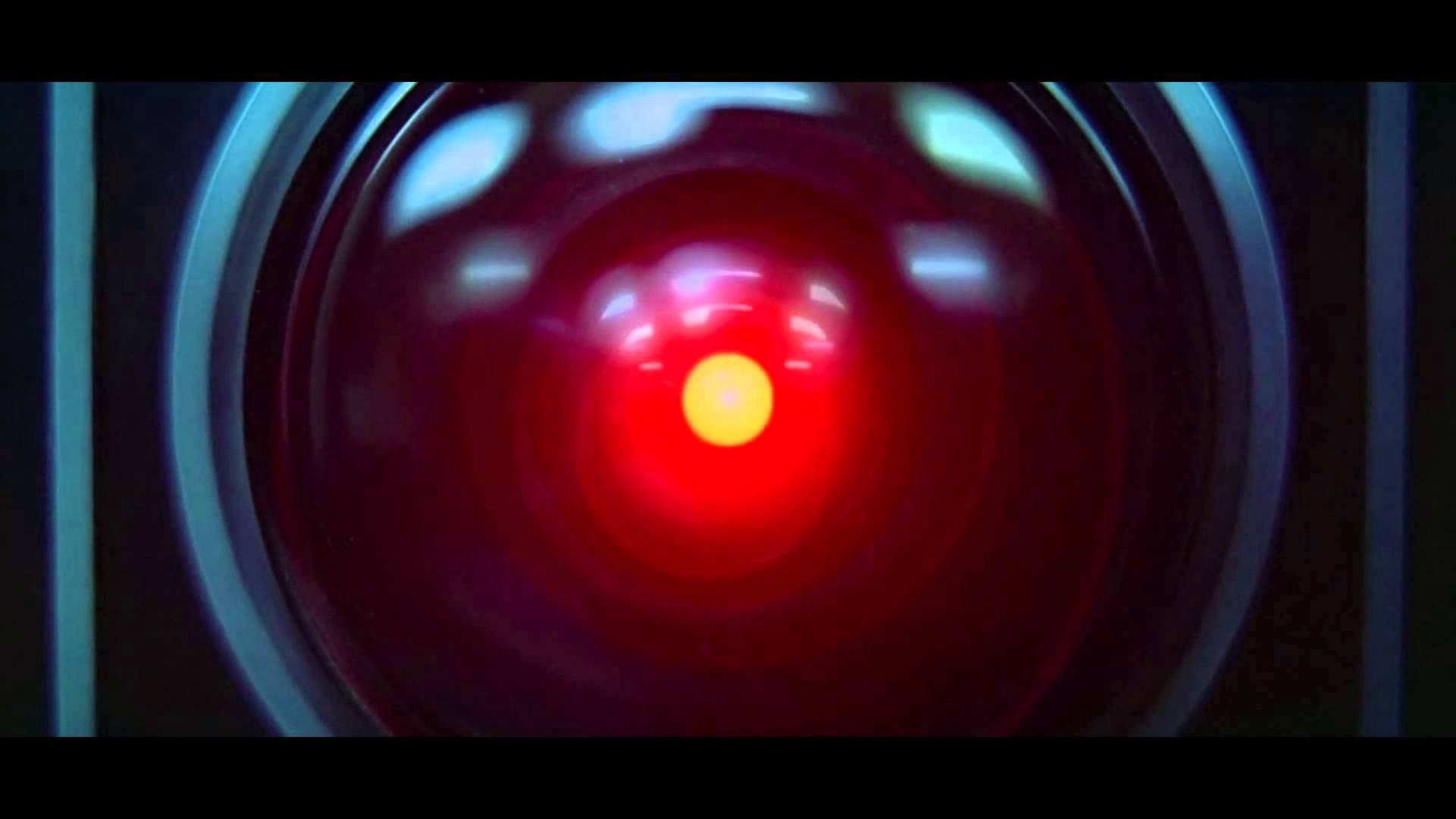

A Canadian documentary had a huge influence on Stanley Kubrick and the making of 2001. The voice of its most recognized and evocative character, the omniscient but homicidal HAL 9000 computer, was spoken by the narrator of that documentary, Universe, and appeared in another, The Stratford Adventure, uncredited, opposite Obi-Wan Kenobi. (Well, Alec Guinness, that is).

Winnipeg-born actor Douglas Rain, who turns 90 May 10, is the inconveniently all-too-human HAL. Rain, a star of the Stratford Shakespearean Festival for almost 50 years, completed his voice-over recording for Kubrick in a day and a half.

This is the story of a voice, its documentary roots, its skilful theatricality, and its impact on the culture and technology.

Despite the sparseness of his dialogue (only nine brief conversations in the entire film) HAL is perhaps the most memorable non-animal character in the history of cinema.

That unmistakeable voice–measured, persuasive, authoritative and strangely serene–has had an influence on how we think artificial intelligence should sound. Inadvertently, that means AI (artificial intelligence) sounds just a bit Canadian.

Echoes of HAL can be heard in Amazon’s Alexa, Google Home or Microsoft’s Cortana, and even in the TV commercial persona of IBM’s Watson. As we engage in ‘conversations’ with digital assistants, and warily eye a world forecast to be utterly transformed by AI incursions into all aspects of our lives, HAL is lurking. (But not for long, perhaps – the new Google Duplex AI system sounds enough like a real person to make phone calls on your behalf, including conversational um’s and ah’s.)

Scott Brave, co-author of Wired For Speech: How Voice Activates And Advances The Human-Computer Relationship, says HAL’s voice “influenced the perception of what the norm is for what is appropriate for a computer voice to sound like. That’s been reinforced over time–other filmmakers have presented their automated/machine/robotic voices in their films, but there is an anchoring effect [with 2001], i.e. the first momentous time that you perceive something tends to anchor your perceptions. I think there is a very strong likelihood that voice has a ripple influence–and when I listen to something like Siri I feel there is a lot in common.”

Terry O’Reilly, host of the podcast and CBC Radio program ‘Under The Influence’, feels HAL is “the reason why almost all phone prompts, guidance systems and GPS voices are female. HAL was controlling, unbalanced and menacing. He was so ominous that it made technology scary.”

Kubrick might not have thought it was scary, but inevitable. In an interview in 1969 he said of HAL’s role in the film: “One of the things we were trying to convey…is the reality of a world populated – as ours soon will be–by machine entities that have as much, or more, intelligence as human beings. We wanted to stimulate people to think what it would be like to share a planet with such creatures.”

50 years later, none of the acclaim and cultural resonance of 2001 and his part in it is of any interest to Rain (who retired from acting in the late 1990s). For him, the recording with Kubrick was just a job. And it turns out that Rain has never seen 2001: A Space Odyssey.

“FORGIVE ME FOR BEING SO INQUISITIVE”

Weirdly, HAL is a kind of ‘everyman’, attracting so many adjectives over the years that together they describe a character that represents the disturbingly rich variety of personalities AI might come to offer us.

Film critic Clyde Gilmour described his voice as “silky, and baleful.” Director Sydney Pollack spoke of HAL’s “droll, evil sense of humour.” Writer Wendy Michener thought of him as “inhumanly cool.” One critic wrote of HAL: “right from the beginning, you know he is a fink.”

Anthony Hopkins has said that his inspiration for Hannibal Lecter’s speech patterns in The Silence Of The Lambs came from the idea of crossing Katharine Hepburn with HAL 9000.

Faceless in the film, HAL has been interpreted in many ways. Academic readings of HAL include ‘Straight, Gay, or Binary?: HAL Comes Out of the Cybernetic Closet’ and ‘What was HAL?: IBM, Jewishness and Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey’ (“It will be argued here that HAL can be read as an emotional, yet submerged, representation of the Jewish American Mother”).

Beyond the impact of Rain’s performance itself, the perception of HAL as more human than the humans also came about somewhat by contrast. Kubrick built up the verbal versatility of the computer and stripped away the emotional qualities of the astronauts’ language. The late Frederick Ordway, scientific consultant on the film, recalled Kubrick’s intense desire for the most likely possible scientific and technological verisimilitude, or as close as one could get, given that the film was projecting, from the 1960s, a future more than 30 years away.

Ordway described the evolution of Kubrick’s approach to language in the early days of 2001’s pre-production phase, telling Christopher Frayling that “we soon discovered that Kubrick had read voraciously —science fiction and space science—-and had developed a way of talking about them. He became fascinated with computers which had voice input-outputs. He’d talk about “neural nets”, “heuristic systems”, “logic elements”–he had quite a lingo!”

Frayling writes: “this ‘lingo’ was to morph into the jargon used by all the characters, the only means of expression they seemed to possess. The dialogue was to become deliberately flat, with the implication that the emotions lying behind it were becoming deadened by prolonged exposure to new technologies–and especially display technologies, all surface with no cables or plugs or evidence of manual skill to be seen.”

2001 historian David Larson told me that “Kubrick came up with the final HAL voice very late in the process. It was determined during 2001 planning that in the future, from a 1965 point of view that is, the large majority of computer command and communication inputs would be via voice, rather than via typewriter.“

Ordway explained that “HAL’s voice was a bit of fantasy, not developed logically like, for example, the potential shapes of spaceships” depicted in the film.

(In the film’s early development, the computer was female, named Athena, and it’s tantalizing to consider how it might have played out that way. At one point, Kubrick had female voices in mind for other uses in the film, noting to himself: “possible use of recorded voices for later on in the picture for suitable purposes: Joan Baez, Barbara [sic] Streisand, Marianne Faithfull”).

At first, Kubrick made what might have seemed like a traditional choice for the voice of HAL, Martin Balsam, best known as the ill-fated cop in Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho, and the amenable jury foreman in Sidney Lumet’s Twelve Angry Men. In 1966, Balsam told an interviewer: “I’m not actually seen in the picture at any time, but I sure create a lot of excitement projecting my voice through that machine. And I’m getting an Academy Award winner price for doing it too.” Kubrick wrote to a colleague at the time that “Marty Balsam was wonderful.”

Ultimately Kubrick said he “had some difficulty deciding exactly what HAL should sound like, and Marty just sounded a little bit too colloquially American,” but he felt that Rain “had the kind of bland mid-Atlantic accent we felt was right for the part.” He was right for the part, but his accent is Standard Canadian English.

Universe, Roman Kroitor & Colin Low, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

“I AM PUTTING MYSELF TO THE FULLEST POSSIBLE USE”

University of Toronto Professor of Linguistics Jack Chambers, in considering what Kubrick was aiming for, says “you have to have a computer that sounds like he’s from nowhere, or, rather, from no specific place.” HAL’s Canadianness stems not from “the specific stuff. It’s not the Canadian Raising (‘out’ pronounced as ‘oot’ and ‘about’ pronounced as ‘aboot’)”.

“Standard Canadian English sounds ‘normal –the vowels are in the right place, the consonants are in the right place, it covers a large piece of ground. That’s why Canadians are well received in the United States as newscasters, as anchormen and reporters, because the vowels don’t give away the region they come from. It’s entirely wrong to describe Rain’s voice as ‘mid-Atlantic’–the Canadian accent has almost no trace of Britishness.”

But there are traces in Rain’s voice of a largely vanished accent Chambers has named ‘Canadian Dainty’, one that evokes British-educated ‘upper class’ formality and precision.

“The only noticeably Canadian Dainty in Universe and 2001 is the ‘T’ voicing—- we say ‘water’ as if it has a ‘d’ or ‘putting’ as if it had a ‘d’ instead of ‘t’. Rain says ‘outer’ space (rather than ‘ouder’), and, as HAL, he says “l am putting myself to the fullest possible use.”

Chambers notes that “a few people are meticulous speakers and do this all the time—they do not have T-Voicing in their repertoire. The absence of T-Voicing is one of the marks of Canadian Dainty, as spoken by Robertson Davies and Vincent Massey and a lot of deceased English professors.”

Another Winnipeg-born actor, Kerry Shale, a long-time resident of the UK, recorded the voiceover for several of Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket theatrical trailers, and remembers the paranoia that some in the UK film industry had about the Canadian accent, “that you’re going to ruin their film by going ‘oot’ and ‘aboot’, so back then I would just lie about being Canadian—-I would say I was from Minneapolis.”

Shale is developing a film, Stanley Kubrick’s Voice, with filmmaker and screenwriter Jeremiah Quinn. They’re re-imagining Shale’s rather exhausting work with the director (“I wasn’t playing HAL, but we did do, like, 100 takes”).

In the script, the fictionalized Kubrick remarks to Shale: “There’s something about Canada. You guys can sound American but there’s something that’s in you that you can’t remove. It’s cellular,” but advises the actor: “Don’t let it hold you back.”

Of Rain’s HAL voice Shale says, “it’s very well rounded and very well modulated, and totally unspecific, which is the brilliance of it.”

Actor Brent Carver, also a Stratford veteran, describes Rain’s HAL as having “a Canadian voice, in the sense that it connects with people. It’s ‘mid’–not ‘mid-Atlantic’ as such. You can’t pinpoint where he’s from. Part of this planet, and not. He was training all his life for this moment. HAL is a completely conscious being, not just a voice, but a full person.” That Rain has almost never talked about his work as HAL doesn’t surprise Carver, who notes that the actor “always did the work and never discussed it after.”

Acting came early for Rain–he was in CBC Radio dramas by 1936, at age 8. But his friend, acting colleague and ex-wife Martha Henry, herself an acclaimed Stratford performer and director, recalls that Rain told her of the enduring power his performative voice had on him.

“When he was a child, the hope from his Scots-born parents was to give their son a skill in some art. So they enrolled him in voice and elocution classes. He was good at it, and quickly became sought-after for ‘presentations’ at functions such as the Kiwanis Club. He would memorize long narrative poems and then be dressed up to go out and recite. Douglas wouldn’t be allowed to play after school when he had one of these gigs but had to come straight home and have a nap. Many years later, he told me that he had a recurring nightmare as a child that he was in front of one of these gatherings, would open his mouth and nothing would come out.”

Studies at the Banff School of Fine Arts led to a scholarship at the prestigious Bristol Old Vic Theatre School in England, and, over the years, he performed on London stages alongside such stars as Peter Finch and Claire Bloom. A New York production of Robert Bolt’s play Vivat! Vivat! Regina led to a Tony nomination in 1972 for Rain. But his home was the Stratford stage.

Stratford stage manager Nora Polley paints a picture of an actor utterly at ease in the theatre: “in one production of Hamlet, he played Polonius, who dies early in the play but appears in the curtain call. Douglas used to get into his civvies, go home to watch basketball and then come back well in time to get dressed and appear in the bows. I wouldn’t have trusted any other actor to do that.”

Life in a repertory theatre company like the Stratford Festival means actors have to be versatile, and not just within the Shakespeare canon. Rain played a rich range of characters in more than 75 productions at Stratford, starting in its opening season in 1953, when he was Guinness’ understudy in Richard III. Over the years he was Macbeth, Sir Toby Belch, Iago, King Henry V and even Humpty Dumpty in Alice Through The Looking Glass.

In the 1957 production of Oedipus Rex, directed by Tyrone Guthrie, Rain is mellifluous and threatening. In the 1980 production of The Gin Game he is charming, informal and appealing. In his final season, in 1998’s A Man For All Seasons, Rain as Sir Thomas More exudes high intelligence, slyly weighing his words.

Henry says “he was a real ‘actors’ actor.’. You’d find the younger ones (and lots of the older ones, too) gathering to watch him in performance, in the wings of the theatre. His performances onstage were magnificent but in fact he always shied away from them slightly. He loved the rehearsal process. He wasn’t that interested in performing.”

You can see him rehearsing (with Alec Guinness looking on) in The Stratford Adventure, as a tormented, writhing Richard III. Rain as the king is so physically wrought with the nightmare of his dead victims coming to accuse and condemn him (“despair and die”) that he twists out of shape. It’s a remarkable ownership of the stage.

The Stratford Adventure, Morten Parker, provided by the National Film Board of Canada

“The ‘key’ to Douglas’s work, it seems to me”, says Henry, “is in his CBC Radio performances. That was where he always felt most comfortable and most alive. A listen to some of Rain’s performances in the CBC Radio archives reveals the versatility and authority of his voice. In a 1966 Hamlet, he plays Horatio, Hamlet’s friend, as a confident and powerful storyteller, the delivery of his lines almost musical. In his 1957 radio readings of some of Leonard Cohen’s poetry he has respect for every word. You can feel his whole body is in it, with a fierce assertion of the poetic truth.

Even in his early CBC Television work, it is his voice that is centre stage. Director Paul Almond cast him twice in biblical productions in a key off-camera role. “For Christ himself, well, only one–Douglas Rain–could play that.”

He ‘interviews’ Prime Minister John Diefenbaker in the 1976 documentary One Canadian, but it’s obvious his questions were dropped into the interview afterwards, built out of Dief’s answers, not the other way around, producing a weird disconnect, not unlike HAL, i.e. voice recorded at different time, after the live-action material was shot.

“I DON’T THINK I’VE EVER SEEN ANYTHING QUITE LIKE THIS BEFORE”

It was an unearthly voice-over job in Universe that first drew Rain to Kubrick’s attention. In the mid-1950s, filmmakers Colin Low and Roman Kroitor set out, at the National Film Board of Canada (NFB) to (according to film historian D.B. Jones) “not so much to convey facts about the universe as to invoke a sense of wonder about it.”

The documentary team’s task turned out to be as ambitious as the theme, taking almost seven years to complete, and inspiring the filmmakers to invent new special effects to depict stars exploding and galaxies in flux in a way that felt as realistic as the science of the time demanded.

Universe left its mark on Kubrick. One of 2001’s special photographic effects supervisors, Con Pederson, told Piers Bizony, author of ‘The Making of Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey’, that he remembered Kubrick screening it “repeatedly until the sprockets wore out, while he tried to figure out how they’d done it.”

Kubrick saw Universe 95 times, according to Rain. “I have found a narrator…I think he’s perfect,” Kubrick wrote to a colleague. “He’s got…the intelligent friend next door quality, with a great deal of sincerity and yet, I think, an arresting quality. The voice is neither patronising, nor is it intimidating, nor is it pompous, overly dramatic, or actorish. Despite this, it is interesting.”

One fan of the film remembers seeing it on local TV station WPIX in New York November 1963 as the first program broadcast immediately following President Kennedy’s funeral. Perhaps Kubrick first saw it then? But the U.S. version was narrated by Burgess Meredith, leading one to wonder what HAL would have sounded like voiced by the man who went on to be best-known perhaps for playing The Penguin on TV’s 1960s Batman series and the irascible trainer in Sylvester Stallone’s Rocky movies.

In The Lost Worlds Of 2001, “Arthur C. Clarke wrote that there was a possible sequence planned for the film, to be entitled ‘Universe’ to describe “the scale of the cosmos.” Universe was even considered as a possible title for 2001.

If one considers all of the various explanatory elements that were considered and then discarded for 2001 — a narrated prologue, interviews with philosophers and scientists, and considerably more exposition through dialogue — the film would have had even more of the feel of a documentary, and lost much of its incisive mystery.

Universe’s extraordinarily realistic depiction of the tumultuous life and death of stars led him to invite its co-director, Low, to New York to begin to understand how the NFB had done it. Low told Take One magazine’s Marc Glassman and Wyndham Wise in 2000 that Kubrick had briefly broached the idea with him of making 2001 on the NFB’s soundstages in Montreal.

“I don’t want to make this film in Hollywood [Low said Kubrick told him]. I may have to make it in England, but I really don’t want to. How about making it at the National Film Board?” Low said, “We’ve never done anything on that scale. We’ve got a beautiful shooting stage, but it is never used enough. Yes, we could.”

NFB managers didn’t jump at the chance of hosting the production of a gigantic Hollywood feature, but Kubrick ended up hiring one of Universe’s effects geniuses, Wally Gentleman (who left 2001 early – and hated the finished film).

Its narration written in a style that blended fact and poetry, Universe opens with an astronomer showing up for the night shift at the David Dunlap Observatory north of Toronto, and journeys to the unknowable edge of the universe, lifting Universe well beyond the usual grade school solar system lesson. An early draft of the film’s outline sketched its ambition: “the journey into the universe is really a journey into man’s soul.”

Universe’s producer, Tom Daly, told D.B. Jones that “Douglas Rain was so good professionally that, when he had done the whole text once through to his satisfaction, he said “Is that it?”, and was ready to get up and leave. But when Roman [Kroitor] made it clear that he was not satisfied yet, it seem to touch Rain’s professional pride in the right way,” and so they recorded it again.

Ultimately, Rain’s work on the film knit it together in a way that was completely satisfying to the NFB. Daly said of Rain’s re-recording of the narration: “his changed state of emotion brought forth the tones of voice that can still bring shivers down my spine.”

(William Shatner narrated a plodding NASA-funded knockoff of Universe in 1976 titled, imaginatively, The Universe. Rain had shared the Stratford stage several times with him in the mid 1950s, so, if one is keeping count, that means that HAL 9000 worked with both Obi-Wan Kenobi and Captain Kirk).

“IF YOU’D LIKE TO HEAR IT, I CAN SING IT FOR YOU”

In late 1967, in a studio at MGM Borehamwood outside of London, Kubrick and Rain sat a few feet apart, to record HAL’s dialogue. Kubrick made only a few comments during the session.

Rain hadn’t seen a frame of the film, then well into its final stages of post-production. He never met any of his co-stars–and hasn’t since. He didn’t know much of what the film was about, or that the role he was about to play was to be its most significant. He hadn’t even been hired to play HAL, but to provide some narration for a prologue, an idea later dropped by Kubrick.

Balsam had already recorded HAL’s dialogue more than a year prior, but Kubrick said to Rain “I’m having trouble with what I’ve got in the can, would you play the computer?”

Rain agreed to switch from narrator to actor. But Rain told me “If you could have been a ghost at the recording you would have thought it was a load of rubbish”.

In 1965, when Rain was playing another Hal, Prince Hal in Henry IV at Stratford, he told CBC Radio that he loved doing it because he knew Shakespeare so well, and understood the character’s evolution. “It’s marvellous to be able to work a character through from beginning to end.” There was no time for that in his collaboration with Kubrick.

The Stanley Kubrick Archive, one of the most comprehensive repositories of any film director’s documents, sits unimposingly in the basement of the University of the Arts London. The materials were previously housed in the filmmaker’s 17th century estate outside London, mostly in thousands of banker’s boxes made to his specifications. Kubrick’s notebooks, script drafts, business correspondence, a memo about the possibility of selling HAL 9000 buttons to fans—-there’s a lot here.

The Archive’s tiny reading room is wittily decorated to match the space station in 2001, with distinctive red chairs and shiny white surfaces, but minus the gravity-defying curved floors. In the archive’s files sits the transcript of the HAL 9000 recording session, with every take that Rain did of the dialogue, and Kubrick’s stage directions to him. Kubrick didn’t say much.

In a way, Rain was an actor playing a computer who could be an actor; Kubrick had, in the film’s development, described the computer’s ability to “fake emotion and pain.”

Rain wasn’t intimidated (he described the filmmaker as “a charming man. Most courteous to work with”), but he told me that he felt “there was absolute dictatorship by Kubrick—-his sound recordists were terrified of him, but when asked, agreed with me that my voice level had been dropping, so we stopped in the afternoon, to continue the next day,” finishing the task in less than 10 hours total.

HAL’s lines are both technocratic and sadly human. One has to imagine what they seemed like to Rain in that recording studio, out of context and performed for an audience of one, Stanley Kubrick.

Kubrick, according to the transcript, says, here and there, to Rain:

-“try it again a little quicker and more professional”

-“a little more concerned”

-“sound a little more like it’s a peculiar request”

-“just try it closer and more depressed”

-“even softer and kind of in the depths”.

And in a section where HAL won’t let Bowman back into the spaceship, Kubrick instructs Rain this way: “try a little more dandy.” (The line in question, which was not used, is: “there is no problem”).

The use of the word ‘dandy’ by the director wouldn’t have been known at the time, but in a 1970 interview Joseph Gelmis raised the question of HAL’s sexuality with Kubrick: “some critics have detected in HAL’s wheedling voice an undertone of homosexuality. Was that intended?”

Kubrick: “No. I think it’s become something of a parlor game for some people to read that kind of thing into everything they encounter. HAL was a ‘straight’ computer.”

Much of Kubrick’s crafting of HAL didn’t happen in the recording studio, but in the editing room, where so much material was pruned out. Rain’s breaths were also removed in post-production to give HAL an unearthly quality audiences wouldn’t notice, but would feel.

Dave Larson shares the perspective of a crew member, Colin Cantwell (from the special photographic effects unit), who watched Kubrick edit the famous ‘death’ scene, where HAL is disconnected, and pleads for his ‘life’, before singing the old tune “Daisy Bell” as his mind decays. “Despair and die,” one might say.

“He told me that he started crying about how sensitive Kubrick had been about the computer. Basically, you’re hearing Rain’s neuter-quality voice that belies the gravity of what’s happening and you’re watching a motionless shot of a glass lens with a light behind it” (HAL’s ‘eye’). Yet you’re feeling a tremendous amount of sympathy for HAL as he is destroyed in a rare and unusual way that might be akin to the gradual loss of identity we experience in Alzheimer’s. Just horrible. And for the time of the release in the late ’60’s totally shocking and astounding.”

Larson further underlines the way in which Kubrick took Rain’s recording, and, indeed, all of the raw dialogue for the film, and transformed it. “The main thing that interests me is the editing that Kubrick did on all the dialogue…like some of the Kustom hot rod people…he chopped and channelled the whole production in a minimalist way, so it was smooth as a work of art.”

“HAL IS ALIVE AND LIVING IN CANADA.”

Despite 2001’s success, and even as the character of HAL remained indelible in filmgoers’ minds, Rain’s visibility as HAL faded in the years after its release, his role in it acquiring some mystery as he returned to the stage, his face unknown to moviegoers. Years later Rain said, “It’s not that I haven’t wanted to do movies, it’s just that I’ve never been approached. People seem to think that when you do classical things you can’t do anything else. Well that’s rubbish of course.”

In an interview with the Toronto Telegram right after the film’s release, Kubrick described Rain’s work as HAL as “absolutely superb” and when asked if he would cast Rain again, replied “Sure. Maybe next time I’ll show him in the flesh….but it will be a non-speaking part. That would perfectly complete the circle.”

Rain may have wanted to have nothing more to do with HAL, but as a working actor, HAL’s fame attracted the occasional quick gig. In the 70s and 80s, Rain for example, reprised HAL for radio commercials for rock and roll laser light shows at the McLaughlin Planetarium.

He showed his comic side in an appearance as HAL as the sardonic sidekick to Rick Moranis’ trapped-in-outer space Merv Griffin on SCTV’s The Merv Griffin Show: The Special Edition: “Well Merv, after 2001, I waited for Stanley to exercise his option on a sequel my agent told me was in the bag. But Stanley immediately he went on to A Clockwork Orange and I wasn’t included. His next picture was Barry Lyndon, and of course I wasn’t right for that. Well then I got sick, and by the time I recovered, Nicholson had gotten my part in The Shining.”

Producer Marc Giacomelli, who worked with Rain on the SCTV episode, and radio commercials, found Rain to be a “super pro. He did it on first take.” But it meant little to Rain, and so a market for sound-alikes emerged. Giacomelli: “there were a number of times there was a radio show or something where we wanted him to do HAL, and couldn’t get him. There are a couple of actors in town who made decent money–probably more than Douglas Rain made off his voice–doing Douglas Rain. “

The call did come to play HAL again, but not from Kubrick.

Kubrick wasn’t ever interested in sequels to his work, and even had most of the sets and props from 2001 destroyed so they couldn’t be used in any cheap sci-fi films to follow.

But he gave his blessing, of sorts, to director Peter Hyams’ plan in the early 1980s to create a follow-up film, 2010: The Year We Make Contact. Hyams collaborated with Arthur C. Clarke, and tried, with some difficulty, to find Rain to reprise his role as HAL. “I spoke with Douglas Rain today. He does sound like HAL. HAL is alive and living in Canada.”

Hyams flew Rain to Los Angeles for one day of recording. “I wanted to record all of the HAL dialogue in advance of shooting,” –the opposite of what Kubrick had done. Rain’s classical training didn’t impress Hyams and he didn’t see it as contributing to the re-creation of HAL. “I felt he had to lose all that Shakespearean stuff.”

As the recording session began, “it just wasn’t right at first, he was just talking like a human being”. So he gave Rain perhaps one of the least motivating director’s notes ever given to an actor: “I said to him ‘say it like you’ve been lobotomized.’” Hyams then played a portion of the 2001 HAL dialogue for him, and Rain gathered his thoughts. Hyams remembers that “when Rain spoke again as HAL, the sound recordist jumped in the air as Rain nailed it. HAL was in the room”.

Bob Balaban, who played HAL’s creator Dr. R. Chandra in 2010, said in an interview that Hyams played the recording of Rain’s voice for him when he did his scenes. “Strangely enough, I had no sense of acting with a recording. Rain is a very good actor. As far as I was concerned, if felt like he changed his performance from take to take.”

Rain wasn’t interested in ever playing HAL again–even for Steve Jobs.

Commercial producer Ken Segall tried to get Rain for an Apple commercial in 1999, but when he refused, the call went out for HAL wannabes. Segall thought, at the time, that “surely Hollywood was brimming with talent who could do an admirable HAL. Well, not so fast. We had a casting agent put out a call for HAL imitators, and the results were disappointing. Reel after reel came in, and a good HAL was harder to find than I thought.”

Finally, American actor Tom Kane nailed it, Segall learning from him “that an essential part of HAL’s voice was the slight touch of a Canadian accent. It hadn’t struck me, but Rain was indeed a Canadian actor, and even when playing a computer, elements of his accent came through.” For Kane, Rain’s voice is the ultimate example of the “Canadian lack of an accent. Rather than something that’s there, it’s something that’s not there.”

“THERE ARE SOME EXTREMELY ODD THINGS ABOUT THIS MISSION.”

The Festival Theatre in Stratford, is, in diagram form, weirdly similar to the layout of 2001’s centrifuge onboard the Discovery. The theatre’s stage thrusts into the auditorium, and has semi-circle seating and ‘voms’ (passages called vomitoria for the actors to make sometimes surprising entrances and dramatic exits amidst the audience). On the ship, HAL is everywhere, an ever-present red eye and perfectly modulated voice. On the stage where Douglas Rain strode for decades, he projected his voice with just the right volume and emphasis to an audience of as many as 1,800 people, none of whom are more than 65 feet from the stage.

Martha Henry tells the story of a particular ‘conversation’ Rain had on that stage.

“Douglas played Angelo in Measure For Measure in 1976 for director Robin Phillips. He and Robin didn’t mesh well, and although there was no overt friction, Robin could never find the ‘key’ to Douglas, and I don’t think Douglas ever trusted Robin.

But one day, in the midst of a complex rehearsal process, Robin asked Douglas (I believe this was meant as a rather testy impossible challenge) to exit down right into the vom, but to leave his voice onstage. Douglas said not a word to this, but went back into the scene, exited down right…and left his voice onstage. To his great credit, Robin himself would tell that story. Several actors witnessed it. No one has ever been able to say how he did it.”

It’s that voice again.

When he speaks the final line in Universe, Rain quietly reaches for something immense and contemplative, something deeply human. But it is also something that, from our distance decades after 2001: A Space Odyssey first appeared, could also evoke the curiosity an artificial intelligence like HAL 9000 might have: “In all of time, on all the planets of all the galaxies in space, what civilizations have risen, looked into the night, seen what we see, asked the questions that we ask?”

Update (11/27/2018):

Douglas Rain died, at age 90, on November 11, the 50th anniversary of 2001: A Space Odyssey this year having been noted and celebrated by just about everyone except him.

Thousands of news items and obituaries across the globe marked his passing, and though most went with the seemingly inevitable take —- “the voice of HAL 9000 has died” – many presented a fuller picture of the actor, presenting to readers, perhaps for the first time, a face to the voice. It must have been startling to those who only knew him as a luminous red dot onboard the Discovery spacecraft in 2001 to see him, in a black and white photo, as a pensive young actor in Shakespearean garb, years before at Stratford.

One commenter, however, objected to the frequent use by media outlets of the 2001 computer red light to represent Rain in his death —- it was indeed a role he played, but though he inhabited that device, it didn’t inform his performance, and so it shouldn’t represent him.

The Stratford Festival, not surprisingly, did the best job of defining Rain’s work as HAL as having “made an indelible mark on popular culture,” and one wonders what he might have offered as an on-screen actor to Kubrick and other great directors.

Stratford artistic director Antoni Cimilino drew a straight line between Rain and his most famous character, a line many didn’t perceive: “Douglas shared many of the same qualities as Kubrick’s iconic creation: precision, strength of steel, enigma and infinite intelligence, as well as a wicked sense of humour.”

Rain’s relative invisibility lead to an error, one much-repeated over the years, being compounded in the notices of his passing: that he also played the voice of a computer in the science-fiction comedy, Woody Allen’s Sleeper. As Rain’s sons put it: “for those of us that know his voice, well, that is not Douglas Rain speaking but another actor doing an attempted imitation of HAL’s voice…but we do admit it does make a very nice story.”

Rain might be slightly bemused at no one really knowing whether he was in a Woody Allen film or not. But at a time when Elon Musk is musing about moving to Mars as soon as he can, Rain likely wouldn’t care that scientists are already working on a HAL-style AI which can run a Mars colony “minus the paranoia and betrayal.” Without those qualities, it does sound a bit un-Shakespearean.

-Gerry Flahive