“I don’t want to make a cartoon,” director Ryan White recalls telling Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) during early discussions for Good Night Oppy. “But if you can make this film photo real, because we have hundreds of thousands of photographs and we know what every day of the journey looked like, we can build Mars from the ground up based on this information.”

White takes audiences to Mars in the thrilling adventure of Good Night Oppy. Mixing cutting-edge visual effects and meticulous research, the film recreates the Martian landscape with astonishing realism. These details come thanks to the key subjects of Good Night Oppy, the Mars rovers Spirit and Opportunity. The film recounts the journey in which the robots, now “deceased,” roamed Mars for years and captivated the world. White draws upon the arsenal of information the “sisters” collected for NASA on a 2004 mission that was expected to last only 90 days, but surprisingly spanned 15 years.

The scope of the film marks a departure for White following doc portraits like Ask Dr. Ruth and Good Ol’ Freda, and verité-driven works like The Case Against 8. White admits that the learning curve for Good Night Oppy was steep, especially since his initial meeting with Steven Spielberg’s Amblin Entertainment was on March 12, 2020. The day after convincing them to do a VFX-driven journey, White recalls getting the notice that Los Angeles was in lockdown.

“I like choosing films that have aspects that are totally new to me,” observes White. “It’s not why I choose stories, but if a story has some sort of filmmaking aspect that I’m not familiar with, I want to throw myself in those types of situations where I’m totally underwater and figuring it out.”

Bringing Oppy into the Present

White adds that he keeps his films in the present tense and isn’t interested in retrospective stories. Despite charting a mission that began blasted off in 2004, over 1000 hours of photos and footage let him tell the rovers’ story in the moment. There are moments of great suspense as rovers get stuck in the sand and a team of NASA researchers put their heads together to community an escape plan on Martian terrain.

“My addiction to documentary filmmaking has always been about being with someone or a group of people on a remarkable journey,” notes White. “I get to be on the sidelines with my camera. I love that as a career. This film was a big departure for me in that the beginning, and middle, and end had already happened.”

The present tense also unfolds through the active voiceover by Angela Bassett, who recounts the mission logs throughout the journey. “I didn’t write words for Angela to be like Morgan Freeman in March of the Penguins,” says White. “I scripted them out of diary entries that NASA wrote every day. She’s playing the voice of NASA. The real boon of those diaries was they were written daily; they weren’t written retrospectively. When we’re in an emergency, a crisis, or even a joyful discovery, they’re written with real drama and suspense. That allowed us to keep the audience on the adventure.”

The film takes audiences along the journey as the story cuts from the rovers on Mars to the scientists and engineers at NASA. Archival footage and new interviews with figures from mission control distill the science in accessible terms. However, the human characters inject grand emotional beats to the story of Spirit and Opportunity. They speak of them in human terms, and the robots’ design invites onlookers to anthropomorphize them. Good Night Oppy is a feat of exploration and adventure at heart as the rovers chart into unknown terrain.

Life on Mars

The production of Good Night Oppy has endearing parallels to the rovers’ journey into the unknown. For White, learning a new production method at the onset of lockdowns involved guidance and teamwork from afar, albeit with more autonomy than Spirit and Opportunity have. “It was like VFX 101,” says White, who says that ILM’s team taught him techniques remotely. They also offered examples from their catalogue as guidance to shape his vision for a photo-realistic Mars. “I just learned on the job,” admits White. “I hired an amazing associate producer, Dominique Hessert Owens, who taught herself storyboarding and VFX.”

Audiences observe the materials from which White and his team drew. Grainy black-and-white images from the rovers, including a selfie that brings a tear to the eye, offer a mosaic of the red planet, but it’s only in the VFX expeditions that one gets a full 360° view of Mars.

White explains that they storyboarded for over a year with artist Josh Sheppard (The Batman, Lincoln) to lay the groundwork for those VFX sequences. “We would have meetings over Zoom that was like Win Lose or Draw,” laughs White. “Josh is an amazing artist. He can sketch things in 15 seconds. He would sketch something and hold it up and I’d be like, ‘Oh no, what if we bring the camera around here?’” From these sketches, White says the VFX wizards at Amblin and ILM then created the images of Mars, which impressed even the NASA team.

To Infinity, and Beyond

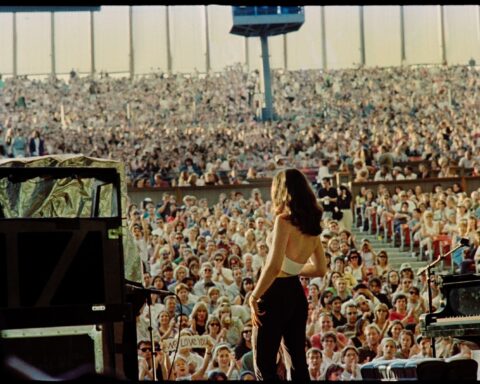

The grand VFX of Good Night Oppy, moreover, have played on massive screens usually reserved for Marvel movies. (During TIFF, Oppy premiered at Toronto’s Cinesphere, which boasts an IMAX screen 80-feet wide.) Although the project will ultimately reach most of its audience on Prime Video, White says the vision was always to go big. “We built it for the big screen and we did the sound design for the big screen. We didn’t scale things down knowing that most people will probably watch it at home,” says White.

The director acknowledges that home video specs vary from house to house, but also that the current marketplace demands pragmatism. “We’re coming out of COVID and there are very few screens these days that don’t have some mega film on it,” observes White. “There are fewer screens for documentaries, so it’s a matter of having the best of both worlds.”

White makes the case the accessibility of Good Night Oppy ultimately deserves the “pushing boundaries” descriptor used for the VFX. “My favorite screenings so far have been ones full of children or with parents bringing their kids to film festivals,” notes White. “The kid doesn’t even know they’ve watched a documentary,” he laughs. He finds another adventure awaits his audiences when they learn the story came from life, rather than imagination.

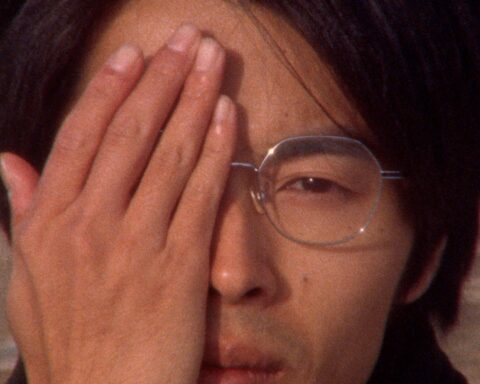

The all-ages appeal reflects the trio of films White used for comparison during production. He says the used the Oscar-winning documentary March of the Penguins in terms of the film’s audience—it grossed over $100 million thanks to its multi-generational appear. For the film’s heart, though, White says he looked to Steven Spielberg’s classic E.T. and Spike Jonze’s Her, in which Joaquin Phoenix falls in love with an operating system voice by Scarlett Johansson. “I wanted this film to be an examination of that connection between human and nonhuman,” says White

Born to Be Wild

While Oppy is largely drawing raves, White says he hasn’t heard industry pushback regarding the role of VFX in documentary. “There was that same conversation around Flee last year,” observes White. “I think Flee‘s a straight up doc. He just couldn’t shoot the story.”

White adds that, as with Flee, the images in Good Night Oppy are rooted in non-fiction. It’s simply a facet of filmmaking to mine creative resources. “I love when my friends are able to use a filmmaker’s toolkit in a way that wasn’t relegated to documentary filmmakers 20 years ago,” says White. “Those visual effects are deeply steeped in what Mars actually looks like. We just couldn’t go there and shoot it ourselves. Documentaries use animation all the time and have for a very long time. I’d be happy to see my friends access visual effects or new types of sound design. If it helps us tell our story better, why can’t we as documentary filmmakers have access to what all other filmmakers have?”