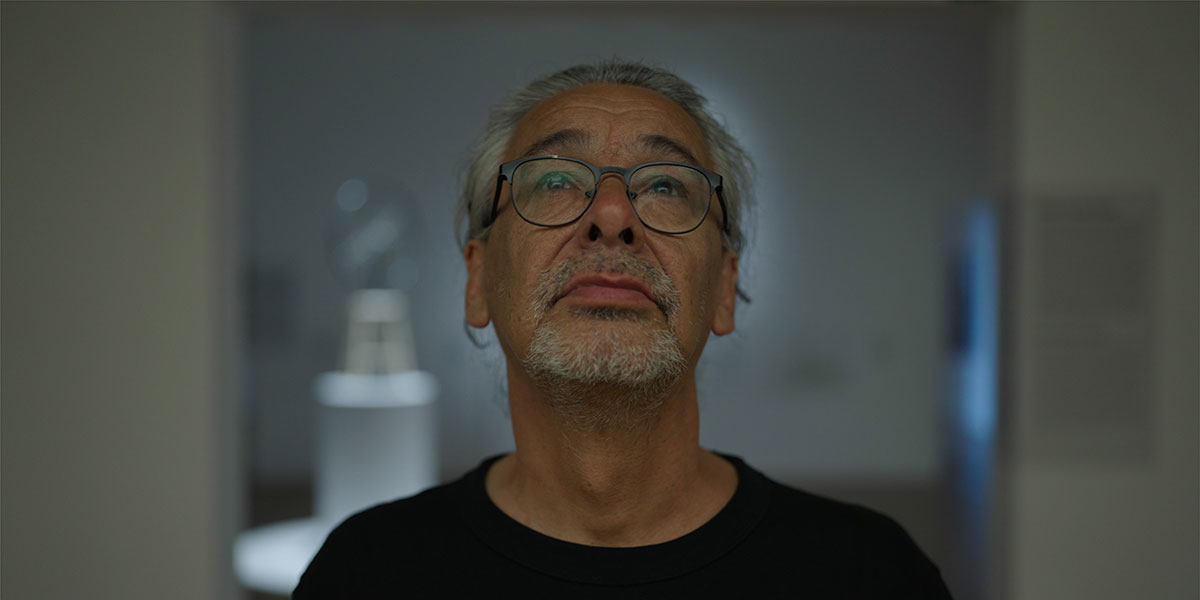

Neil Diamond is a Cree filmmaker, who made a huge impact with Reel Injun, a documentary about the negative “Indian” stereotypes that so permeate Western society that even the filmmaker as a child wanted to be a cowboy, not himself, when playing with friends. Reel Injun won three Gemini Awards including for best director and went on to win a Peabody Award. Diamond has continued to work with Rezolution Pictures, making such films as The Last Explorer, One More River, Heavy Metal: A Mining Disaster in Northern Quebec, Cree Spoken Here, and Red Fever. His new film So Surreal: Behind the Masks, co-directed by Joanne Robertson, explores the strange but intense relationship between Surrealism and the masks of the Yup’ik ‘and Kwakwaka’wakw nations and how that commingling came to pass. It’s about cultural appropriation, art and dream imagery.

POV editor Marc Glassman was pleased to talk with Neil Diamond about the film—and kudos to Joanne Robertson for her part in this incisive documentary.

POV: Marc Glassman

ND: Neil Diamond

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

POV: How did this film start? What was your reaction when you found out about the Surrealists appropriating masks from the Yup’ik and Kwakwaka’wakw nations and using it in their art?

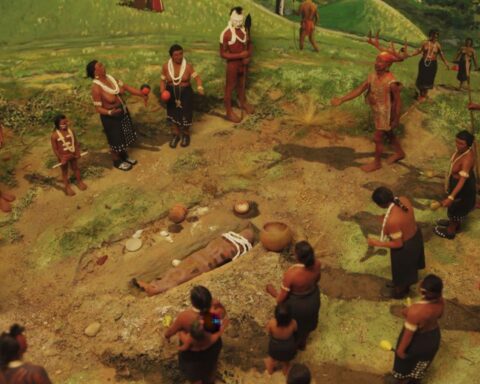

ND: Surprised. That’s something I learned while when we started filming. The masks are an important part of our history. They influenced sport, fashion, politics, and just being aware of one’s environment and taking care of nature. I hesitate in using the word art when I’m referring to the masks, because they weren’t considered like that, especially the Yup’ik masks. They were ceremonial objects, and there was a heavy spiritual element in the Yup’ik relationship to the masks. They still believe that they hold a lot of power. It was only shamans who wore them, and they claimed that they journeyed to the other side of reality.

Even the Kwakwaka’wakw masks were never displayed except in ceremony. As soon as the potlatch ceremony was over, they were put away in boxes, and they weren’t taken out again until the next ceremony was held. A very interesting thing I learned, and I knew this from my own culture, the Cree, is that there’s no word for art. Most native languages don’t have a word for art.

POV: It’s funny because when you think of the cultures of so many Indigenous and Inuit nations. My partner has spent a lot of time with the Inuit, and it seems as if every other person is an artist.

ND: Yeah. It’s true. Yeah. My father, I only saw him as an artist. He was a canoe builder. He made his own snowshoes, his own shovel. He created all these things.

POV: Is it because it is so inherent to be able to do the work well that there is no distinction between creating a shovel or a mask and seeing that there’s something intrinsically beautiful about it?

ND: They believe that the objects that they created in order for them to survive had to have a power behind them. What the Cree carvers would do, if they were carving snowshoes, they would have a chant for them. They would sing to whatever they’re creating and try to make it as beautiful as possible. They would have their own clothing for a hunt. There was a saying that “If the hunt sees you, you’ll have a connection to the animals you depend on to survive.”

POV: Is it because white people in general don’t understand the spirit world? I think about it in terms of the Native ritual of killing an animal and thanking the animal. That’s something a white person wouldn’t do.

ND: Yeah, that’s true. And it’s still done today. If they kill the moose, they will usually give it tobacco as a gift, thanking this animal spirit for giving itself up so you could survive.

POV: Surrealism isn’t spiritual, but it certainly is about the movement between different planes of existence. Do you feel a connection between Yup’ik shamanism and some of the surrealist concepts?

ND: Yeah, I think there is a real connection. What surrealists were saying is exactly how the Yup’ik felt about these masks. Not so much the Kwakwaka’wakw, which just tells their history, and doesn’t really have that spiritual element in their use of masks. But the Yup’ik shamans would go into a trance and claim that they were able to see the other side, which is something that the Surrealists were interested in. Dreams and automatic writing, and there is a real connection there between the two.

POV: Do you feel that the potlatch is something that is almost inexplicable to Western culture?

ND: Yeah. It’s so different from the way white people treasure their possessions. I’m not a wealthy person, but when you give something away, there’s a feeling you get that’s really different. I remember once walking on a street in Montreal, and there was a man sitting there, who was obviously very hungry. I reached into my pocket and gave him $5. As I walked away, I just felt this shiver go through my body. I don’t know why but I felt good.

POV: I think that’s exactly the reason why the colonial powers wanted to get rid of the potlach. What were Native people doing? It seemed that they were fighting against Canada and capitalism, even though I’m sure it wasn’t deliberate.

ND: It’s tragic what happened, making the potlach illegal for decades.

POV: And that’s when the masks were sold or given away to museums and art galleries in the East Coast and Europe, far away from B.C.

ND: A lot of them are like in museum basements across the world. Apparently, the biggest collection is in Germany. But we went to Paris, where the Surrealists returned after the Second World War.

POV: How important was it to have an art dealer like Donald Ellis involved in the search for long-gone ceremonial masks? He seems to have gone through some kind of transformation in his understanding of the culture.

ND: He was a boy collector. Through the years, I guess he went through a change. He felt it wasn’t right for these people’s possessions to end up in museums and private collections, because they were stolen. They were sold and confiscated. Yes, Donald is an interesting character.

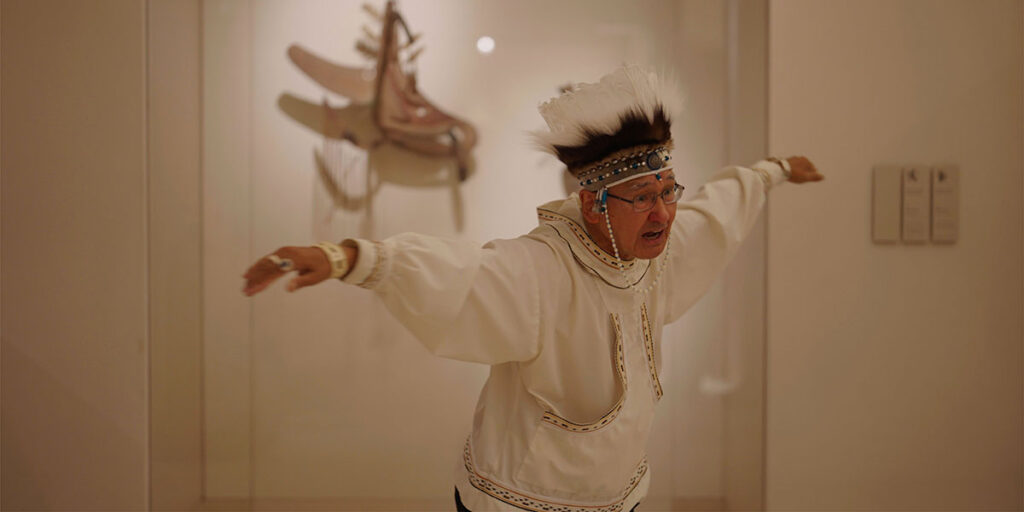

POV: It almost feels as if this is an anti-heist movie. You’ve got a disparate group of people on a mission. You’re part of it and Donald and Chuna McIntyre, who ran the Yup’ik Singers and Dancers troupe too.

ND: Could we have turned this into a fiction? Yeah. What we did, searching for masks, was an investigation. Like a detective story. And my co-director Joanne Robertson did a lot of the detective work. She’s the one who hired a private investigator to help us find a very important mask.

POV: What’s your feeling about Surrealism now? What’s your appreciation of it?

ND: I knew very little about Surrealism before making this film. I knew Salvador Dalí and Man Ray but I had never studied art history. I appreciate them now. They connect to Cree culture. My father would interpret dreams, and I’ve had some dreams, too. It’s a spiritual gift that you get from your relationship to nature. I respect Surrealism and how it relates to the dream world.

So Surreal: Behind the Masks premiered at TIFF 2024.

Read more about the film in additional interview with Diamond and Robertson in issue #122.

Get more coverage from this year’s festival here.