When POV Magazine asked me to consider whether the documentary was Canada’s national art form it got me wondering if other countries identified themselves with forms of art. Is it movies for America, opera for Italy, theatre for England, ballet for Russia? Perhaps not being a native-born Canadian, I have never before considered such a proposition.

My early experience of Canada was formed as an immigrant living among other recent arrivals from Europe making their way into the mainstream. My family came to live and work in the inner city of Toronto and eventually moved to the suburbs. It was the Canadian Dream of working hard and enjoying the social mobility that came with success. As a baby boomer, I benefitted from the post-war expansion of the economy and received an inexpensive university education. Working-class immigrants, like my parents, could realize the dream of sending their kids to university without it breaking the bank. My parents didn’t care what career my sister and I chose as long as we worked hard and stayed in school. I’m acutely aware that parents today may not share the same optimism my mom and dad had in those days.

In grade school, I remember the teacher showing documentaries in class. As a captive audience your two options were to either fall asleep or to watch. I watched. When I was 14, I regularly visited the library that had just been built in our corner of desolate, suburban Downsview. I eventually worked my way through the entire photography section, going back again and again to the books on landscape, photojournalism and portraiture. It was photojournalism that captured my attention—the work of the Magnum photographers such as Cartier-Bresson, Eugene Smith and especially Robert Capa. I loved his black and white images of the Spanish Civil War and D-Day. It put me upfront in a drama, imagining what had happened just before and just after that instant was frozen in time. That’s when I developed a passion for documentary photography.

It wasn’t until my second year in York University’s film program that I got serious about documentary filmmaking. There was only one course on documentary available at the time, with Professor John Katz. He was showing a lot of cinema vérité, films that came the closest to photojournalism. Technology had recently changed and all of a sudden you could do with motion and sound what you could previously have only done with a still camera. After I completed that year, I asked John if I could take his course again, but only if he showed new films. He assured me that every semester he made a point of screening the newest documentaries along with the classics.

It turned out John needed someone who could do reel changes on the 16mm Kodak Pageant Arc projectors. I agreed to double as the projectionist in exchange for the tuition and course credit. That’s when my interest in documentary took off. I saw Allan King’s Warrendale and great American works like Salesman, High School, Primary by the likes of the Maysles brothers, D.A. Pennebaker, Fred Wiseman, and Terry Filgate. When I saw the Maysles’ Gimme Shelter, combining photojournalism and rock & roll, the documentary bug bit—and it’s still with me today. After school, I started an independent production company, convinced that audiences would want to see true stories about art, drama and the history of life at the end of the 20th century.

In the early ’90s, TVO, Ontario’s public broadcaster, recruited me as its first commissioning editor. It was a fortuitous opportunity to be creatively involved with a large slate of independent films rather than the handful I was making as an independent producer. It was a tumultuous time in Canada. We were undergoing great cultural change as a response to the worldwide advances of technology, deregulation and globalization. Immigrants were arriving in larger numbers from Asia than they were from Europe or the U.K., and Canadians were trying to sort out what kind of society we were in the process of becoming.

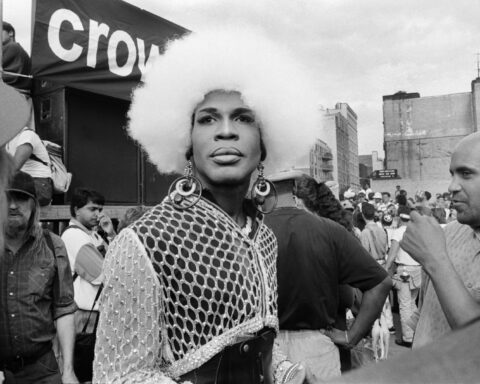

Looking back on it now, those times seem almost unreal. The first project thrown in my lap was Michael Ignatieff’s Blood and Belonging, a co-production with BBC Wales. The series was Michael’s first-hand account of the global struggle between ethnic and civic nationalism in places such as war-torn former Yugoslavia. I commissioned films that promoted the recognition of Canada’s First Nations as a people with fundamental rights, since the concept wasn’t broadly accepted at the time; and films that documented the fight of the gay community for freedom from persecution, as laws were harsh and intrusive. Another controversial issue examined by filmmakers was reproductive rights for women. Neither the government nor the courts had come up with effective measures that reflected the changing attitudes of Canadian society.

My commissions from that period that readily come to mind are Jane Rule: Fictions and Other Truths, by Lynne Fernie and Aerlyn Weissman; Anishinabe: We the People, an anthology series co-commissioned with Dan Gaspe, and John Zaritsky’s Murder on Abortion Row. Before laws can change, mainstream society has to move forward. Documentary filmmakers helped to shift attitudes in the general public, which then motivated politicians to amend laws to bring us closer to the concept of universal equality. We’ve come a long way.

At TVO, I encouraged documentarians who were trying to make a difference. I recall working with Joel Bakan and Mark Achbar on The Corporation. Other filmmakers had worked over the institutions of church and state, but somehow this increasingly transnational institution that was having a tremendous influence on our daily lives went unexamined. At the time, the film was—I won’t say radical, but it was out there. Now with the 2008 financial crisis still wreaking havoc on global economies, The Corporation seems almost prescient. While the one percent has done extremely well, the rest of society has suffered. I can’t imagine what it would have been like for my parents if that level of economic inequality existed when they were young immigrants with a family to raise. The Corporation was ahead of its time. To this day, it is still being screened and discussed and debated.

One of the hardest subjects to do well in film is economics. The Corporation was one of the few that succeeded. It’s a point-of-view documentary where the filmmakers take poetic licence by subjecting the corporation to a psychology test and diagnosing it as a psychopath. The audience understands it’s a metaphor for an examination of an abstract concept. Now we’ve got new work, like the Oscar-winning Inside Job, examining the forces and players responsible for millions of people losing their homes, their pensions and their jobs. Abstract financial concepts like credit default swaps and collateralized debt obligations have concrete consequences. Documentaries have demonstrated their ability to illustrate such concepts in a form a great many people can comprehend.

A documentary director who bridges abstract concepts in art and politics is Jennifer Baichwal. I was fortunate to work with her on a number of films, starting with her first feature, Let It Come Down, a profile of the writer and composer Paul Bowles.

The last time we worked together was on her most popular film, Manufactured Landscapes. It was of particular interest to me because it combined the subjects of photography, economics and the environment all in one work. It’s ostensibly a portrait of an artist, but more than that it’s how art can access deep insights on big subjects: how economic development can degrade the environment, like the ship breakers of Bangladesh; or displace millions of people for the construction of the massive Three Gorges Dam in China. The issues are explored through the formal photography of Ed Burtynsky. Although these same issues are covered in the news all the time it’s difficult for the public to meaningfully engage as there is too much information and too little insight. Every once in a while a creative work of art succeeds in holding people’s attention long enough to get them thinking. That’s the power of creative talent—like Jennifer’s in Manufactured Landscapes.

This brings me to the great filmmaker Allan King. Back at university, his pioneering feature Warrendale had moved me, and A Married Couple was the very first documentary feature I had ever paid money to see in a commercial theatre, Toronto’s Cinecity. Much later, I got to work with him. I used to tell Allan that if my only legacy is to be known as the guy who brought the great master back to documentary, then I will have had a successful career as a commissioning editor. We always had a good laugh because of the serendipitous way it came about.

Allan had come to see me to pitch an idea for a film on a process for reconciliation in a former Soviet bloc country. That turned out to be Dragon’s Egg. I was primarily interested in licensing A Married Couple, which he readily agreed to as long as it was shown uncut. Then he asked why I didn’t also acquire Warrendale as it had never been broadcast in Canada. So 25 years after the film had been commissioned for and banned by the national public broadcaster, I had the good fortune to premier Warrendale on TVO—uncut and commercial-free, of course.

Aside from the mountain of publicity it generated, Warrendale broke all audience records for a documentary on our network. That’s when I offered him carte blanche on his next project. A year later he proposed a feature documentary about the end of life, the film I think became his greatest work, Dying at Grace. When we won the Academy of Canadian Cinema and Television’s Donald Brittain Award for best social-issue documentary, I got to share the stage with the master: a special moment with a singular talent.

Working with Allan for several precious years influenced my own views on life. Funny thing, although we would meet and talk for hours at a time, we rarely talked about filmmaking. Allan would speak about philosophy, about the dynamics of interpersonal relationships, about his fear of losing his memory. We talked about art and just about everything else. Allan documented the human condition: his work was about the profound meaning of life, not about the politics of the moment. His second coming to the genre coincided with documentary’s arrival in the media mainstream. So it was wonderful to see Allan lionized in Canada and around the world as a master of the art of documentary.

As CEO of British Columbia’s Knowledge Network, I think about how the process of filmmaking has changed. Image capture is no longer the big deal it once was. At one time, it was complicated and expensive and could be performed only by skilled professionals. It was precious and invaluable. Now anybody with a mobile phone can record motion picture–quality images and sound. It’s overwhelming and has little or no value in and of itself. What does have value is synthesis or storytelling. That comes from the mind and hands of an artist. Talent and insight are required to take raw images and sound and, with some luck, shape them into a form that acquires value through meaning and stands the test of time. That’s why in the creative documentary (and fiction, because no form of storytelling has a monopoly on the truth) it’s the artist who is central to the work.

Contemporary documentarians are driven by the same principles and desires as previous generations. Filmmakers continue to examine the issues of the day, to challenge conventional wisdom on human rights, climate change, and inequality. Making documentaries for television and the Internet, for festivals and theatrical distribution is on the rise—even if the money to make the work continues to be difficult to find.

After a long career devoted to documentary, do I think that it is intrinsic to the Canadian way of life? Yes, I do. Other art forms have also contributed to our identity. But through the power of the moving picture, the documentary has shaped the Canada of the heart and mind and helped bridge the gap between marginalized members of our society and the mainstream. It is the Canada I believe in. Is it Canada’s national art form? All I can say is we wouldn’t be the same without it.