West of the Jordan River

(Israel/France, 88 min.)

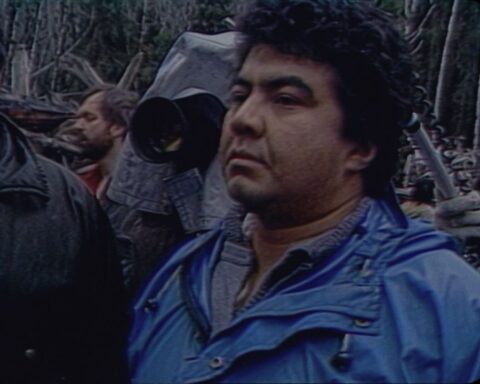

Dir. Amos Gitai

In 1982, a renowned Israeli director Amos Gitai visited the occupied territories of the Gaza Strip and the West Bank to film Field Diary, a documentary that chronicles the region’s escalating tensions. At the time, Gitai and his crew were deeply concerned about the daring vehemence of the right-wing Israeli movement.

In his new documentary, West of the Jordan River, which has its North American premiere at VIFF, Gitai resumes the discussion he started in the 1980s with vigor, resilience and determination. Through multiple interviews with journalists, activists, civilians and politicians, Gitai voices a wide range of concerns, ideas and forewarnings that have infiltrated the area. With his attentive dialogues and provocative conversations, the filmmaker makes the audience ponder the permeating conflict between Israel and Palestine.

The film mostly features images and voices of the present with a few scenes dating back to 1994 including the interviews Gitai shot with former Israeli prime minister Yitzhak Rabin prior to his assassination. Advocating for a peaceful solution to the Israel-Palestine conflict, Rabin was assassinated by a right-wing Jewish extremist in 1995. Since then, the attempts to restore the once-affable Israel-Palestine ties have been eradicated. Through offering the footage of Gitai’s interviews with Rabin in 1994, the filmmaker pays tribute to the former leader’s attempts to build fertile dialogue and condemns the contemporary Israeli leadership.

While Gitai mostly articulates the views of the liberal Jewish-Arab community, he interviews a few right-wing Israelis, such as deputy minister of foreign affairs Tzipi Hotovely. Like most of the contemporary Israeli politicians, Hotovely doesn’t follow Rabin’s legacy of peaceful negotiations. She opposes the two-state solution and rejects to use the term “occupation,” a growing tendency among the rightward movement.

Hotovely’s views illustrate the qualms of the left-wing journalists and members of NGO organizations with whom Gitai also speaks. An Israeli journalist, Ari Shavit, for instance, dreads that the current Israeli legislations will bring the country to an end. According to Shavit, the Israeli colonization of the Palestinian land contradicts Jewish and Zionist values. He argues that if Israel doesn’t change its policy in the next ten years, it will “pass the point of no return,” which is the recurrent expression throughout the film.

Gitai approaches all his subjects, Palestinians and Israelis, with straightforward and explicit questions. His alluring personality and palpable passion for the topic enlivens the film, which otherwise might have come across as uninteresting. While the structure of his documentary is pretty trivial, consisting almost solely of in-person interviews and conversations, Gitai’s resilient pursuit of answers is captivating and resonant.

Gitai’s portrait of the current Israel-Palestine relations is both enrapturing and harrowing due to its high level of pragmatism. Gitai doesn’t spare any time on aesthetic components of his film. Rarely does one come across an artist who is so obviously indifferent to his work’s visual representation. West of the Jordan River, despite being aesthetically simplistic, is a documentary of astounding complexity and force. Not only does it encompass the efforts and failures to end the Israel-Palestine perpetual struggle, but it captures the political and social attitudes of Palestinian and Israeli populace with the level of detail unfamiliar to mainstream media.

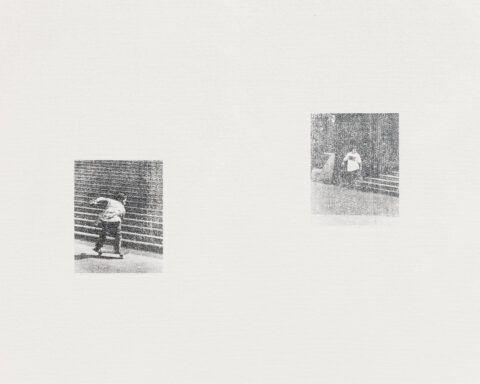

In Gitai’s interview with Rabin in 1994, the former prime minister says, “we must first make intermediate steps which would bring, by their success, evidence that peaceful coexistence is possible.” Gitai exemplifies Rabin’s objectives by ending his film at the backgammon tournament between Israelis and Palestinians. This peaceful and joyful event shows both people sharing the same culture and illustrates “the step” that people take towards reaching agreement and achieving unity. Ending his generally somber film on such an amiable note isn’t idealistic, but is realistic and pragmatic as it echoes the region’s existing and poised longing for tolerance.