“It was a gift of intimacy,” says The Eternal Memory director Maite Alberdi. The Chilean filmmaker’s reflection may be the kindest words ever spoken about the COVID-19 pandemic. The film observes long-time couple Paulina Urrutia and Augusto Góngora as the latter’s condition worsens due to Alzheimer’s. Paulina, meanwhile, indefatigably shoulders him as caregiver. However, The Eternal Memory also puts Paulina in the role of documentarian when COVID-19 lockdowns mean that Alberdi can’t be physically present to record their daily interactions. When the world shuts down, the film gains even more access to the couple’s lives as Paulina brings the camera into personal spaces, like the bedroom or shower, that Alberdi might not have been able to enter. This unfiltered view gains even more moments of candour as Augusto’s health declines during lockdown and keeps rolling.

The Eternal Memory hits theatres after winning the Grand Jury Prize for World Cinema Documentary at Sundance earlier this year and scoring the only notable doc sale at the festival with MTV Documentary Films picking it up for the USA (and The Impact Series in Canada). It might seem like an odd choice for the Sundance’s breakout doc: a small-scale film that brings fresh images of social isolation. However, Alberdi finds moments of revelatory compassion and love thanks to the challenges forced upon the shoot by the pandemic. It’s a devastating love story of the highest order.

Alberdi, who observed Paulina and Augusto over four years, says that the consistency of the bond between them held strong. “I felt the same emotion and desire over the years,” Alberdi observes. “In spite of [Augusto’s] deterioration and how he changed, the feeling never changed. Their lives and their love was the same from the beginning until he passed away.”

Following The Mole Agent

The Eternal Memory’s portrait of care marks a natural follow-up to Alberdi’s 2020 doc The Mole Agent. The film, which scored an Oscar nomination for Best Documentary Feature, observes the state of elderly patients in long-term care through the eyes of a shrewdly placed detective. Alberdi says it’s mostly coincidental that one film follows the other. “I think that all films prepare you for the next one,” notes Alberdi.

However, the director says Paulina’s devotion offered a striking contrast to The Mole Agent’s heartbreaking images of senior residents neglected and alone. “Her mind was completely the opposite of what I saw in The Mole Agent,” notes Alberdi. “Before the lockdown, she really tried to push Augusto into society, to bring him to work, and to not be isolated. That was surprising because I saw so many people with dementia completely isolated, but, in this case, she was trying to make him part of society.” The film sees Paulina, an actress and former politician who held the inaugural cabinet position for Minister of Culture, bring Augusto, a former political journalist and writer, to her classes where she teaches drama. Paulina often integrates Augusto into her lessons. She encourages him to be an active observer. This engagement makes the dramatic turn of the lockdown doubly poignant.

“The lockdown didn’t allow that push for them,” sighs Alberdi. “You see how, in the lockdown, Augusto deteriorated [as much] in one year what he deteriorated over many years. It’s a good example to understand how important it is for people with dementia to socialize. He had 10 years with Alzheimer’s, socializing in Paulina’s life, and had a good living until the lockdown. Seeing all the people abandoned and alone in The Mole Agent was completely the opposite of what I saw in this relationship.”

Navigating Consent and Consciousness

While Augusto’s condition declines during the production, Alberdi remains cognizant of consent. The director says that Augusto’s background as a journalist motivated him to share his vulnerability. “At the beginning, he was very clear that he wanted to show his fragility. He was very clear that he shot so many people experiencing pain and fragility,” Alberdi explains. “He said, ‘Why am I not going to open the door to my house if so many people opened the door for me to?’”

Alberdi says that Augusto entrusted her with a documentarian’s judgement when it came to filming, a responsibility that evolved over time as he condition changed. “As a filmmaker, you have to make your own limits and understand the question of the limits for each film. That is tricky because there are a lot of discussion about limits and ethics in documentary,” notes Alberdi. “There is no one answer for all films, or for documentaries in general. It’s an understanding of each person and each situation. You have to understand how to work together.”

For Alberdi, the question of when to stop filming, or when to end the story, proved the biggest challenge of production. “I wanted to be with them until the end,” admits Alberdi. “I wanted to be with them for 10 years, 15 years, 20 years, but the end is an abstract. The end [of shooting], for me, was the moment in the film when Augusto says, ‘I’m not anymore.’ He’s saying, ‘I’m not the person that I used to be anymore.’ That was the clear ending because I didn’t feel comfortable in that moment as a filmmaker. It was the first time that happened to me.”

Reconstructing Memory

There are some brutally tough moments in The Eternal Memory. One scene, for example, sees Paulina’s composure crack when she tells Augusto of an episode in which he failed to recognize her. It’s a disarming scene, naked in its raw emotion. Augusto comforts Paulina with no recollection of the slip of memory. The exchange might make viewers uncomfortable, but this candid moment happens during lockdown. Paulina is the one filming here and she uses the painful moment to engage her husband’s mental faculties. Similarly, The Eternal Memory observes Augusto’s deterioration during isolation when he breaks down with worry that all his books are gone.

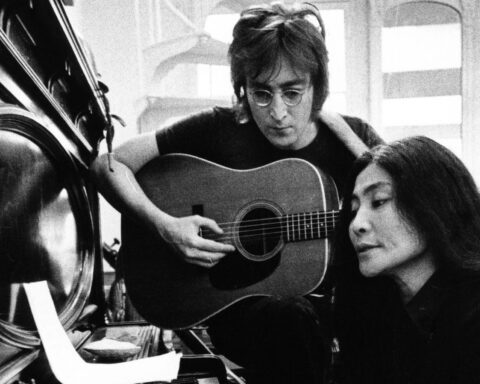

The film also shows Augusto at his best as Alberdi draws upon the journalist’s work and philosophy. Archival footage weaves throughout The Eternal Memory to illustrate Augusto’s role as a truth-teller for Chile’s people. His fearless reportage chronicles the violence of the 1973 coup. Archival images show citizens rallying in the streets when Augusto’s colleagues are assassinated for breaking stories about the violence of Pinochet’s regime. Besides honouring Augusto’s contribution to Chile’s collective memory, these images illustrate his deep understanding for the complexity of images and the risk entailed with trusting another person with one’s story.

“They were my co-creators…It’s a collective register where the three of us are telling the story.”

– Maite Alberdi

Preservation and Co-Creating

Archival images also show the younger Augusto imparting the practice of reconstructing memory. “Both of them worked to construct a collective memory in their careers,” says Alberdi. “He was concerned about making a register of history and telling everybody what was happening in the country. To tell is a way to preserve.”

Alberdi says everything clicked with the archives when she encountered footage of Augusto talking about one of his books and emotional memory. “I started [the film] wanting to make a love story, but I had to take care of his obsession for the topic of memory and his legacy of remembering.” The irony of Augusto losing his memories to Alzheimer’s adds to the film’s emotional complexity, but Alberdi also keeps his work alive by reconstructing these images that capture his role as an archivist of his people’s history.

“They were my co-creators,” observes Alberdi. “Paulina shot for two years and Augusto is the one who shot 20 years ago what you see in the archives. It’s a collective register where the three of us are telling the story.”

Paulina’s Voice

The film gets Paulina’s voice through the present material, another benefit of Alberdi entrusting her participant to play the filmmaker. “For me, it was important to tell about her past and her background because she’s a famous and important person in Chile,” Alberdi explains. “She decided to step out of her career and dedicate many years to taking care of Augusto. For me, that breaks the prejudice we have of which people take care of others.”

However, since Paulina was eventually tasked with recording Augusto, Alberdi says that finding her perspective was sometimes challenging, even though they corresponded throughout lockdown. “At one point, I wanted to put voiceover of her. I wrote a script with audio messages that she sent me during the lockdown to construct her voice,” notes Alberdi. “But her voice was super clear in the material that she sent me. She has moments where she expresses her fears.” Paulina’s strength resounds clearly through ther commitment to the project. While the emotional and physical toll is evident, Paulina’s role as the recorder affords the doc some deeply humane insight into the life of a caregiver. In some moments, she forgets that the camera is still recording and goes about her business. All she can do is sing to herself to keep from feeling alone.

Love Never Fades

In observing Paulina’s selfless love and Augusto’s desire to hold onto his memories of their relationship, Alberdi says that making the film was a lesson in the many forms that love takes. “They taught me that there is no one way to love and no one way to be a couple,” says Alberdi. “You can still enjoy your relationship in the middle of problems or illness and be a couple until the end.”

The film itself endures as an act of emotional memory as it carries on Augusto’s story. The journalist passed away on May 19, 2023 at the age of 71. While Alberdi says that Augusto ultimately wasn’t able to see The Eternal Memory due to his condition, sharing the film proves therapeutic.

“For Paulina, it has been very difficult to adapt to her new life because she was with him for more than 20 years and she was in that house for many years. But in a way, the film is helping her in mourning because she’s travelling with me now,” notes Alberdi. “It’s an opportunity to speak about him. When someone you love passes away, people often avoid speaking to you about that. In this case, it’s the opposite. She has the opportunity to speak about him, to speak about the relationship, so I think it has been a good way to live with it.”