Normally when declarations get made like “the hardest working man in showbiz,” it is just hyperbole for marketing purposes but when applied to Bruce Springsteen, one has to smile, because he is a rock iconic who has a reputation for performing a solid two hours without an opening act. The other remarkable thing is musical groups are lucky to last a week together while the E Street Band has largely remained intact since 1972 with the exception of saxophonist Clarence Clemons (replaced by his nephew Jake Clemons) and keyboardist Danny Federici. The death of his two bandmates combined with realization of being the last surviving member of his first group, the Castiles, has had a profound effect on the Bard of Asbury Park.

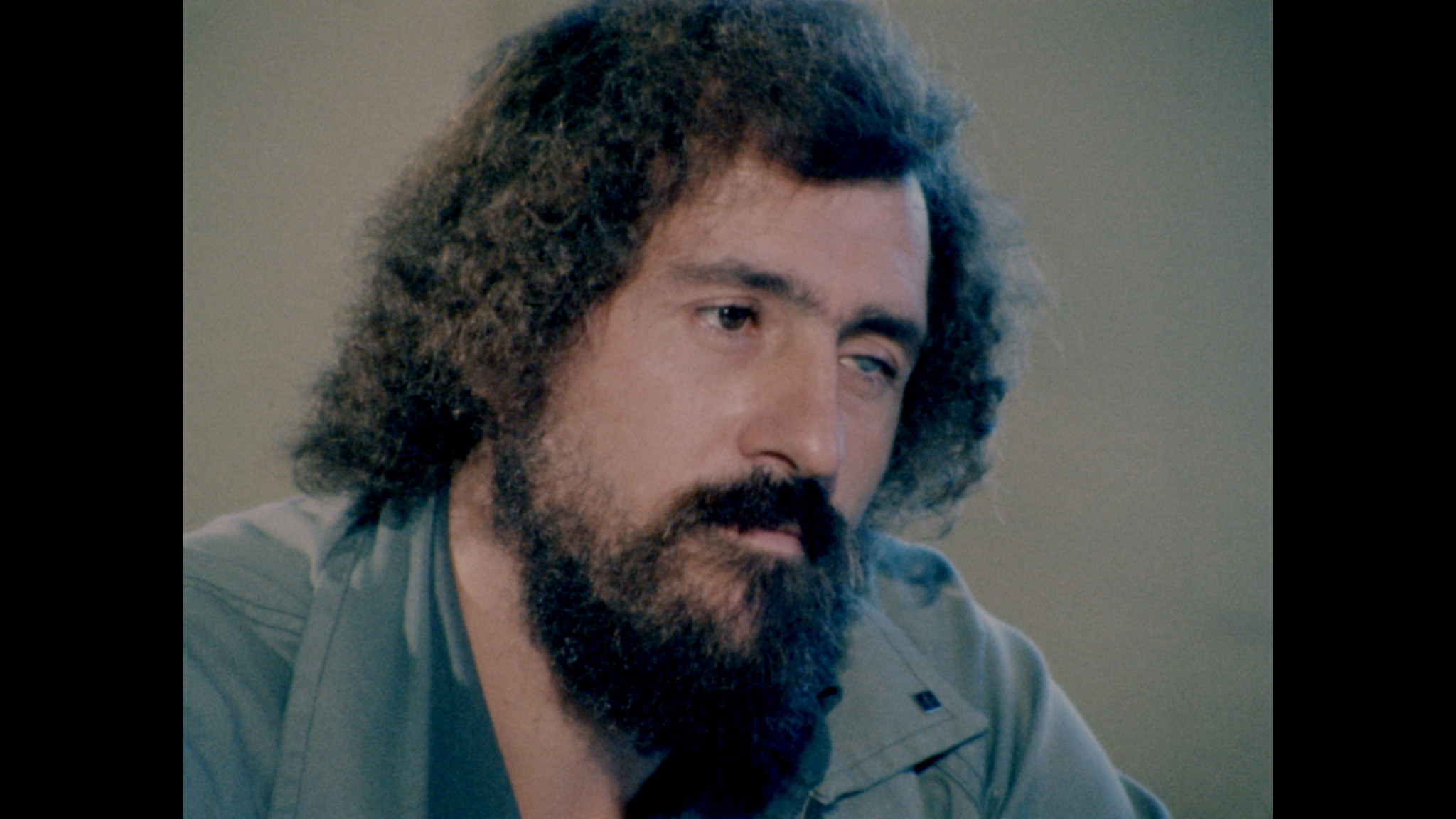

For the first time since Born in the U.S.A., Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band have recorded live a studio album with Letter to You — and it is an ode to the dearly departed. Capturing the five-day recording sessions was filmmaker Thom Zimny (Western Stars), who has been collaborating with Springsteen on music videos and documentaries for the past 20 years. Bruce Springsteen’s Letter to You streams on Apple TV+ and includes archival footage and narration from Springsteen in which he explains the inspirations for his songs as well as the wisdom gathered over the course of 71 years. It is strange thinking of the musician as an elder statesman since his youthful enthusiasm has not diminished since picking up a guitar and going on stage as a 16-year-old.

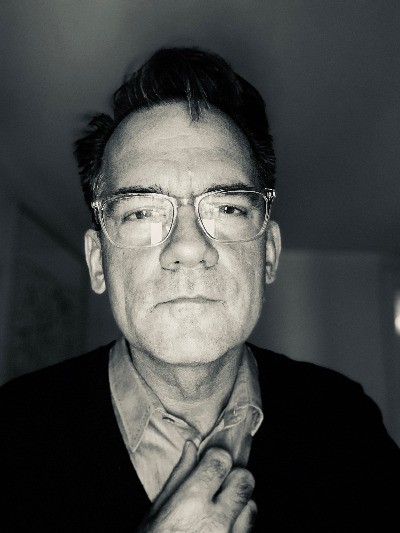

Zimny spoke to POV about being part of an inner circle, his approach towards documentary filmmaking, and the unwavering appeal of the music created by Bruce Springsteen.

POV: Trevor Hogg

TZ: Thom Zimny

POV: How did you go from being a fan of Bruce Springsteen to a member of his inner circle?

TZ: My journey to becoming a filmmaker and collaborator is one of luck. I got an invitation to edit with Bruce on a concert that became the TV special Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band: Live in New York City [2001]. I was at the right place and knew the music. The big thing was that I had a connection with him and Jon Landau [Springsteen’s long time manager/producer]. We reviewed the way that the music was being affected by HD [High Definition]. Back in the day, it was something that we were trying to figure out. It was too clear and taking away from the music. Right from the start we connected because the music was the focus, and I loved having the opportunity to step outside of being a fan and to trying to collaborate with him. That has been going for the past 20 years.

POV: There is a danger in meeting one’s idols in that they can be a disappointment.

TZ: My primary connection with Bruce is to connect to the artistry of his work, the lyrics and writing. I don’t take him to that place of icon/celebrity. I’ve always been interested in the journey of a working artist. I’ve always connected to Bruce beyond fandom. The body of work that he had, and also the power of his writing and storytelling complemented my interest in film and storytelling. Bruce’s music is cinematic. Before I worked with him, I would edit and sketch with his music. It’s one of those beautiful blessings where I’ve been able to collaborate with the man himself but my expectations of him never came from a place of fandom. It was more like I was hoping to be able to work with a great artist.

POV: What keeps you coming back to do more Bruce Springsteen documentaries? And what does Letter to You contribute to the ongoing conversation about him?

TZ: What keeps me coming back is the simple idea that every one of these projects is different, whether we’re making a music video and trying to convey a certain idea or point of view or a long form documentary, where we’re trying to tell the story of “Darkness on the Edge of Town” or the recording of “Born to Run” or “The River.” All of these stories have their own unique journey and show the results of his work with the band and as a person as well as his development as a writer. Every time he calls me, I’m totally surprised by which way we’re going. The last project before Letter to You was Western Stars, which was taking an album that was non-tour and making a live concert in a barn. That brought on its own challenges. Over the past 20 years I feel like we’ve never repeated ourselves. We’ve been in this zone of trying to tell a story and convey the power of the experience of the music. I try to stay in sync with how the music makes me feel. Letter to You tells a unique journey of both the history of E Street, Bruce’s relationship to his own maturing, and his journey as an artist. The beautiful side of it is that first connection of rock music in the Castiles, where you get a sense of how these guys grew-up in the clubs and the power that experience had for all of them.

POV: How did you get the right tone for Letter for You as it is both melancholy and a celebration of a life lived?

TZ: It wasn’t difficult to find the beauty and light in this film even though we’re looking back and there are moments that might be understood as nostalgic or mourning. The sheer presence of these guys and the energy of them creating was a pure light. I tried to symbolize that in the studio by showing the power of the presence of this place. Much like the chorus of “Ghosts,” these are guys who are alive and in the moment. They’re at the height of their powers in the studio. It wasn’t a group of men who no longer could do it. It was a celebration and in some ways for me as a filmmaker, it was watching a masterclass. They walked in and made this album in five days.

POV: With Bruce Springsteen being so involved in the production of Letter to You, how did you make sure that a documentary rather than a commercial was being made?

TZ: The idea of what classifies as a documentary is so open for me as a filmmaker. I don’t have a set of rules. When I look at Letter to You, it’s a mixture of languages. There are instances of cinéma verité in the studio and more controlled moments of shooting the score and written narration. Whether or not it’s a commercial, I had no direction from the record company or no limitations put on me by Bruce outside of, ‘Don’t get in the way of the recording.’ And, ‘Be there every day that you want.’ I had a freedom in making this film. It does reflect something that’s out there in the commercial world but it is by no means the ‘behind-the-scenes’ to sell the record. If it was just that then we wouldn’t be exploring the language of this kind of filmmaking. Bruce’s voiceover narration is far deeper than something that is trying to sell a product.

POV: Was it always intended to have Bruce Springsteen do the narration and was there a script?

TZ: There was no script. There was nothing but the experience of working with Bruce long distance through Facetime, and the beauty of texts and emails. We would respond to each other. I would send him footage of an aerial of snow and he would come back with a voiceover; as I would start to sketch to it, he’d send me a demo of what the score might be and I would work on the picture again; he’d enhance that, and I would change it again. That’s the back and forth and the language. The film and the editing of it was an organic conversation. There was not a game plan that we’re going to sell these songs. At no point was it even discussed as a film until it was done. I’ve worked with him this way for the past 20 years on the documentaries, in particular Western Stars where we spent time working on narration. The beauty of the narration is that it gives him this moment to expand on the scenes and some of the writing and characters in a way that goes beyond just a sound bite and an interview moment. In some ways it’s revisiting the record.

POV: It is fascinating to see and hear the rock icon interpreting “If I was a Priest,” “Janey Needs a Shooter” (co-written with Warren Zevon), and “Song for Orphans” which he wrote as an up and coming musician. What was it like capturing those moments and was the vibe in the studio any different compared to the other songs?

TZ: My memories of recording the two songs from the 1970s, “If I was a Priest” and “Song for Orphans,” was that the excitement in the studio was at an all-time high because the tracks were part of the start of Bruce’s career. Everyone was responding to the power of these very different lyrics and hidden away gems unfolding in the studio. There was a beauty to those sessions that I felt I had captured with the keyboardist Charles Giordano and the guitar sound. They had a wonderful nod to Dylan. Bruce sums it up great with the voiceover. Steven Van Zandt improvised a guitar solo at the end of “If I was a Priest” that I was so glad that my cameras caught and is one of the highlights of the sessions.

POV: It does make one wonder what the career path would have been like if Bruce Springsteen hadn’t veered away from the Dylanesque sound displayed by “Song of Orphans.”

TZ: I look at it from the point of view of an artist finding his voice. These songs reflect a use of language that gets honed in by the time you get to “Darkness on the Edge of Town.” All of it I find to be interesting. I never go back to a particular chapter and want the music to be that certain way. The stripped down quality of “Darkness on the Edge of Town” or the layered quality of “Born to Run,” those are all chapters that I find to be interesting as a music fan. They are very different and it is not different for me when I think about the Dylan influences over the early tracks. I can enjoy them but I also don’t define Bruce in my head as having to carry just one voice.

POV: Was it always part of the plan to have the winter aerials as scene transitions?

TZ: The language of the drones was to convey a sense of higher power. It came to me when I was listening to the lyrics being sung in the studio. I wanted to have this moment where if you are grounded in the environment of the studio, you feel like a character but I also wanted to take you out of that world. It had to be a world that had a God point of view. It was a lot of work to find the landscape that lent itself to the emotional tone of the voiceover. I looked at it as a character in the film. The character that steps in and lets Bruce have these thoughts as well as falls in sync with the emotional content of the score and narration, and doesn’t interrupt the flow of listening to him. There is a beauty in the drones that gives you the opportunity not to edit and just to experience. That’s what happened to me when I watched the drone footage.

POV: Were you capturing the footage in colour with the ARRI ALEXA Mini cameras and converting it to black and white?

TZ: We shot it in colour but I looked at everything in black and white from day one. All of my monitors were set with a colourist outside of the studio at a separate location who could bring in a visual tone.

POV: What was the reasoning behind the documentary being in black and white?

POV: What was the reasoning behind the documentary being in black and white?

TZ: The first time Bruce talked to me about the project, he was sitting outside and making a fire. It was a grey New Jersey day. He talked about the guys coming back to record for a week and said, ‘Lets film it.’ I got the idea for black and white looking across at the grey New Jersey sky and listening to the music. I thought to myself this should be in black and white, and the memories should be in colour. That’s what I ran with. It ended up being a powerful thing because I used snow as this visual metaphor for time and a spiritual quality for the music. All of those things read powerfully with black and white.

POV: Was there any discussion about making the archive footage black and white?

TZ: I love the idea of taking the viewer out of one world and putting them in another world. The brightness and clarity of the colours of Super 8 was a powerful transition. I loved establishing the world of the studio with black and white light.

POV: How did you go about devising the shot list for the three cameras to avoid interrupting the recording sessions?

TZ: There is not a storyboard outside of some general ideas of where we can stand without being in people’s way. It’s being in the moment, jumping around, and listening to the sonic details to make sure that we have the footage of that riff. You have the footage of Bruce saying, ‘I want you to do this and that.’ And then cut to a reaction.

POV: Did you see what was captured on one take and fill in the gaps with the next one?

TZ: That’s it but you also have to change up per song in the moment. You don’t want to repeat the language. I love to dirty the frame, play with the composition and capture the expression of eyes because the eyes drive the edit. That comes from my work on The Wire cutting dialogue scenes. I was able to work with some great directors and writers like David Simon. [I would take advantage of] any chance of pushing the edit in a certain direction where motivation was coming from people’s communication by small gestures and their eyes.

POV: I enjoy the shots of the E Street Band members taking notes when Springsteen presents a song to them because it gives you a sense of the creative process. Do you have any favourite moments like that?

TZ: I love that you referenced the notes. My favourite moments are the band communicating in what I call ‘the secret language.’ You see them scribbling away with pencils on notepads and 30 seconds later, they’re creating this magic as the E Street Band. My other favourite moment was watching Jon Landau become emotional during playback. Nothing was rehearsed with the cameras or told to do over again. It just unfolded and was an emotional outburst that symbolised to me how deep their relationship and collaboration has been over the years.

POV: How hard was it to find and incorporate the archive footage?

TZ: The archival footage is accessible to me but it’s hard to figure out what captures a young Bruce Springsteen when he is talking about the early part of his career. What’s the gesture that reads [well to an audience]? None of it is b-reel. All of it is storytelling to me. I’ll spend a lot of time trying to figure out, ‘What is the best shot that conveys this idea?’ What’s the best shot that shows Danny Federici and Clarence Clemons together onstage in one moment? What’s the best shot that can tell the story?

POV: How did you go about choosing the lenses and deciding upon the lighting schemes?

TZ: I have been blessed with the collaboration and friendship of [cinematographer] Joe DeSalvo who worked with me on getting vintage lenses that would flare. The light would pour into the studio and create these flares that worked with the landscape of keyboards and guitars. We tried to find the essence of this place as a character. Joe’s work with the drones is extraordinary because he understands the power of the composition.

POV: How hard was it to get the right pacing for Letter to You and is there much in the way of outtakes?

TZ: There is tremendous amount in the way of outtakes because I shot for five days. But the tonal quality of this film came from the simple moments that arrived when I got Bruce’s first voiceover. What he did was count off, ‘One, two, three, four…’. In that I heard the pacing of the film. That was the first edit that I made. I included that count off to start Letter to You. In many ways it set the tempo of what I would cut to, and how I would tell the story. I wanted it to feel like Bruce was writing this letter as the film unfolded.

POV: How did you approach the sound and go about incorporating the music into the narrative?

TZ: I looked at the sound and wanted different levels of textures. There is the documentary mode where you hear the grunginess of the guitar being played in the room and then there is the dialogue and background sound. I worked with Kevin O’Connell [re-recording mixer] to present the feeling of the environment [adding] a little bit of chaos in the sound. There are voices, which come from all of these places. I worked hard to make these different worlds come forward. The quality of Bob Clearmountain’s mixes are tremendous and bring sonically such power and force. We also mixed the picture so it’s not like I’m taking the stereo or surround mix and just layering it over the picture. I’m enhancing the mix as the picture unfolds. It’s a traditional mix picture environment but I look at sound as an important level to dissect. The studio is a character so it has to have its own sonic space. The same thing with the music when it comes out of the studio when the band plays. Where I cut to and how the drums fill in the moment, are big decisions to me when mixing the film. I’m obsessed with the beauty of the dirty and rougher sound but then also conveying the sonic qualities of the score, and varying in ambience and sound effects to heighten some of the voiceover and emotions of the tracks in the pieces between the songs.

POV: Where do you go from here with your relationship with Bruce Springsteen as a documentarian?

TZ: My big thing working with Bruce is that I never expect the next step to be an extension of what we just did. I’m ready for the next moment. I don’t know what that is going to be and that makes it exciting. I didn’t know about this until a couple of weeks before it happened. Bruce is always working and recording. I hope to keep collaborating with him and telling stories.

Bruce Springsteen’s Letter to You is now available on AppleTV+.