Jeronimo

(USA/Cuba/Korea, 100 min.)

Dir. Joseph Juhn

A personal holiday inspires a collective portrait in Joseph Juhn’s Jeronimo. The adventure begins when the filmmaker, a second-generation Korean American, embarks on a trip to Cuba. He lands in the small Latin-American island, eager to soak up the sun and get some R&R, but is immediately struck by the presence of his taxi driver, the first person he sees upon leaving the airport. She’s Korean.

The driver, Patricia, explains to Juhn that she’s a third-generation Korean-Cuban. Juhn benefits greatly from Patricia’s gift for gab and soaks up her family history as she tours him through the sunny countryside of Cuba. Patricia informs him that Cuba is a little known haven of the Korean diaspora, but one that features a very complex and intricate history. This history also happens to be intimately connected to Patricia’s family.

All roads lead to Patricia’s father, Jerónimo Lim (born Eun-jo Lim Kim). Although her father has long since passed, he left behind a large family and an impressive legacy that Patricia readily shares with Juhn. Camera in hand, Juhn meets Jerónimo’s wife, siblings, and children. They piece together the story of a remarkable life as well as an oral history of the Korean diaspora in Cuba.

The stories, which include perspectives from academics and members of the Korean diaspora both in Cuba and elsewhere, outline an overlooked history of migrants caught between worlds. It’s also a story of slavery as interviewees note how the first Koreans to land in the Americas, including Jerónimo and his family, were indentured to harsh physical labour in Mexico where they were sold to plantations and forced to work off their debts in the fields.

But the history of the Korean diaspora, and Jerónimo’s story specifically, differs from other tales thanks to the complicated political history of Korea itself. Juhn outlines how the Japanese occupation of Korea left migrants homeless once they were able to leave the plantations. At this point, the speakers tell Juhn how the families turned to Cuba, something of a natural neutral state in the occupation years, but one that also aligned with values liberated by the hardships of their travels. In the post-war years, interviewees describe their families feeling betrayed and becoming stateless again with the division of Korea. The Korean-Cuban experience is thus one of frequently questioning one’s place in the world.

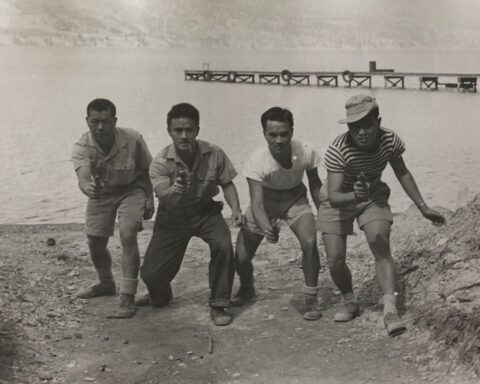

Lim’s family explains to Juhn how Jerónimo flourished in Cuba. Archival pictures and rare voice recordings help tell the story of a man who became the first Korean-Cuban to enroll in university. Even better, Juhn learns that one member of Lim’s cohort was Fidel Castro. Jeronimo offers a portrait of this strong family man who enjoyed a long career as a deeply committed member of the Revolution, working in the Ministry of Industry and befriending Che Guevara. The interviewees tell how each of Lim’s personal advancements took step forward for their community in Cuba.

Over the course of the three-year production, Juhn learns how Lim ultimately saw himself as a Cuban first and foremost while furthering the causes of Koreans on the island. Among the significant feats in Lim’s legacy is his effort to produce the first census of Korean-Cubans in the nation—no easy feat to accomplish, as the interviewees explain proudly to Juhn. Although the extensive recollection of both the Lim family and Korea’s complicated history in the twentieth century inevitably makes the doc somewhat expository, Juhn deftly connects the personal with the political. It raises necessary questions of identity and belonging, as well as the importance of keeping cultural history alive for generations to come.

Jeronimo reminds audiences that anyone is capable of enjoying a remarkable life regardless of who they are or where they find themselves in the world. Juhn’s collage of touching interviews with Lim’s family members speaks to the generations of people inspired by their ancestor’s dedication to leave a mark on their world for himself and his family. But there’s also an important essay on diversity and inclusion to be found in Jeronimo as we learn more about this man whose worldview and activism encouraged an exchange of values and perspectives between communities. It’s a tale both specific and universal.

Jeronimo screens at Reel Asian on November 10 at 2:30 pm at TIFF Lightbox.