Operation Varsity Blues: The College Admissions Scandal

(USA, 100 min.)

Dir. Chris Smith

Parents will do anything for their children. Rich parents, however, can do even more. The different set of rules by which the wealthy play receives welcome scrutiny in Operation Varsity Blues: The College Admissions Scandal. This saga is the headline-making affair in which Hollywood celebrities, well-to-do executives, pizza heiresses, athletes, and other wealthy people bent the rules to give their privileged kids additional advantages through post-secondary education. Director Chris Smith (Jim & Andy) finds a novel approach to this already well-trodden story. Operation Varsity Blues deviates from the “Netflix formula” of true crime documentaries when audiences might feel fatigue after a year of bleary-eyed binge watching. (Smith also produced pandemic hit Tiger King.) The film takes a docudrama angle to explore the human elements in a story in which audiences already know many details. The result is somewhat inconsistent, yet a shrewd examination of the social forces that invite and enable crimes.

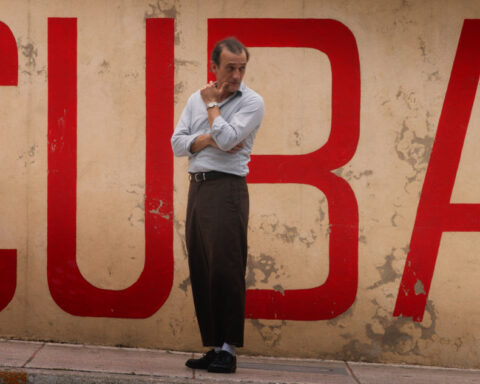

Perhaps one angle, simply, is the familiarity of the scandal. Operation Varsity Blues can’t tease a story out like some of Netflix’s true crime series have. (Murder among the Mormons, for example, was a predictable true crime Mad Libs exercise stretched across three episodes, padded and stuffed with slo-mo B-roll.) Blues moves quickly as it draws upon transcripts and recordings used in the operation that snagged the man at the centre of it, William “Rick” Singer, and the clients and coaches embroiled in the elaborate affair. Matthew Modine plays Singer and bears a striking resemblance to the wily huckster. He sells the docudrama conceit just as well as Singer peddles the true cost of education.

Blues recreates the machinery of a system driven by fraud and greed. Smith dramatizes conversations between Singer and the parents who doubled down on their kids’ futures and the university coaches and administrators who sold out for a quick buck. In doing so, Blues probes the dynamics of power and control that not only enable fraud, but also reward it. The scheme is a fascinating operation.

Singer and several of the participants who appear in conventional talking heads interviews (mostly third parties and not people directly involved in the racket) explain that the privatised and elitist nature of college admissions invited this fraud. Blues explains how college has three doors for entry. There’s the front door, by which students enter with a conventional application, perhaps a scholarship or extracurricular merits, and crossed fingers. The back door, on the other hand, opens when parents make a generous donation with hopes that their kid’s application receives a second look. However, parties in Blues note that a donation brings no guarantee. One of Singer’s clients, for example, gave a university one million dollars and his kid still didn’t get in!

The high-cost gambles of the front door and back door open what Singer calls the side door. This option comes at a lower price—a few hundred thousand—and Singer guarantees acceptance. Parents pay for kids to gain admission via recommendation from the athletic scouts, who’ve reserved some spots after Singer greased their palms or won their trust. Then they fake some photos and build a narrative to support the coach’s endorsement.

Entering through the side door opens a field of systemic inequity. The interviews and re-enactments, nearly all of which appear in cavernous mansions or swanky hotels, illustrate how Singer’s shady practice benefits only kids who already have the upper hand. These are parents with money to burn. Moreover, Blues lets the experts unpack the growing cottage industry of college elitism by which schools are deemed more prestigious by arbitrary merits, and then admission becomes more competitive and expensive. Parents who can pay for SAT coaches and costly tutors can groom their kids for admission at an elitist school, while working class or low-income families settle for “lower” end schools that don’t bring the same warped career prospects.

Smith’s film also looks at the dynamic of necessity created by privatised college. The coaches explain how they are also fundraisers. They are also bound by a system that favours the rich, as coaches who can procure money easily can devote more time to coaching, or have more work/life balance. The film shows how Singer’s operation favoured fringe athletics, like sailing or rowing, that don’t have ticketed events and therefore lose money by design. The coaches need private donations, and the sports generally cater to kids from affluent backgrounds. Singer, via Modine, convinces all parties it’s a win-win situation.

While Singer is the guide through which Operation Varsity Blues explores the scandal, it enters the lives of the involved families. Smith introduces the case of Olivia Jade, daughter of actress Lori Loughlin and designer Mossimo Giuanuli, who got into USC through Singer’s shady process. The film features ample footage of Olivia Jade’s well-documented social life. As an Instagram influencer, she already had a sizable audience and relatively promising enterprise, as well as numerous videos in which she shared her dislike for school and desire to forgo college in favour of pursuing her brand. Her well-documented social life, moreover, tipped off her guidance counsellor that her alleged athleticism was merely a ruse. Smith shows through Jade’s story how the parents’ motivations are often self-serving, as if securing a prestigious education for their kids is merely further evidence of their status. Moreover, when the film examines many other kids, it shows how they probably would have been admitted to their college of choice on merit. Their parents simply doubted them.

The absence of Felicity Huffman is notable, and might disappoint film fans interested in one of the scandal’s biggest names. (And most surprising guilty parties.) The film’s writer/producer/editor Jon Karmen says in the film’s press notes that the production decided to forgo scenes that recreated Singer’s conversations with Huffman and Loughlin. The reasons cited are that it would be too strange to cast actors as the familiar stars, and that Karmen and Smith focused on scenes that were “the most dramatically interesting.” Both of those excuses ring false.

For one, Operation Varsity Blues openly signals its construction. One is already aware that one is watching actors like Modine interpreting a story. Similarly, the cases of Huffman/Loughlin have as much or as little juice as the other stories do. Like everyone else featured in the film, they simply used their privilege to give their kids additional advantages. However, unlike most of the other parents, they have true celebrity and name recognition that might have thrown extra weight with the colleges, thus making Singer’s services redundant. The omission of their stories therefore feels like of a cop out, as if Smith lets the Hollywood pair off the hook. (“Huffman”: https://www.netflix.com/browse/person/20015110 and Loughlin also have ample content in the Netflix catalogue, although the streamer allegedly dumped the latter from the fifth season of Fuller House.) Alternatively, the actors might have benefitted from humanising moments that unpacked their serious mistakes.

By focusing more on the intricacy of Singer’s operation and the implications of its duplicity, however, Operation Varsity Blues forgoes the salacious. This doc spins a highly entertaining and utterly captivating operation that is two-fold, illuminating the scandal and the investigation that snared the wealthy crooks. The film doesn’t make an argument for free post-secondary education, but it certainly invites it by illustrating how brazenly the current system rewards a powerful few.

Operation Varsity Blues is now streaming on Netflix.