“It’s the eyes,” she said. “We enter into a relationship through the eyes. I have a relationship with this person, and she’s responding to me, and the person viewing the photograph has then all kinds of things they can learn about that person.” This is how the immensely influential Quebecoise photographer and editor Denyse Gérin-Lajoie—a long-time friend and colleague with whom I exchanged letters about issues in documentary photography— described to me the essence of how she approached her work. If photography, at its most basic level, is about communication, then it is dependent on the ability of the photographer to not only penetrate into someone else’s world or culture, but to cultivate the human relationships that ensue.

In a recent interview, Fernanda Rodrigues, who works at the archive of Sesimbra, a small town in southern Portugal, that Gérin-Lajoie immortalized in her classic book Sesimbra uma vila piscatoría (2008), recalled how the photographer—foreigner and female—was able to easily open doors in a traditional fishing culture that is maleoriented. Tradition and superstition would not permit a woman to set foot on the boats, lest she be a portent of misfortune. But Gérin-Lajoie persevered, and with her warm heart, infectious smile, and respectful manner, she overcame local lore and won the admiration of the community. “Ela falava com la fotografia,” Rodrigues said. “She spoke through photography. I think it was easy for her because of her deep passion for the work of the fishermen. The fishermen felt the closeness that Denyse had for them.” And unlike male colleagues, Gérin-Lajoie also photographed the women: the wives, mothers and daughters of the fishermen as they worked in front of their homes mending nets, or participating in the religious procession of the fishermen’s patron saint, Senhor Jesus de Chagas. Working almost ten years on the project, she was inspired by the parallels between the fishermen of Quebec who plied the cold waters of the St. Lawrence River, and the fishermen of Sesimbra who for centuries ventured as far as the waters off Newfoundland, both in search of cod.

Gérin-Lajoie was born in 1929 in Montreal and died there in 2012. On both sides, she came from prominent upper-class families with deep roots in Quebec history. Her mother was a cousin of Jacques Parizeau, a Parti Québécois premier of Quebec, and her father was a professor of gynecology at the University of Montreal and a renowned doctor who became head of the World Medical Association. Her great-grandfather was un homme de lettres who authored “Un Canadien errant” (“A Wandering Canadian”), an 1842 song about the exiled Patriotes of the 1837-38 Lower Canada Rebellion. The song is so deeply entrenched in Quebec culture that it has attained the status of a patriotic anthem. It was made popular in English Canada after it was performed by Ian and Sylvia and Leonard Cohen.

Though raised in a privileged environment, Denyse’s socially conscious parents instilled in her a deep sense of altruism and social justice as well as an abiding love of the arts and literature. She wrote evocatively of how her father taught her to love the ways of the First Nations people, whom she first got to know through the young guides who accompanied the family on their annual fishing trips in the forests of northern Quebec. She said, “What I learned on these trips was the respect that my father had for the Other. The respect for someone else’s great knowledge of life in the woods and on the lakes. I have learned their extraordinary respect and love for nature. At noon, we would stop fishing in order to cook, on a fire made of small tree branches, the fishes caught in the morning. While eating seated on the sand around the fire, we formed, every one of us, a Oneness.”

These childhood experiences would later serve her well in her humanistic approach to documentary photography. Married at 19, Gérin-Lajoe had six children, with one dying as an infant. After twenty years of married life, she and her husband separated, and she renounced the comfortable life of an upper middle-class suburban housewife. It was 1969, and Quebec society was undergoing a radical transformation in the aftermath of the Quiet Revolution. The women’s liberation movement was also making great strides forward across Canada. The afterglow of Montreal as host to the world in Expo 67 would linger for a long time. In francophone Quebec, there was a feeling of great expectations as the nascent separatist movement transformed itself from a cultural concept into a powerful political force that would not only change Quebec, but alter the very nature of Canada as well.

To young, educated francophones like Denyse, it seemed that anything was possible. As a single parent, Gérin-Lajoe plunged into a professional career in the arts. Soon after, she met Jorge Guerra, a Portuguese photographer and filmmaker in exile from the Salazar regime, whom she would later marry and live with for the rest of her life. Together, they took over a fledgling art photography magazine published in Montreal, Le Magazine OVO, and nurtured it into a groundbreaking, influential publication of socially concerned photography in the 1970s and 80s. The magazine at first featured portfolios of emerging photographers from Quebec and elsewhere; it later focused on re-contextualizing the work of established photo artists from across Canada, exploring “politically challenging” themes of the day, such as immigration, prisons and women’s issues. Gérin-Lajoie and Guerra introduced international work to Canada, and OVO was the first in the country to publish photographers like Pedro Valtierra, from Mexico, and Pierre Gaudard, from France.

Particularly noteworthy was an entire issue dedicated to the Photo League, an organization that documented working class culture and life in New York in the 1940s and 50s, as well as a movement of politically-conscious photographers including figures like W. Eugene Smith, Walter Rosenblum, Arthur Rothstein, Aaron Siskind and Helen Levitt. The Photo League had been disbanded decades earlier as a result of pressures from McCarthyism in the United States, and had been forgotten in Canada, until OVO re-introduced it in its pages.

With a combined circulation of 5,000 copies in separate French and English editions, the “little” magazine set a high bar. OVO’s innovative approach to the usage of photography earned it critical attention in cities like New York, Paris, Milan and Prague. The magazine’s operations expanded to include Espace OVO, a combined research centre and art gallery in historic Old Montreal, and a limited program of book publishing.

Denyse and Jorge had by now become a formidable couple in the arts community in Montreal, but after 15 years of intense activity, the magazine had exhausted them. The editors’ insistence on using photography as the core element in political and cultural analysis of difficult issues, instead of traditional portfolios of photographers, created significant disgruntlement among some members of Quebec’s and Canada’s photographic communities. The resulting controversy affected the editors deeply, especially since many of the 300 photographers that they published had benefited from being in the pages of the magazine. Ultimately the magazine’s perennial financial difficulties forced it to close in 1987.

As editor and co-director of OVO, Gérin-Lajoie left a unique legacy in the annals of Canadian art. As the influential American critic A. D. Coleman wrote in Camera & Darkroom magazine in December 1993, “I can certainly attest to OVO’s value to those of us here in the States who were trying to overcome the U.S. tendency towards parochialism by keeping track of what was happening north of the border… [Its archive] is a unique repository; it may well be the most comprehensive source still intact and available of what was coming into Canada, coming out of Canada, and happening within Canada in photography during the project’s lifespan.” Coleman also noted that with the exception of the American publications Aperture and Afterimage, he knew of “no comparable project from that period whose operations presumably can be studied thoroughly from the original documents.”

With the demise of OVO, Denyse Gérin-Lajoie turned her attention to projects that she had interrupted long ago by the demands of her editorial duties. For the first time in her life she pursued a full-time freelance career as a documentary photographer and artist. Although she had been photographing since her teenage years, she held her first solo exhibition at age 60 at the Worcester Center for Crafts, Massachusetts. It was a retrospective of her life’s work, well received by the media, but more than that, she was thrilled that her six grandchildren attended the vernissage. “In most families,” she said, “it’s usually the grandparents who attend the solo exhibition of a grandchild, but in my case, it’s the grandchildren who came to support their grandmother artist.”

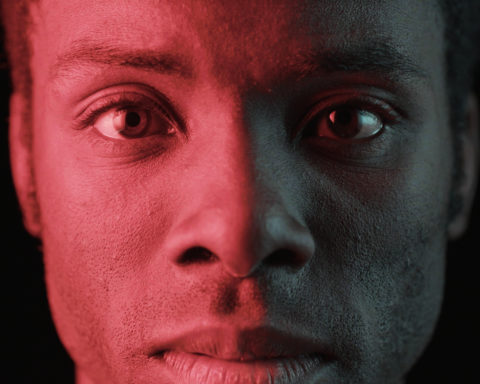

The exhibition included a unique series of portraits of artists and writers called Faces of Quebec. Using black and white film, and a classic 35mm Leica camera, her portraits are direct and probing, photographed in natural light, and almost always composed in a horizontal format, which is unexpectedly disquieting for a human face. In each there is an unmistakable relationship between the photographer and the subject. You cannot get away from the penetrating gaze which became a hallmark of her portraiture.

Profil de la vie, Gérin-Lajoie’s next major work, was a complex installation of 69 pieces of black and white portraits and interiors, colour Cibachrome prints of exteriors, and seven elaborate montages of portraits of her children and family members, each superimposed on the repeated image of a stark landscape of trees and water. It was an autobiographical piece in which she explored her maternal lineage, and a visually stunning tour de force that received critical acclaim, including in the celebrated journal Vie des Arts. Profil de la vie was, in her words, “tales of my encounters with people, places and objects… [a] love affair with life. Time and space, light and shade are so similar to joy and sadness, to resignation and to struggle, to tenderness and passion, that photography for me is a medium eminently suited to write one’s very story of love with life.” This work was exhibited later in Toronto, Montreal, Boston and Lisbon.

In 1990, Gérin-Lajoie established a permanent residence in Portugal, and together with Guerra, alternated between Lisbon and Montreal. Lisbon is a city of light and stone, with acres of white cobblestones virtually carpeting the entire historic city centre. The play of light bouncing off the randomly-shaped white stones gives the city a feeling of translucence, and makes it a visually inspiring setting for street photographers. Denyse explored her newly adopted city and embraced its culture passionately, producing an exhibition, Uma mulher na cidade, and also a book version which sadly remains unpublished.

Living between two worlds, she was as excited about Lisbon and Portugal as she was about Montreal and Quebec. She wanted to give back to hew newly adopted country, and in 1995 gave a handmade leather-bound album of 135 photographs of life in Sesimbra,to the town’s public library. She created the 68 by 48 cm album “in the spirit of family photo albums, which in the past could be found in many homes, as a way of saying thank you to the people of Sesimbra for their confidence in me, politeness, and patience during my innumerable photo incursions on their streets.”

This gift was followed by a larger donation in 2016 of over 1100 work prints of Sesimbra, plus some negatives, slides and other documents, by Guerra. For Gérin-Lajoie, it was also a question of giving back in the context of an artistic practice that is usually associated with “taking,” as the expression “taking a photograph” ruefully implies. But giving back implies far more than gifting prints to public institutions. “Giving back” in photography also has to do with the preservation of memory—of a way of life—and it is especially important in a town such as Sesimbra, where only twenty years after Gérin- Lajoie’s documentation, fishing has been surpassed by tourism as the main economic activity. Much of the town’s fishing culture that was its mainstay for centuries has now been relegated to memory, preserved in moments recorded by her photography. As Rodrigues states, “memory is the most important part of a culture of a people. If we don’t preserve the memory, we lose the sense of history and of collective identity. The picture is memory: a photographic image preserves the moment, but the memory of the photograph preserves the history of the community.”

Denyse Gérin-Lajoie’s legacy is more than the preservation of history and culture through photography. As one of the first photographers to explore family history and ancestors along maternal lines (with Profil de la vie), she broke new ground culturally and set the bar high for younger women artists. But she didn’t stop there: Denyse ventured beyond her home shores into unknown cultures and embraced them with such honesty and humility that her disarmingly simple photographs reveal, in fact, a form of humanism that she called Oneness with the Other. As a daughter of Quebec, Denyse Gérin-Lajoie demonstrated that going beyond the restrictions of birth and culture enriches the person and the art.